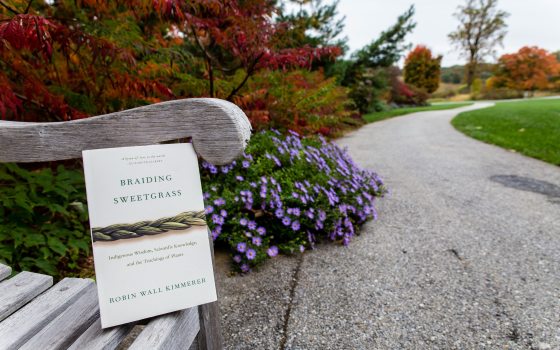

Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass.

"Plants are our oldest teachers," says Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass, Longwood's pick for our second annual Community Read. So we might, indeed, do well to listen as Dr. Kimmerer weaves tales of plant wisdom from strands of Native American knowledge, scientific research, and her own experience—both as a professor of Environmental Biology at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York; and as a student of the Potawatomi culture that is her heritage.

The author blends scientific and indigenous ways of knowing with a literary skill that engages mind, body, spirit, and emotion. Her passion for restoration, not only of plant communities significant to Native American culture, but also of our broken relationship with the land, will remind Community Readers of last year’s inaugural selection by Aldo Leopold, whose work influenced Kimmerer.

Through the use of story, Braiding Sweetgrass helps us remember things we already know—that the earth provides us with gifts, that with each gift comes responsibility. This idea is expressed by the Honorable Harvest, a traditional teaching that offers a modern pathway to sustainability. It "asks us to give back, in reciprocity, for what we have been given . . . through gratitude, through ceremony, through land stewardship, science, art, and in everyday acts of practical reverence."

"We are showered everyday with gifts, but they are not meant for us to keep … our work and our joy is to pass along the gift and to trust that what we put out into the universe will always come back." Photo by Daniel Traub.

Braiding Sweetgrass, which took seven years to write, was one of those acts of reverence. "Writing is an act of reciprocity with the world," says Kimmerer. "It is what I can give back for everything that has been given to me." Her gift for writing is considerable, and the power of her narrative voice pulls taut and smooth the braid of tales that comes together in Sweetgrass

We hear the creation story of Skywoman and the cautionary tale of Windigo as if intoned around a campfire; we hear the hopeful chatter of ethnobotany students as they go "swamp shopping" for materials to build a shelter; and we hear the whisperings of plants—the "more than human" voices that share our world—as they teach us how to live in reciprocity with the land.

From grass we learn that "the relationship between plants and humans must be one of balance . . . through reciprocity the gift is replenished. All of our flourishing is mutual." Photo by Carol DeGuiseppi.

In all times and cultures, it is the storytellers who relate the truths we need to hear, through characters that captivate and tales that inspire. The power of Kimmerer's stories, which hint at the hopes and duties inherent in our relationship with nature, is that they shake us awake, help us to remember, and make us care. After reading "Maple Sugar Moon," you will not soon forget why it takes forty gallons of sap to make a gallon of syrup. And although science can teach us why this is so, tradition and story remind us why it matters.

The teachings of Nanabozho remind us that “the earth endows us with great gifts . . . [but] it is our work, and our gratitude, that distills the sweetness.” Photo by Candie Ward.

To be sure, Kimmerer is a scientist as well as a storyteller; she is matter-of-fact about the warnings of climate change, the consequences of habitat loss, and the simple reality that "just about everything we use is the result of another's life." But the message is made palpable when conveyed through the weaving of a black ash basket: "our lives depend on one another, human needs being only one row in the basket that must hold us all."

The beauty of the author’s prose and the precision of her metaphors are gifts, and according to the Honorable Harvest, they create a measure of debt. How will each of us choose to return the favor?

“In a world of scarcity, interconnection and mutual aid become critical for survival. So say the lichens.” Photo by Larry Albee.

Our Community Read is, in itself, an act of reciprocity. Read Braiding Sweetgrass. Think about the ideas it contains. Engage in one or more of the events offered by Longwood and our partnering institutions. Through the power of story—the most human of gifts—we plant the seeds for the actions we might take to renew our relationship with the land.

"There is hope in the telling of a story, just as there is hope “in the way a seed lands in a tiny crack and puts down a root and begins to build the soil again.” Photo by Shawn Kister.

For the staff and volunteers at Longwood, sharing our Gardens—its stories and its science—is an act of reciprocity with the land, with this place that sustains us. Our founder, Pierre S. du Pont, acted to save the trees of Peirce's Park when, in 1906, he purchased the land that would become Longwood Gardens. Today, we continue to preserve, improve, and carry forth this legacy. We pursue an active plant research program and a "Soil to Sky" approach to land stewardship; we provide educational opportunities for all ages and backgrounds; and, in 2014, we opened our new Meadow Garden, which creates much-needed habitat for a variety of ecological communities.

"In the true spirit of sustainability, the cedars of the old growth forests taught us that “wealth meant having enough to give away." Photo by Ginny Levy.

“All gifts are multiplied in relationship. This is how the world keeps going.” Photo by Adam Cressman.

Our legacy, however, is made complete—pulled taut and strong—by those of you who visit. Next time you're here, slow down and take a good look at the Garden you’re in. Kimmerer says that “paying attention is a form of reciprocity with the living world." Stop and chat with a Gardener digging in the dirt or with a volunteer watering plants. Ask them about what they do; listen to the answer. Tell them a story of your own—how a visit to this place made a difference in your day, how a walk in the Meadow changed your view of the land. Each of you may come away with a lighter step and a strengthened resolve that place matters, that it’s worth our attention, our gratitude, and our care.

Books, like baskets, are carriers of culture, through which tradition and knowledge are handed down—from the Thanksgiving Address of the Onondaga Nation, to the rather amazing botany of lichen. Like a braid of sweetgrass, a book can weave threads of new ideas into your life. Like a black ash basket, our Community Read weaves those ideas into a conversation that holds us all.

Please come listen and join the conversation when gifted author Robin Wall Kimmerer visits Longwood Gardens for a special Community Read Conversation at 2:00 pm on Sunday, April 12.

"That September pairing of purple and gold is lived reciprocity; its wisdom is that the beauty of one is illuminated by the radiance of the other. Science and art, matter and spirit, indigenous knowledge and Western science—can they be goldenrod and asters for each other?" Photo by Cathy Matos.

Opening author quote (blog teaser) from "Reclaiming the Honorable Harvest: Robin Kimmerer at TEDxSitka," YouTube video, 17:57, published August 18, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lz1vgfZ3etE.

Remaining quotes from Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2013).