A day in the life of a virtual educator is one of many questions, new faces, faraway places, and exciting connections. From exuberant students dressed in white lab coats in Mexico, to hearing-impaired students signing through an ASL interpreter in Kentucky, to indigenous Inuit students in plant-sparse remote Canada, plants are our common language … and our innovative Virtual Field Trip program is the medium through which we happily connect.

For more than five years, Longwood Gardens has offered fun, interactive, free virtual programming to public and private schools around the world via our Virtual Field Trip program, improving science knowledge and introducing 10,000 students per year to the exciting possibilities of a career in horticulture. No matter their location, students can connect with Longwood and even go to areas of the Gardens that even onsite students don’t see, such as our Research and Production Facility, during these live lessons, delivered directly to the classroom.

These connections are made possible by Longwood’s interactive video conferencing studio, which looks very much like a TV studio with green screen technology, lights, and camera. However, the technology to connect Longwood with participating students is relatively simple. Schools require only an Internet connection, microphone, speakers, webcam, and projection source to connect.

Perhaps one of the very best moments experienced during a Virtual Field Trip is when students first realize I can see them and talk to them, just as they can see me and talk with me. No matter the age group I’m teaching, or their location, a Virtual Field Trip always begins with that same “aha” moment.

One half of the classroom begins to wave as they see themselves on screen. The second half notices the screen image has changed, signaling program start. When I wave back at them, I’m met with “Wait, she can see me? I can talk to her?” And so begins another question-filled experience.

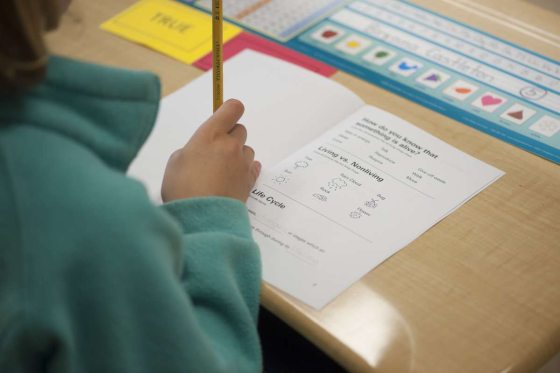

Schools participating in our Virtual Field Trips can select from eight different curriculum-based programs for grades K–12, ranging from Carnivorous Plants for grades 3–8, to Plant Survival for grades 7–12. We also offer a free demonstration to schools new to the program. A Plant’s Life, the most popular lesson for first through fourth graders, chronicles the journey of an angiosperm through its life cycle. The virtual visitors follow the instructor in their Longwood workbooks, diagraming and drawing each stage of growth, proudly displaying their works of art after adding the sun and rain for seed germination. The “oohs” and “aahs” typically increase as we reach the flower stage in the plant’s life cycle, as the students are enthralled by a digital story filled with Longwood flowers from all seasons, inside and out.

Each and every Virtual Field Trip has its blockbuster moments, such as second graders in Mexico City proudly displaying their starched, crisp, pure white lab coats, eagerly awaiting the introduction of an experiment. Just like our Longwood horticulturists in the Research department, they too will conduct an experiment—theirs to ascertain whether a lima bean seed will grow in something other than soil.

More than 70% of schools participating in our Virtual Field Trips are repeat virtual visitors, such as third graders in a neighboring Pennsylvania school district who partake annually in two Longwood lessons, Tropical Plant Adaptations and Desert Plant Adaptations, that have been written into their curriculum. As part of their collaboration with Longwood, they nervously present their classroom projects virtually, comparing and contrasting diverse biomes … but also prepared to ask a myriad of questions about careers in horticulture. They often ask me as many questions as I ask them.

Each Virtual Field Trip ends with student Q&A time, with such often-asked questions as:

How many flowers do you have at Longwood? What’s the tallest plant? Why does a seed need sunlight if it’s covered with soil? How does a Venus Fly Trap eat? How many people work at Longwood?) What do you like best about your job?

My answer to that last question? Meeting 10,000 new faces in new places and all of the questions.

With Virtual Field Trips, new vocabulary, new ideas, new technology, and new teaching tools creates a learning experience for all. Students learn about new topics and concepts relating to plant science, as well as get a look into the world, and careers of, horticulture. And that’s a seed we’re happy to plant.