In the remote flood plains of South America, a giant water lily blooms, attracts pollinator beetles, produces fruit and seed, and thus carries on through time. The discovery of Victoria regia, its world-wide cultivation, and the man-made works of beauty it inspired are the subjects of a new exhibit at Longwood Gardens entitled Secrets of Victoria: Water Lily Queen.

“The patience and skill of man has borne this magnificent plant from its native home, and transplanted it in the gardens of these northern regions.” So did Reverend John L. Russell refer to the persistence of explorers and horticulturists that led to the flowering of Victoria across continents and to its first New England bloom in Salem, Massachusetts in 1853. It blossomed in the greenhouse of John Fisk Allen, who documented the event along with Russell’s words of praise in the 1854 book, Victoria Regia; or The Great Water Lily of America.

A century later, Longwood’s first water lily grower, Patrick Nutt, would search for a copy of Allen’s rare folio to add to the library’s collection. Earlier, he had relied on an 1851 work by J.E. Planchon and L. Van Houtte, La Victoria Regia, to gain knowledge of the hand-pollination techniques he used to develop Victoria ‘Longwood Hybrid’ in 1961.

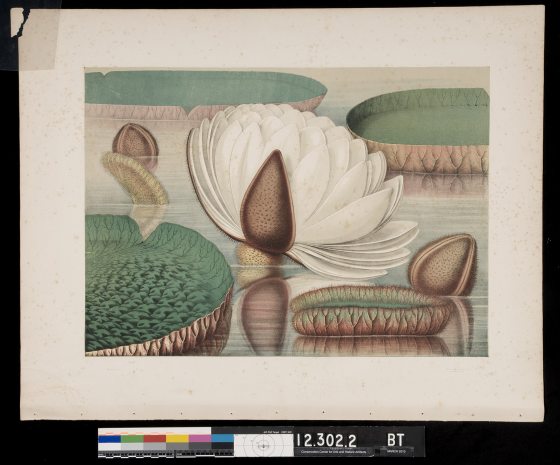

You can view both these works in the Music Room through September 29, but pay particular attention to the six life-size images of Victoria that grace the walls. On display for the first time at Longwood, these illustrations by William Sharp are the unbound plates from John Fisk Allen’s Victoria Regia, and are among the first and finest examples of American chromolithography. Like the water lily itself, you can admire the art for its quiet, sensual beauty. Look more closely, and you might discern clues not only to the life cycle of the plant, but also to the processes underlying the art.

Lithography is a method of printing based on a chemical fact: oil and water don’t mix. The artist draws with a greasy crayon on a flat stone, which is then covered with a thin film of water. Ink is attracted to the greasy image, but repelled by the water that fills the non-image areas. The resulting black-and-white prints were often colored by hand.

William Sharp of Boston was among the first U.S. printers to experiment with chromolithography, which builds layers of color in a print directly from the stone, requiring a separate stone and drawing for each color of ink. Look for the corner pinholes that were used to line up, or register, the paper for each successive printing. You might also detect the roughness of the stone underlying the image.

If you had seen these plates while they were still bound, you would have noticed discoloration and foxing—a type of spotting, from mold or metallic impurities, that affects old paper-based materials exposed to humidity. To prepare Sharp’s lithographs for display, Longwood entrusted the Fisk Allen folio to the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) in Philadelphia.

Gwenanne Edwards, who is a National Endowment for the Arts Fellow at CCAHA, described the painstaking process. First the book was unbound, spine adhesive was removed with a scalpel, non-image areas were surface-cleaned with a brush and grated erasers, and the pages were washed in calcium-enriched deionized water to reduce acidity and discoloration. Then, protected by plexiglass from harsh ultraviolet rays, the prints were bleached face-down under hydroponic lights.

Further treatment included localized chemical bleaching, mending of tears and support of binding holes with wheat starch paste and mulberry paper, humidification and flattening, and the final matting and framing. But along the way, the conservators took time to stop; to assess; to see what had worked; to discover what more was needed.

Cultivation, chromolithography, conservation. All involve a certain chemistry. All were developed by trial and error, through years of study and practice, requiring “the patience and skill of man.” All were touched by the beauty and wonder of Victoria.