Water—not only does it sustain us with the fruits of our gardens and fields, it elevates our lives with its elemental beauty. This dual nature of water is embodied in the Gardens and fountains of Longwood, where utility and wonder thrive side by side. Essential to life in the Gardens, water is also a wellspring of play and artistry that finds expression in our fountains, which are monuments both to nature and to human ingenuity.

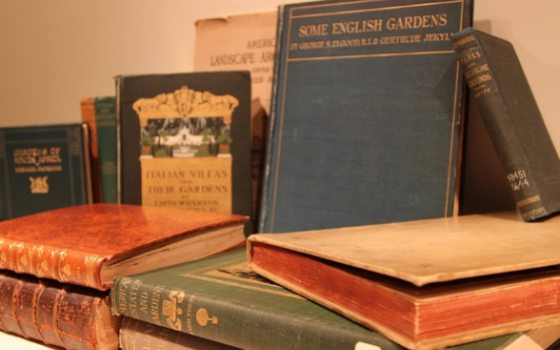

Such human ingenuity was a defining trait of Longwood’s founder, Pierre S. du Pont. And yet even the most imaginative ideas build upon the knowledge of what has come before. Mr. du Pont "collected" ideas for gardens and fountains during his many trips to Europe and to world's fairs, and then implemented them at Longwood, shaping them according to his own American vision and innovation. He also gained inspiration from the pages of his personal library, a tradition that continues today when staff, students, and volunteers step into the Longwood Gardens Library & Archives.

Like water, knowledge both sustains life and elevates it; and our books and libraries are the legacy fountains through which information flows. Beyond the library windows, engineers and artisans raise our knowledge of waterworks to New Heights in the Main Fountain Garden Revitalization Project; inside, on the library table, two rare books in Longwood’s collection give voice to ideas that came before.

But even as the beauty of a fountain springs from both the play of water and the artistry of the stonework, the lure of an old book comes not only from the ideas it contains, but also from the physical nature of paper, print, and binding.

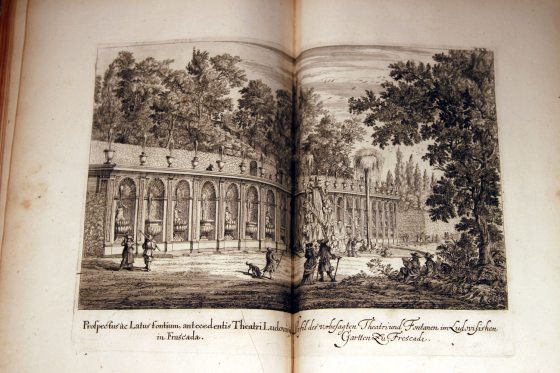

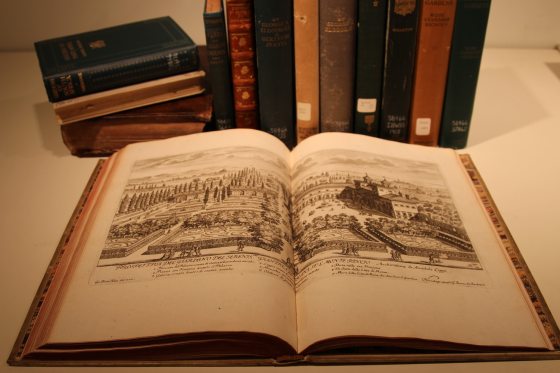

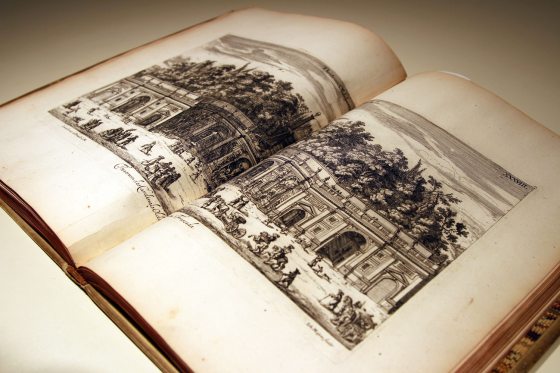

On the table lies a folio, named for the way its paper is folded—each sheet folded once to make two leaves, four pages. This book has traveled long and far, and clues to its provenance are revealed by its English binding, German typesetting, and engraved Italian plates.

Its cover is of vellum, and the red morocco label on its spine contains the book's only English: "Roman Gardens / Falti." Inside, the shiny marbled end papers are characteristic of its nineteenth-century binding. The title page and text are in German—Der Romischen Fontanen—printed in Nurnberg (Nuremberg) in MDCLXXXV (1685). The illustrations retain the Italian inscriptions of their author, Giovanni Battista Falda.

