This article first appeared in issue 294 of Longwood Chimes, from Winter 2017.

The Main Fountain Garden debuted in its illuminated form in September 1931. But refinements continued well into the 1930s. Hydraulic experiments resulted in some pump reassignments and the addition of the eye-catching Tree Jet and Fishtail effects to the Rectangular Basin in 1933. Massive planting continued through 1935. The carved stonework was also completed by that year, including replacing water steps in the center of the Upper Canal with walkable stairs built over a gushing shell.

The two smallest canals were embellished with blue tile. A stone Love Temple was erected on the Game Lawn (next to today’s Idea Garden) to provide a focal point to accentuate but balance the asymmetrical extension of the garden to the west. The Waterfall was given an upper level, and an above-ground stream was dug and lined with rocks to connect the hilltop reservoir with the falls. By 1938, the Main Fountain Garden was finally finished.

During Pierre du Pont’s lifetime, the Main Fountains were illuminated at full capacity after private evening parties, after dinners for service and professional organizations, and for University of Delaware summer student gatherings. The public enjoyed them mainly after Open Air Theatre charitable events for which tickets were sold. The Theatre fountains would follow the stage event, then the audience would walk over to the Main Fountain Garden for a half-hour show. In 1932, the first full year of operation, there were 24 evening displays. This schedule continued with some variation until World War II when Longwood greatly scaled back. There were no shows from 1942 to 1945, and the nozzles were removed and hidden lest they be confiscated for metal. As Pierre noted in 1942, “We are having very few visitors these days, practically none. The place seems deserted and less like a public park.” After the war, the schedule resumed and Open Air Theatre performances again ended with a short stage fountain display after which guests usually enjoyed a Main Fountain Garden show.

Pierre du Pont passed away in April 1954. That summer, the Longwood Foundation sponsored the first free evening show for the general public on Tuesday, August 24, 1954. About 2,500 people attended. Phil Brewer reported that “the public were definitely appreciative as shown by their exclamations and applause during the fountain display. Many were overheard making favorable comments and expressions of hope for future displays and all who were talked to freely proclaimed their enjoyment of the display and said they would tell others if more displays were given in the future.” The cost of the display was about $40 for labor and electricity.

The next year, 1955, evening displays were given once every three weeks from May through October. Over the decades these gradually grew into as many as four evening displays a week, which adds up to about 475 shows during Pierre’s lifetime and 2,750 shows since, totaling 3,225 illuminated displays through 2014.

In 1984, as a marketing initiative, the term “Festival of Fountains” was coined as part of a year-round festival concept initiated to celebrate Longwood’s different seasons. Soon there was a performing arts event before every evening fountain display.

During Mr. du Pont’s time, the Main Fountains were operated at a reduced “static” display from 2 to 6 pm daily during the fountain season, but eventually they ran all day. In 1962, special 15-minute shows at full capacity were offered at 2 pm on weekends and holidays, and 15-minute shows at 4 pm were added in 1963. These twice-a-day weekend shows (manually operated by an electrician) were publicized every year through 1974. Daily automated 5-minute full-capacity shows began in 1987 at noon, 2, and 4 pm. Viewing the daytime fountains at full throttle became a highlight for casual visitors. In 1999 and 2002, however, state-imposed drought restrictions eliminated daytime but not evening displays.

In 1934 Pierre du Pont invited some friends to privately view the illuminated fountains, noting, “If you will give me a couple days’ notice, I shall be sure to have a good demonstrator on hand.” The foremost among those was the man responsible for designing the electrical control systems, Phil Brewer, who wrote in 1937: “By mixing these five colors [red, blue, green, yellow, white], innumerable shades, tints and blends may be obtained and usually the operator improvises continually. He may follow a sort of routine or sequence of color combinations but he is continually finding new and prettier combinations and then tries to remember them for the next time.” Longwood’s electricians used to relate how Mrs. du Pont would observe a color combination that she particularly liked, telling the operator much to his chagrin, “How’d you do that? Do that again!” Recreating the effect was almost impossible. Although this took place at the Open Air Theatre, it would be equally applicable to the Main Fountains.

