As part of the Fellows Program, our 2019–20 Fellows spent time at individual field placement sites around the globe. They had originally intended on spending a full two months at their respective field placement sites—a plan that had to be altered with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. While their travels were cut short, their experiences will last a lifetime. Here, they reflect on their time spent at their host organizations, and their lessons learned along the way.

Shawna Jones, Singapore National Parks Board, Singapore

Singapore is a city, state, country, and an island. It is in constant transition—growing, thriving, and ever-expanding. If it needs more space, it expands its shores. If there needs to be more dwellings for the growing population, their buildings go higher. And if becoming a “city within a garden” was not cool enough, they are now in transition to the idea of letting nature take back its land, and Singapore is becoming a “city in nature.”

My project while I was in Singapore was to establish a resource list for potential youth engagement programs that Singapore’s NParks could establish through their extensive parks systems. Parks in Singapore have been utilized as thoroughfares more than for designated activities, and Singapore would like to see more youth spending time in their spaces. I was able to write a compendium of resources based on American youth engagement programs in botanical gardens, as well as write a lesson plan for therapeutic gardens in Singapore.

Singapore is, by far, the greenest urban playground I have ever visited. You look up at the tall buildings while walking around downtown not to see concrete structures and plain windows, but gardens spilling from the walls and off of the roofs. The smells of orchids and wild ginger fill the air, along with the smells of one of my favorite Singaporean staples, the Hawker center. Singapore has been able to capitalize on its location and unique history of being one of the most inclusive cities in the world, where the ethnic make-up of Singapore can be Indian, Malaysian, Chinese, and just people of the world. There is no one look for a Singaporean, and with that comes a beautiful melting pot of foods, languages, and cultures.

But I am not writing to gush about how wonderful it is to explore this unique city and all of its rare offerings. I writing to let everyone know about NParks, the National Parks Department of Singapore. Singapore has a unique mindset that pushes it to strive to be the best, the most forward-thinking, and not to limit itself or its possibilities. It is not a cliché to say, in Singapore, the word “can’t” does not exist. Nor is it to think, “If you can dream it, you can do it.” Why can’t you have a population that grows while simultaneously generates less waste? Why can’t you have a booming economy but replace up to 90 percent of all of the vegetation destroyed in the development of new buildings and condos? In Singapore, these aren’t just ideas; they are realities. All of this is accomplished because of Singapore’s unique mindset about how their densely urban environment needs to grow in tandem with their preservation of nature.

Singapore’s NParks does not live within the Ministry of Environment but rather resides with the Urban Development Authority. When Singapore gained its independence 60 years ago, Singapore started to see a massive increase in its economy and, subsequently, their residents and people immigrating to the island. Singapore does not have any natural resources, therefore, the preservation of what makes Singapore beautiful became of utmost importance. Singapore’s rule of replacement states that with every new building, the city-state is legally required to ensure that 40 percent of the destroyed environment is restored to its preexisting condition. Singaporeans took this to the next level, and now building developers routinely surpass this requirement and more consistently hit 90 and to 100 percent replacement status. The results are impressive. Buildings are masked behind living walls, you walk throughout corridors of breathing landscapes, and there is a plethora of skyscrapers that boast active jungles as their roofs.

It is truly a unique experience to explore this “city within a garden” as it immerses you within nature right in the middle of a mega-metropolis.

Abra Lee, Château de Villandry, France

I was in the sixth week of my field placement assignment at Château Villandry in France when I received word in the middle of the night that I needed to travel back to the US. I sat on the edge of my bed in shock, panicked even. I had to pack—immediately. There was a ticket back to the US in my inbox. No goodbyes for the friends I had made in France. No closure. I was gone by sunrise. Even in my hurried exit, what was never lost on me during my experience was the art. Château Villandry is a whole vibe, it is art.

The very definition of cultural art is to help us develop the mind and body, refine feelings, thoughts, tastes, and reflect and represent our customs and values as a society. Cultural art is music, art, drama, dance, and, of course, gardens. The owner and great-grandson of the founders of Château Villandry, Henri Carvallo, leads the garden with the controlled artistic flare of a conductor of a great jazz orchestra. His team are the master musicians. They depend on each other to create a rhythm and flow while making beautiful imagery through plants. Being exceptional is their norm. They don’t cut corners; they don’t skip steps. They are devoted to beauty and are confident in the art they create, as they should be. They are artists.