Falda (1643-1678) was an Italian draftsman, known for his architectural vedute (views) of Roman buildings, gardens and fountains, including the renovation projects of Pope Alexander VII. He learned etching and engraving as an apprentice to Giacomo de Rossi, whose family owned the most succcessful Italian printing press of the time. Falda later made prints for upper-class young men on their European “grand tours”—part of their gentlemanly education in art and culture.

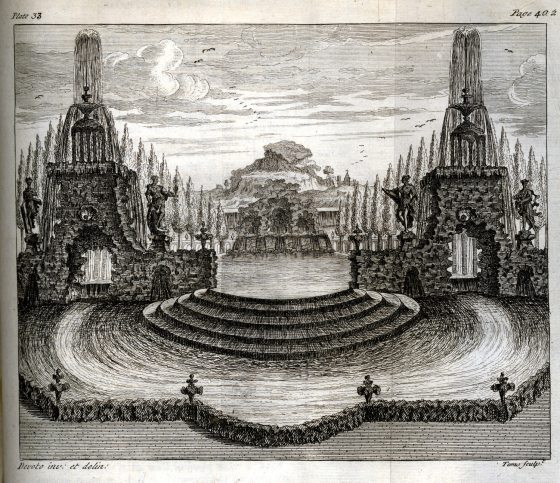

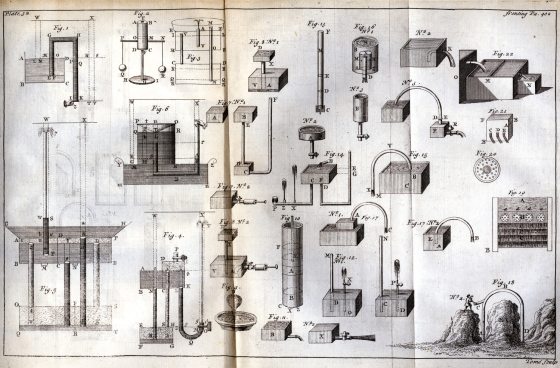

If Falda’s work celebrates the beauty of fountains—and provides a pattern book from which, perhaps, a gentleman-farmer of Europe could plan his estate, as Pierre S. du Pont, himself, was influenced by the great fountains of Europe—then the second book on the library table provides the working manual. An Universal System of Water and Water-Works, Philosophical and Practical (1734), by Stephen Switzer, bears the stains of the water that is its subject, and its appearance is that of a well-used handbook.

Switzer (1683-1745) had a background in English landscape gardening and estate management that included the use of fountains and cascades. He sought to promote a “Farm Like Way of Gardening,” and was influenced by Classical Roman theory. In his own words, Switzer’s work includes “all that can be said on the Rising or Spouting of Water in Fountains.” It also touches on the history of “the stupendous Aqueducts” of Rome, the physics and properties of water, descriptions and drawings of pipes and pumps, and actual plans for gardens and fountains.

And while this book provides details of the physical science of “Hydrostaticks and Hydraulicks” that underlies the creation of fountains, the book itself bears the marks of the physical trades that created it—papermaking, printing, and bookbinding.

In both these rare books, one can look at the tail of a page for the catchword, the first word of the following page used to help order the pages for printing; and the signature of collation, the alphanumeric notation that tells how the printed sheets should be folded and gathered. One can also see the chain and wire pattern of handmade paper, the raw material or “stuff” of which was usually linen rags. Binding in the hand-press period (1500-1800) was a separate craft from printing, and every book that was bound was done by hand.

Der Romischen Fontanen displays these individual processes: the Italian captions are in the native tongue of the original engraver; the text of this German copy is in the language of the printer; and the nineteenth-century English binding provides evidence of an owner far removed, both in time and place, from the book’s origins.

These two books, though they were not a part of Mr. du Pont’s personal library, are similar to the books he collected and by which he probably was inspired while building his gardens and fountains. Together, they not only reflect the wonder and function of fountains, they also mirror the passion and the know-how of the man whose vision brought fountains to Longwood.

Books are collections of ideas. They are, in part, how we know what we know, and how we pass that knowledge to others. But the physical nature of books lends them an essence beyond the words they contain. Through idiom and illustration, through paper, font, and binding, they provide clues to the times and places through which they traveled.

Thus, like water, books possess a dual nature. They are physical and ethereal, functional and beautiful, inscribed by the hand both of man and of nature—like the fountains and Gardens of Longwood.