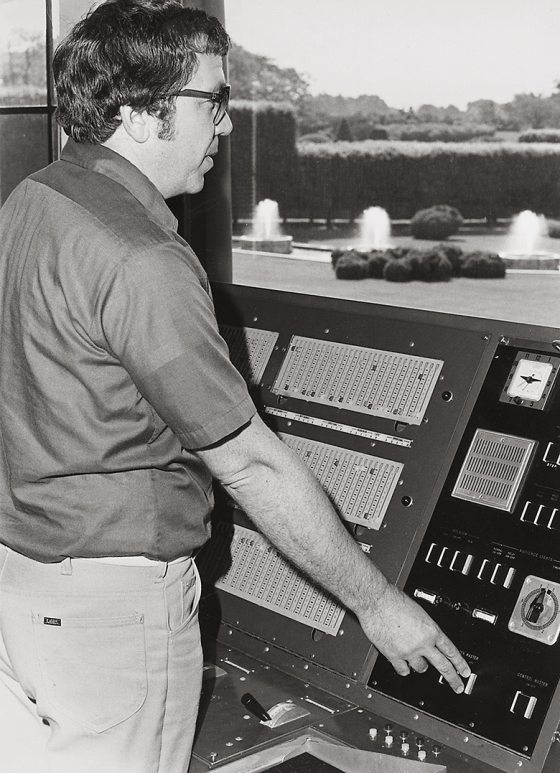

Phil Brewer retired in 1960, but he was retained for a year as a special consultant to plan the electrical rebuilding of the fountains. It was a complex job, and he told one visitor that “it is such a big project that happily I will be retired before they do it.” By 1963, it was recommended that the old motorized rheostats be replaced with the latest electronic dimmers. Furthermore, “the proposed system offers the advantage of a programmed display which could be arranged to eliminate ‘clashes’ of color during the cross-fading operation by color coordinating displays.” The original equipment was removed after the 1965 fountain season and was replaced with a new theatre lighting system costing $60,000 that was first used to control a public display on May 15, 1966.

Control systems weren’t the only changes faced by the Main Fountain Garden. Mother Nature could be brutal, and never more so than in 1958 when a massive snowstorm broke apart many of the magnificent boxwoods. Thus began years of replanting boxwood or, as a substitute, Japanese holly.

In addition to daily maintenance, the Main Fountain Garden required periodic renewal over the years. Some of these efforts were practical, like new Canal copings in 1957 and 1958, replacement blue tile in 1960, new pump parts in 1963, and valve rebuilds in 1966. The first significant addition was conceived in 1962 as a rain shelter around the “quite unsightly” hilltop reservoir that fed the Waterfall. Director Russell Seibert recalled an unusual water feature he had seen in Costa Rica: the Fuente de Ojo de Agua, built in 1938, was a circular “eye” feeding a swimming pool with 3,170 gallons per minute of spring water. Using it as a model, Longwood commissioned civil engineer Iraj Zandi from the University of Pennsylvania and graduate student George Govatos to conduct hydraulic tests, and their findings resulted in the Eye of Water, placed into operation in 1968. The surrounding pavilion was designed by Victorine and Samuel Homsey, Inc.

An even bigger change came about shortly thereafter. Pierre du Pont had designed the southwest corner of the fountain garden with an arched iron trellis to extend the pumphouse wall. The nine bays were covered with vines arching over curved “sleigh” fountain basins. Although it was later said that Mr. du Pont had never really finished this corner of the garden, early drawings prove that the trellis was included from the start. By the 1960s, however, it was deemed too difficult to grow plants effectively on the structure. The freestanding trellis was removed in 1965.

The arched trellis in its heyday, September 22, 1956. Photo by Eugene L. DiOrio. Gift of Eugene L. DiOrio. Longwood Gardens Library & Archives.

Arched iron trellis in March 1965, prior to removal. Photo by Gottlieb Hampfler. Longwood Gardens Library & Archives.

The Wilmington, DE architectural firm of Wason, Tingle, and Brust (successor to E. William Martin’s firm so favored by Pierre du Pont) designed the building extension and plaza, which was finished by 1970. The project included two new bridges over the Lower Canal to permit more direct access through the garden.

This was followed by a major replumbing of the Main Fountains from September 1970 until June 1972. Almost 11,000 people visited on the day of the well publicized final display before the 22-month fountain shutdown. Included were new wiring, motor starters, some replacement fountain light lenses, and additional Indiana and Italian limestone. The upgrades continued until 1977 with the unanticipated replacement of the 36-foot-long header, a giant pipe in the Pumphouse that supplied all the booster pumps with water. The four main valves controlling water from the hilltop Eye reservoir were also replaced.

In March 1971, famed California landscape architect Thomas Church was engaged to advise on long-range planning, garden improvement, and visitor circulation. He proposed re-working the Conservatory observation esplanade and adding a new terrace connecting the Lower Canal to the three-arched loggia centered on the south fountain wall. Architect Richard Phillips Fox from Newark, DE prepared the detailed plans. The terraces were completed in mid 1973 and were the last major hardscape changes. But the garden continued to evolve in other ways.

Pierre du Pont was a passionate music lover, and he embraced the latest technology to make music accessible on a daily basis through pianos, organs, and a carillon that all could be played automatically via paper rolls. So it is not surprising that he agreed to fund an invention to synchronize music with colored light, the creation of Mary Hallock Greenewalt, sister of Pierre’s sister-in-law Mrs. William K. du Pont. The resulting “color organ,” used for a luminous piano recital at Longwood in 1926, was acclaimed yet beset with problems; the full story was told in Issue 291 (Summer 2015) of the Longwood Chimes.

In 1930, the General Electric Company tried to interest Mr. du Pont in their electronic dimming system for the Main Fountains, noting “the future possibility of synchronizing lights with music, on which our radio engineers are already working, and the immediate possibility of setting up a scene during one color symphony and the initiation of the second complete symphony at the flick of a switch.” But he thought it too complicated for “casual” use.