During my time at Château Villandry, I worked on two main projects. The first was an exhibition titled “Ann & Anne: Renaissance Gardens” which explores the parallels of the garden matriarch Ann Coleman Carvallo at Château Villandry and another matriarch, Anne Spencer, of the Anne Spencer Museum and Garden in Lynchburg, Virginia. Focusing on incredibly accomplished women whose stories aren’t often told, the exhibit tells the story of Carvallo, who headed a French Renaissance garden, and Spencer, who was part of the Harlem Renaissance and designed her own garden. The exhibit also focuses on promoting friendship and the exchange of knowledge between France and the United States, as part of a mission set forth by Coleman’s son, Francois Carvallo.

My second project was conducting historic research to help inform garden visitors on little-known facts about the garden, going beyond the well-told story of the history of Villandry. We focused on such lesser-known facts as Château Villandry serving as the inspiration for the short story The Mysterious Lodger by British author E. Philipp Oppenheim, considered to be one of the fathers of the mystery drama, as well as the fact that Château Villandry served as the location of the world’s first stamp to feature a monument and a garden.

I don’t speak, read, or write French. The solitude that came with limited communication during my time at Château Villandry deepened my understanding of my purpose and of myself. Want to create, understand, or recognize great art? Then know who you are. The past and coming weeks have changed the world we live in forever. Despite COVID-19 and the dark cloud it has created, we will get through this. The art of gardening will survive, thrive, and rise to again push the culture and the world forward.

Becky Paxton, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, California

There is healing in the trees for tired minds and for our overburdened spirits, there is strength in the hills, if only we will lift up our eyes.

President Calvin Coolidge spoke these words in 1924, just five years after The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Garden was entrusted as a public institution in the shadow of California’s San Gabriel Mountains. Today, the Huntington welcomes more than 800,000 annual visitors and is celebrated as one of America’s most acclaimed botanic gardens. I was honored to spend a six-week field placement among the institution’s botanical garden staff.

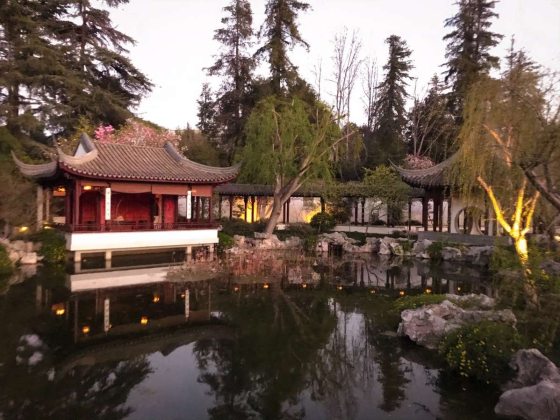

I chose a field placement within my native United States, yet the plants, landscapes, and Mediterranean climate of San Marino, California couldn’t have been more different from my home state of Tennessee. More than 2,000 species of succulents and desert plants, 200 species of palms, and a significant collection of cycads distinguish the Huntington and create a dramatic sense of place. The Huntington’s beautiful 12-acre Chinese Garden, Liu Fang Yuan, is counted among the largest classical-style Chinese gardens in the world. My journey at the Huntington began in this extraordinary garden space, which was in the final stages of a long-awaited major expansion project when I arrived in February.

Attending project meetings and walking the Chinese Garden site, I witnessed firsthand as its construction projects progressed and debut landscaping plans took shape. Interconnectedness between architectural and horticultural features created a sense of total immersion, while scholarship and respect for Chinese design principles guided the planning process. In February, as a programmatic complement to the Chinese Garden initiative, a dynamic symposium on “‘Unscholarly’ Gardens: Rethinking the Gardens of China” brought international thought leaders in the field of East Asian gardens to the Huntington. Its lectures showcased the many motivations and manifestations of Chinese gardens, while attendees ranging from public garden professionals and scholars to community enthusiasts made meaningful connections with one another.

As the sixth week of my field placement came to a close, COVID-19 began to loom as an emerging threat in Southern California and much of the world. I made plans to depart two weeks early to begin social distancing, and took a final walk through the Huntington one Friday afternoon. The sun fell below the hills, and I took this last photograph, remembering the words of Coolidge: There is strength in the hills, if only we will lift up our eyes.

