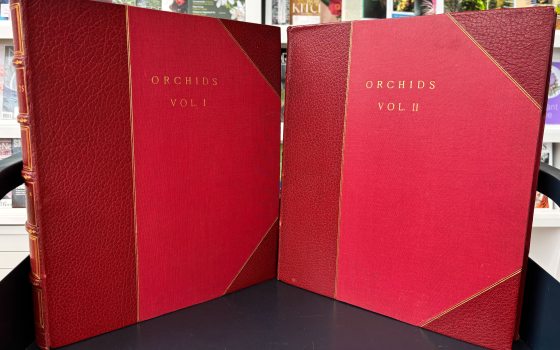

The Longwood Gardens Library was very fortunate to receive a recent gift reflective of our commitment to the conservation of native orchids: a rare 1931 two-volume set of Orchids of the North Eastern United States photographed from nature and published by American fine arts photographer Edwin Hale Lincoln. In these stunning photography books assembled by Lincoln himself, who was known for his unique process and use of platinum prints, he sought to document "every orchid known to grow in the United States east of the Mississippi River and north of the parallel of Washington…. to preserve in permanent form a perfect record of a native botanical family which is the victim of its own loveliness, and is already but a name to many who dwell beside its former haunts." This could not be a more appropriate gift to Longwood, as we share a dedication to the conservation of native orchids—some of which, as photographed by Lincoln, have indeed been lost from our area since.

Lincoln (1848-1938) took up photography in 1877 and started regularly photographing trees and flowers in 1883. He moved to the Berkshire Mountains in 1893, where he began his systematic photographic study (and magnum opus) Wild Flowers of New England. As with the later orchid book, Lincoln’s goal was to document as many plants as he could. He printed each platinum print—the only printing process he used—and attached each image in each volume himself. Lincoln always used an 8-inch by 10-inch box camera with no shutter; he also used a blanket to cover the whole camera, then lifted a corner of it to expose the light. This unique process gave sharp detail to the image, and platinum prints degrade less over time than other types of prints.

Cypripedium reginae, as photographed by Lincoln. In the introduction to Orchids of the North Eastern United States, Lincoln states that “The beauty and strangeness of the orchid lies in its tragedy as a wild flower, and the rarer the species the greater its danger of ultimate extermination.” Image: Massachusetts Horticultural Society.

Cypripedium reginae is a truly spectacular species that can still be found in Pennsylvania, but it is very rare and now confined to a few small populations in the northwest corner of the state. Seeing it in flower is an unforgettable experience. Photo by Peter Zale, Ph.D.

Lincoln’s belief that his photography would help to preserve wild flowers and orchids was likely a result of the growing conservation movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as realization dawned just how much population and industrial growth affected our flora and fauna. He stated in a 1916 Countryside Magazine article that “There is no record so true as the good photographic study; and as we see the conditions of plant life eternally changing everywhere, the value of these permanent authentic records to future generations cannot be over-estimated."

These donated volumes are certainly a beautiful and important photographic study, and we will care for them and share them with future researchers. The volumes were a gift of Patricia L. Gower, given in memory of her grandfather, orchid grower Oliver Lines, who was a founding trustee of the American Orchid Society. Longwood Gardens founders Pierre and Alice du Pont were charter members of the American Orchid Society and had a great passion for orchids. Despite Lincoln’s warning that orchids were rare and requiring protections, many of the orchids he photographed have only declined in numbers since he documented them. In fact, some of these have disappeared completely from the Northeast, and especially Pennsylvania, where at least six, and likely more, of the approximate 60 orchids historically known from the commonwealth are now considered extirpated (extinct from the state). Many others are considered endangered and the precious few populations that remain are still threatened by habitat loss and now further impacted by invasive species and a changing climate.

At the time when Lincoln was photographing orchids, the technology used to propagate orchids from seeds was in its infancy and the only option for conserving native orchids was to protect the places where they grew. As that was the only option, native orchids developed an almost mythical reputation for being impossible to cultivate in gardens and impossible to propagate from seeds. Within the last 30 years, however, significant advances in laboratory techniques have been made in propagating orchids from their tiny dust-like seeds, paving the way for advances in conservation of native orchid species through seed collection and propagation.

In 2015, Longwood Gardens embarked on a native orchid conservation program through adapting known propagation methods for native orchids and using original research to develop techniques for propagating understudied species. Through this work we have been able to further define the role that horticulture can play in plant conservation, and have generated large numbers of plants for restoration of native populations and to trial as garden plants. Use of native orchids as garden plants has the potential not only to educate guests about the orchids that can be found in Pennsylvania and allow guests to enjoy their beauty, but can also relieve pressure on wild populations since these plants can be seen in our Gardens, rather than in their fragile native habitats.

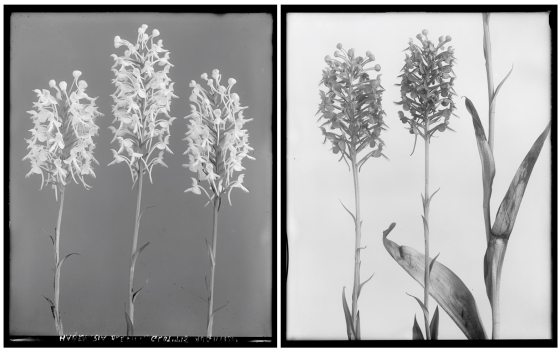

Cypripedium candidum (left) and Habenaria leucophaea, now known as Platanthera leucophaea (right), as photographed by Lincoln. Both have since become extinct in Pennsylvania. Images: Massachusetts Horticultural Society.

One of our conservation goals is to return Pennsylvania extirpated orchids to the state. The small white lady’s slipper can still be found in one secret location in Maryland. We worked with partners there to collect seeds and propagate this rare and beautiful species. Photo by Peter Zale, Ph.D.

Many of the orchids mentioned by Lincoln have been incorporated into our native orchid conservation program, and some can now be seen in the Gardens. Of particular interest is Lincoln’s plate showcasing the white and orange fringed orchids (Platanthera blephariglottis and P. ciliaris) and their putative hybrid, known as P. × bicolor.

P. blephariglottis (left) and P. ciliaris (right), as photographed by Lincoln. These orchids were identified with the genus name Habenaria, which was used when Lincoln published his work in 1931. Images: Massachusetts Horticultural Society.

These are among the showiest orchids in Pennsylvania, but also among the rarest with only two small populations known in the northeastern corner of the state. Fortunately, they are easy to propagate and we have planted the first display plants in a new bog garden in the Idea Garden, where the first flowers should appear this summer.

This select individual of Platanthera × bicolor was grown from seed at Longwood and provides a perfect example of why it was named “bicolor”. The seeds used to propagate this individual were from the last remaining population of this species in Pennsylvania. Photo by Peter Zale, Ph.D.

Even with advances in the technology of propagating orchids, many remain difficult or even impossible to propagate and continue to decline in the wild for unknown reasons. This challenge underscores the importance of historical accounts of the species, such as Lincoln’s, over time since they can serve as a record of occurrence in areas where orchids may have once grown but are now gone. They also provide hope that species such as the Eastern Prairie fringed orchid (Platanthera leucophaea) and Cypripedium candidum, now extinct from Pennsylvania, may still be found again one day. Public gardens like Longwood have the opportunity to advance orchid conservation through these methods, but a lot of research and development remains to be done.

Editor’s note: Our core collections, including our orchids and our work to conserve them, are supported through gifts, both large and small, each year. Learn more about how you can support our efforts to save endangered plants.