It may come as a surprise that Longwood Gardens has, in addition to its extensive plant collection, a number of important non-plant collections. Longwood’s Library and Information Services (LIS) is the custodian of an exciting compilation of artifacts, such as Mr. du Pont’s furniture, a Digital Gallery that currently holds 138,953 images of the Gardens from across the decades, and an extensive rare book collection, some of which belonged to Mr. du Pont. These items require curation and care from a team of dedicated librarians and archivists. In the spirit of this year's theme for A Longwood Christmas, we'd like to share a bit of history surrounding one rare book in our collection.

If you’ve visited the Gardens recently, you know that Longwood has taken flight this season with a stunning bird-inspired holiday display. What you may not know is that this area of Pennsylvania has a rich history in the study of ornithology, thanks to Alexander Wilson (1766–1813), a Scottish-born poet and activist who emigrated to America in 1794. In focusing on feathered embellishments and bird-related artisan crafts, Longwood’s holiday display celebrates an exciting element of our local history.

Wilson was born at a time when the Scottish were restless under English rule. His father distilled and smuggled whiskey in retaliation against English law and Wilson himself demonstrated a similar distrust of authority by becoming active in the unionization of weavers. Inspired by the great Scottish poet Robert Burns (1759–1796), Wilson wrote poetry in the Scottish dialect that was intended to expose the working conditions within local mills. The publication and circulation of his poetry caused Wilson to be arrested and imprisoned on three separate occasions between 1792 and 1794. In May 1794 at age 28, exasperated by a system he considered to be less than democratic, Wilson left Belfast on the vessel Swift and set sail for America.

Wilson disembarked the Swift in Wilmington, Delaware, and made his way to Philadelphia. In his first letter home he recounted the experience:

"As we passed through the woods on our way to Philadelphia, I did not observe one bird such as those in Scotland, but all much richer in colour. We saw great numbers of squirrels, snakes about a yard long, and some red birds."

Upon arriving in Philadelphia, Wilson took work as a school teacher; in 1802, while teaching at The Union School in what is now the Kingsessing neighborhood of Philadelphia, he met William Bartram (1739–1823), noted American naturalist and Kingsessing native. Bartram became a friend and a mentor to Wilson, instructing him in bird identification and supporting the development of his illustration skills. Wilson would put these skills to work in the creation of his periodical series, American Ornithology.

The Bartram family had lived on what is now known as Bartram’s Garden since 1728, when 102 acres were bought by plant explorer John Bartram (1699–1777), who used the land to cultivate the world’s largest collection of North American plants. John Bartram was also involved in the exchange of seeds and plants with Peter Collinson, a London based trader. His seed and plant business survived three generations of Bartrams; the house and garden are now open for public visitation.

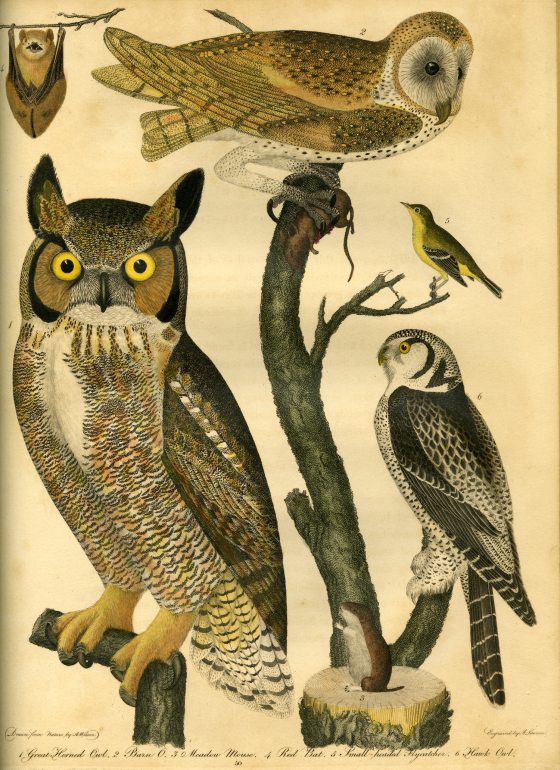

American Ornithology; or, the Natural History of the Birds of the United States: Illustrated with Plates Engraved and Colored from Original drawings taken from Nature (1808–1814, first edition) was published in seven volumes, all of which can be found in Longwood’s rare book collection. Wilson’s approach to the study of North American birds sets him apart from his contemporaries. At the time, the custom for the natural sciences was to create illustrations and descriptions from preserved specimens. However, the preservation process, even when carried out correctly, caused color deterioration in the specimen and provided little information about the natural behavior of birds. This led to inaccuracies in natural history texts and misunderstandings regarding bird identification, especially in species where males and females exhibit significantly different behavior or plumage.

Wilson, however, observed birds in the wild and made field drawings, providing access to a greater set of experiential data and true-to-life color and form. Furthermore, Wilson applied the Linnaeus Taxonomy (a scientific classification suggested by Carl Linnaeus in Systema Naturae, 1735) to the avian world, classifying birds by genus and species as Linneaus did for the plant world.

While field research for American Ornithology took place all over the United States, some work on the periodical itself took place right in the Bartram house, where Wilson studied when visiting from Philadelphia. Local Philadelphia engravers and colorists, including Anne (Nancy) Bartram, were employed to bring Wilson’s sketches to life, transforming his field drawings into stunning full-color prints, some editions of which were published in Philadelphia. These Philadelphia connections make American Ornithology a local as well as a national treasure!