It is likely that Pierre visited the 1933–34 Chicago World’s Fair and the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair, both of which featured illuminated musical fountains. In 1941, he responded to a suggestion that music be incorporated with Longwood’s displays, noting “We have had a number of similar suggestions…. After a number of trials the attempt was given up, as the relation between the color combination and the music could not be made effective…. we made several experiments on making the water move in rhythm. It was interesting for a short time, but we found our apparatus inadequate for a long performance, which, moreover, seemed to get tedious after continued applications.” Following his death, the idea was discussed again in 1960, 1973, and 1977.

Finally, in 1980 music was added to the fountains. The concept was developed by staff member Colvin Randall, who first enjoyed musical fountains as a child at Wanamaker’s in the late 1950s and as a teenager at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Randall had played complex pipe organs for 15 years, so coordinating fountains to music was relatively easy. From 1980 to 1983, musical shows were performed using cue sheets keyed to the 1966 lighting console.

Around 1980, Richard Gray from R.A. Gray Inc., of San Diego visited Longwood by chance, saw the fountains, and proposed automating them using his show control equipment. His computers were installed by 1984, permitting infinite jet and color control within the limits of the existing plumbing and wiring. The programs were scripted using two basic commands: SWITCH for the jets, and FADE for the lights. Hundreds of hand-typed commands were assembled by the computer into a complete show, synchronized to music using a SMPTE time code. It may seem complicated, but it worked like a charm. The original computer was replaced in 2002 by its successor, “System i,” a much faster Windows-based product developed by Robert Harvey from The White Rabbit Company but with the same command structure.

The soundtracks chosen to accompany the shows evolved over the years from French baroque “garden music” written for Versailles to Russian romantic masterpieces (Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff), patriotic Sousa scores, Gershwin, Big Band, movie music, and pop. Very few, if any, presenters elsewhere have dared to produce half hour fountain shows devoted solely to one composer, such as to Khachaturian, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, or Wagner. Single-themed shows have also included ABBA, the Beatles, Leonard Bernstein, and Elton John.

The icing on Longwood’s fountain cake has no doubt been fireworks.

The icing on Longwood’s fountain cake has no doubt been fireworks. Pierre du Pont was fascinated with pyrotechnics but presented only six large displays at the Gardens up through 1930 and never with fountains. He probably thought his “liquid fireworks” were sufficiently spectacular by themselves.

A half century later, in 1979, Longwood staff members attended a Fête de Nuit at Versailles and were impressed with the potential for combining fireworks with fountains. Discussions began that winter with the Vineland Fireworks Company from New Jersey. A few test effects were tried one evening after closing. On June 14, 1980 (Flag Day), the first fireworks and fountain show ever at Longwood was presented (without music) in the Main Fountain Garden. A second show (with recorded carillon music) was staged on August 16. Three shows set to orchestral music were held in 1981, and since then three to six shows (and 10 in 2006) have been scheduled each year.

From 1980 to 1983, the fireworks were supplied by Vineland, initially synchronized from the fountain control room using walkie-talkie cues, then by voice cues on one track of a stereo tape. The French company Ruggieri designed and fired the shows from 1984 to 1992, using many of the same lowlevel effects and Roman candle techniques they employed at Versailles. Two highlights were always a stunning illumination of the hillside and trees behind the fountains using intensely bright mega-bengales flares, and a French-style bouquet finale building from the ground up to a breathtaking conclusion. Beginning in 1984, cues were signaled with a light in the firing room triggered by the fountain computer. Subsequently a timecode was sent directly to the fireworks control box.

From 1993 to 2006, Longwood’s displays were produced by Pyrotechnology, from Boston. The company, founded in 1980 by Ken Clark, was known especially for its Fourth of July fireworks productions on Boston’s Charles River Esplanade in conjunction with the annual Boston Pops holiday concert. From 2002 to 2006, International Fireworks of Douglassville, PA presented additional displays in the Gardens. From 2006 to 2011, Celebration Fireworks of Emmaus, PA produced special shows for TV broadcasts and New Year’s Eve festivities at Longwood. Rozzi’s Famous Fireworks of Loveland, OH fired the major summer displays from 2007 to 2009, then Arthur Rozzi Pyrotechnics from Ohio took over in 2010; coincidentally, they custom manufactured many of the shells used by Pyrotechnology in previous years.

In total, more than 150 fireworks shows were presented at Longwood from 1980 through 2014.

Yet despite all the spectacle and acclaim, the Main Fountain Garden had seen better days. Repairs were required more frequently. The southwest fountain wall pool was redone in 1987 with new tile, but soon thereafter the entire façade and terrace above were cordoned off for safety. Underground pipes would break, particularly in an area humorously named The Zipper southwest of the Lower Canal that had to be dug up repeatedly. Other breaks flooded the main supply pump motors. The limestone was falling apart. The handwriting was on the wall—it was time to completely rebuild.