While visiting the Villa d'Este in 1913, Pierre S. du Pont, the founder of Longwood Gardens, announced, “It would be nice to have something like this at home.” This was a sentiment shared by other wealthy Americans visiting Europe around the same time. American residential landscape design in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—now known as the "Country Place Era"—was driven by these educated and well-traveled individuals who had the desire and means to build elaborate European-style estates at home. Mr. du Pont was developing Longwood Gardens not long after George Washington Vanderbilt II established the sprawling Biltmore Estate; at the same time, William Bowers Bourn II was constructing his country house, Filoli, and John D. Rockefeller was building this hilltop palace, Kykuit.

Longwood Gardens, like these other estates, borrowed heavily from French, Italian, and English designs. But rather than rely on a professional landscape architect, Pierre S. du Pont designed Longwood Gardens himself. With the help of his hand-picked staff of talented engineers, electricians, and gardeners, he carried his ideas to fruition, often improvising along the way. The Main Fountain Garden at Longwood Gardens is a unique example of the melding of several European design influences.

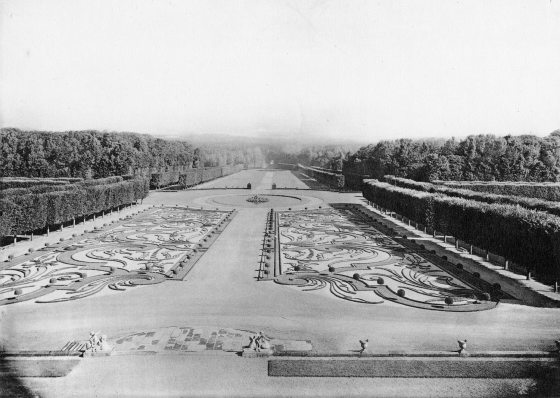

Champs, Le Parterre de Broderies, from Jardins de France by P. Pean, volumes 1 and 2, 1925. Note the manicured allées of trees, typical of French gardens of the time.

In overall concept, the Main Fountain Garden is more in the French style than any other. Its sprawling scale, symmetrical layout, and crisp allées of trees are all distinctly French. Mr. du Pont had viewed such allées throughout France, especially at Versailles and Champs-sur-Marne, although his main encounter with French gardens occurred several years after planting the 1921 allée in front of the recently built Conservatory. But what he especially noticed during his 1925 France trip was how a hillside could be walled and terraced to provide a fitting termination to a central vista, as well as to provide an elevated reservoir for gravity-fed fountains. Vaux-le-Vicomte and Pomponne were especially impressive, and at Vaux the central grotto is, at a distance, reminiscent of the central Loggia at Longwood. At Longwood, too, the hilltop reservoir was the starting point for the water’s journey through the Garden.

The grotto at Vaux-le-Vicomte, from Jardins de France by P. Pean, volumes 1 and 2, 1925.

If in overall layout the Main Fountains are French, the details come from the gardens of Italy. In 1910 and 1913, Mr. du Pont inspected the marvelous fountains in Italy that have inspired designers and writers for five centuries. The arched retaining walls on the east and south sides of the Main Fountain Garden bear a striking resemblance to the water theatre at the Villa Torlonia in Frascati. The spouting baskets, scuppers, and rose buds on the south side of the Upper Canal certainly were inspired by the Avenue of a Hundred Fountains at the Villa d’Este near Rome. And by hiring Italian stonecarvers to both design and carve tons of imported limestone, Pierre gave an authentic Italian stamp to the finished Main Fountain Garden. (Elsewhere at Longwood, direct inspiration came from the Villa Gori outside Siena, on which Longwood’s Open Air Theatre was based; and from the Villa Gamberaia outside Florence, which provided the plan for Longwood’s Italian Water Garden.)

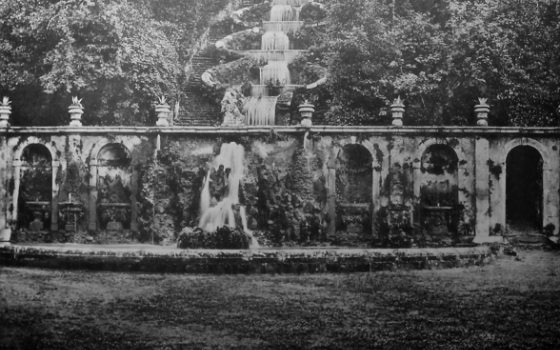

Arched retaining wall at the Villa Torlonia, from The Art of Garden Design in Italy by H. Inigo Triggs, 1906.

The terrace of fountains (Avenue of a Hundred Fountains) at Villa D’Este, from The Art of Garden Design in Italy by H. Inigo Triggs, 1906.

Just outside the formality of the Main Fountain Garden, visitors will find a landscape reminiscent of an English park. Mr. du Pont planted the hillside behind the fountains with towering trees arranged in an irregular, naturalistic way. This deep green, wooded vista provides a superb backdrop to the sparkling jets.

These European garden ancestors were enjoyed mostly by day, whereas Longwood’s fountains take on an entirely different aspect by night. Pierre noted that inspiration for colored water came from the fountains at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, one of many exhibitions he had the good fortune to attend. All touted the latest technology in the new Age of Electricity. Pierre S. du Pont was one of the first designers, and remains one of the best, to have combined Baroque sparkle with 20th-century technology. The result is something only he could have created.

The illuminated fountains at the World's Columbian Exposition, from The World's Fair in Water Colors by C. Graham, 1893