It was when I returned home that I learned that Henry E. Huntington, visionary founder of the Huntington, had declared its purpose: For the uplift of humanity.

Mae Lin Plummer, Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, UK

My experience at Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) was everything I hoped it would be. I was at a plant-saving, rock-your-plant-nerd-world, community-loving institution dedicated to overcoming plant blindness and boldly taking action to address the biodiversity crisis and climate change. There was no better place for me. The gardens are steeped in the significance of place and history and stunningly beautiful beyond words. I was awestruck and humbled as a horticulturist, but also as a leader and how one would lead an organization with hundreds of years of history and legacy.

RBGE has been studying and communicating the relationship between plants and people for 350 years. Sit with that for a spell. Their living collection is made up of more than 13,500 species from 157 countries housed across four gardens in Scotland: RBGE headquarters in Edinburgh (aka “The Botanics”), Logan Botanic Garden, Benmore Botanic Garden, and Dawyck Botanic Garden (pronounced “doyk”). RBGE’s Herbarium holds approximately 3 million preserved plant specimens, almost two-thirds of all the world’s known plants from every country on Earth. I saw a plant pressed by Charles Darwin himself. I have rare moments of humility, but this was one of them.

Visiting and experiencing all the gardens of RBGE allowed me to truly grasp the diversity and significance of their plant collections, each situated in uniquely different landscapes and microclimates.

Logan Botanic Garden is other worldly and an utter horticultural mind trip. It is where plants from Australia, New Zealand, South America, South Africa, China, Vietnam, and many other countries grow and thrive together, with giant tree ferns and palms next to rhododendrons and magnolias, along with so many camellias. It reminded me that the extraordinary and seemingly impossible is possible. Sometimes we must forget the rules, plant something, and just see what happens.

Benmore Botanic Garden is dramatic, from the moment you enter and peer up into a towering avenue of majestic 150-year-old giant sequoia trees, ascend through a collection of more than 300 different species of rhododendron, and continue to climb another 450 feet to a viewpoint of Chilean Araucaria overlooking the 120 acres of gardens below, all surrounded by the West Highlands. Every bend in the path and encounter with towering plant specimens reminded me that I was walking into a vision and dream of a garden by people who knew they would never walk among it themselves. It’s a poignant reminder that we must dream of the world we want to live in and begin creating it even if we will never see it happen. This is the gift gardens and horticulturists share with the world and it is what makes our work more relevant than ever before.

Dawyck Botanic Garden is one of the finest landscaped woodland gardens I have ever experienced. Dawyck’s collection is not limited to what was planted in the past, as they continue to plant 100 to 200 woody plants each year, planning for the next 200 years of visitors and for the unknown effects of climate change. There is an urgency to RBGE’s planning and actions that I wish was more prevalent in the world.

How strange it is to relate to the unknown so personally right now. It is a reminder that the world and our lives have always been uncertain and full of unpredictable twists and turns. But I am comforted and hopeful in knowing that The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh has endured and persisted for 350 years through challenges and triumphs and will continue onwards.

Barbara Wheeler, The Morton Arboretum, Illinois

Seldom do you get the opportunity to view leadership and management in such an intimate way, by being placed in an organization to look through the lens of how others do it. This immersive experience that is the Fellows field placement allows for both observing and asking questions. Who, what, how, and why? Understanding what leadership and management practices you want to take forward, as well as reflecting on your own leadership style, and what behaviors you want to keep the same, massage, or stop doing, are all key to understanding your own journey.

My time at The Morton Arboretum in Chicago allowed me the honor of working in an organization I’d heard about and read about my whole career. It’s an organization that leads the way in scientific research and conservation of tree species, all at an incredible location where 1,700 acres of gently rolling to flat Illinois land is given to displaying tree species and educating actively through programs and in allowing visitors access to its collections.

Field placement gives so much but it also allows you to give back. The privilege of having such intimate access to how an organization runs and is led is balanced with undertaking a project that will provide real value. For the host, having a Fellow’s fresh set of eyes on a system, process, or part of the organization that they wish to review is of immense value. The host gets to see things through the clarity this new person’s lens, one that has not been clouded by knowing the players in the orchestra of an organization. My project was to undertake a review of the executive organizational structure of the Arboretum, which afforded me the opportunity to learn the pros and cons of varying structures through benchmarking of other comparable organizations and through discussions with the wider Arboretum leadership team. The exposure alone to an array of top leaders in the public horticulture field is something I will treasure and take with me to my future leadership roles.

The Morton Arboretum is an organization that promotes employee values of stewardship, collaboration, learning, and excellence—all of which align perfectly with my own values—so it came to pass that The Morton Arboretum was a perfect fit for me. I saw how various leaders come in different packages, not all cut from the same cloth. I saw how humor plays a key and valuable role in leadership. I worked with extremely passionate staff who are all leaders in their respective fields. Regardless of rank, I was welcomed enthusiastically, and time spent talking to me was never considered an imposition.

I am indebted to both The Morton Arboretum’s President and Chief Executive Officer Gerry Donnelly and Vice President of Finance and Chief Financial Officer James Fawley for their transparency in allowing me to experience executive leadership meetings and board meetings, their trust in giving me a substantive project and allowing me to run with it in my own way, and their humor, which allowed me to feel comfortable in a new environment.

I am immensely grateful to Longwood Gardens. Experiences gained from field placement have not only assisted in my leadership journey but also informed me to the value of exchanges with other organizations. Reflecting on my experience, I picture a rich tapestry of learning that is unparalleled and will significantly contribute to my own organization. This value is one of the many lessons I will take back to New Zealand to apply to the public horticulture realm.

Nanette Wraith, The Morton Arboretum, Illinois

Every day during field placement I found myself gripped with an unshakable urge to get outside and explore the wonderful grounds of The Morton Arboretum. When I first arrived, this feeling would manifest itself in the realization that I had taken off my work shoes and was busy tying up the laces of my walking boots, as if my subconscious knew before I did that I was due my daily dose of fresh air, blue skies, and nature. I have always loved hiking. It recalibrates me, allows my brain to disengage from daily life. I can be quiet and observant without any expectations. In short, it is vital for maintaining my own mental health.

Throughout the Fellows Program I have made time to walk or run, shoehorning it in at the start and end of the day. But during placement the only time to explore was during the working day and I started actively scheduling in a daily wander, to discover a little more of the 16 miles of hiking trails each time. When I’d get back to the office I’d notice I was energized and alert, my productivity would increase, and my mood was always calm and positive. I realized these walks were serving a dual purpose of acquainting me with the Arboretum, its grounds, and plant collections, as well as recharging me.

The Morton Arboretum has an extensive special events program. It provides diverse event offerings 12 months of the year, which is no easy feat during the Midwest winter. The goals of special events are two-fold: to attract new visitors to the Arboretum (and show them all the reasons they should return) and to generate revenue to support the organization. My field placement project revolved around creating a set of evaluation metrics to measure financial and audience success for all the Arboretum’s special events. Morton has science and research at its core and so it was essential to enable special events to be evaluated based on data. I used the metrics to fashion a dashboard tool that provides a thorough snapshot of event performance throughout the year, which in turn enables staff to make strategic decisions going forward.

Through my focus at Morton, and my dedication to getting outside while I was there, field placement shifted how I view my time in nature, the strength and purpose of my connection with nature, and the emphasis I put on it. Instead of squeezing it in when I can and feeling guilty about taking time out of the office, I now schedule walks and time outside into my day. It is as important as a meeting with colleagues or research for a project because it enables me to be a better colleague and more productive employee.

I feel many of you reading this will identify with this sentiment. Now more than ever, in the midst of COVID-19 when we must shelter in place and thereby limit our access to green spaces,we have collectively become more aware of just how important nature is to our mental and physical wellbeing. Maybe we took it for granted before all this? Maybe it is a case of only when something is taken away do we acknowledge its true value? We must not forget there are communities and fellow citizens that cannot access green spaces regardless of a stay-at-home order. The sad reality is that being able to access and benefit the healing beauty of nature is still a privilege not afforded to all.

So, I for one would love to think that after all this has passed and we can once again move around more freely, that as a society we will place a higher value on nature, public green spaces, trees, plants, and our deep-rooted connectivity with it. I hope that a greater value will be placed on ensuring nature and green spaces are accessible for all in all senses of the term. And that we collectively will have a greater appreciation for the concept of biophilia … that we all instinctively and genetically need to affiliate with nature.