Every garden tells a story. At Longwood, our gardens tell of horticulturally-inclined Quaker twins Samuel and Joshua Peirce who in 1798 began planning the arboretum that stands today as Longwood’s Peirce Park; industrialist-turned-Longwood-founder Pierre S. du Pont who purchased the property to save its trees; and the plants and people who carry on their collective legacy by way of Longwood’s horticulture, education, and the arts.

As you stroll the grounds, you may find yourself transported to a chateau in France, a villa in Italy, or the Amazon rainforest. In the Conservatory, you can find orchids whose names tell a fascinating story about language, and soon, thousands of carefully nurtured and trained plants on view during our annual Chrysanthemum Festival that tell the story of our dedicated horticulturists and an ancient Asian art form that we are proud to perpetuate. As the docent intern at Longwood, I focus on how we interpret and share such details, so I am constantly thinking about the stories we tell in our garden, as well as the design choices, gardening techniques, and plant selections we employ to tell them.

I started my internship in early June, and since then, I’ve learned so much about the distinctive blend of extraordinary plants, excellent garden design, and compelling history that makes Longwood special. I’ve also had the opportunity to visit six other public gardens in the area—and counting—with my intern class on our weekly Thursday field trips. We are often fortunate to both receive a guided tour and have some time to explore on our own to learn what makes each garden unique—and see for ourselves what stories they have to tell.

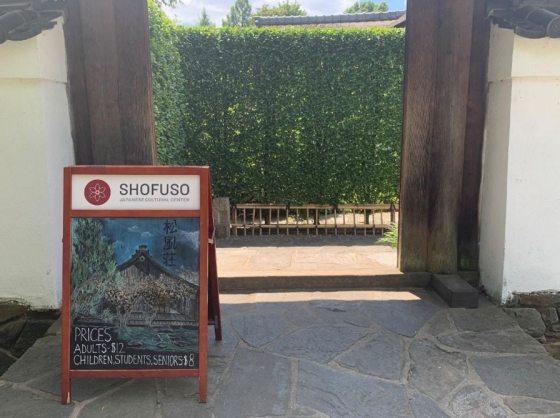

In August, 14 of us traveled to Fairmount Park, the site of Shofuso Japanese House and Garden. We walked down an asphalt path, then stepped over a wooden threshold built into an impressive stone wall and instantly sensed we’d entered a space very different from the bustling city outside. Shofuso’s head gardener, Sandi Polyakov, greeted us, guiding us to a cubby where we’d take off our shoes before following him into the house. Inside, the sliding doors were pulled shut and we knelt on tatami mats and listened as he told us a bit of the story of the house and garden.

The house at Shofuso, we learned, is representative of an early style of Japanese architecture called shoin-zukuri. In this style of architecture, the house is specifically designed to frame the view of the garden, and the garden is, in turn, designed to be viewed from a seated position within the house. From this seated position, the garden takes on the appearance of a paneled landscape painting. So, we sat and viewed the garden from the floor. Some of us listened intently as Sandi shared stories of the ancient Japanese symbols reflected in the garden before us, while others drifted in and out between listening and observing, leaning into the purpose of the viewing garden, which as Sandi shared, is “primarily for contemplation, where ponds may represent vast oceans, and the various stones, islands, and plantings symbolize lands of paradise which can only be reached by journeys of the mind.”

Once we’d completed our journeys of the mind, we stood and readied ourselves for a journey around the side of the house to the tea garden. The tea garden, unlike the viewing garden, is a journey of the body, grounded in the stones, plantings, and paths one interacts with on their way to the tea house. Sandi’s description of the tea garden said it all: “Deep greens and mosses create a subdued atmosphere, where showy flowers and scents are avoided so as not to distract from subtler moments. Plants are pruned to enhance the wild structure and to create opportunities for light and unique shadows to play in the breeze. Even the stepping stones are purposely set slightly askew, in seemingly haphazard arrangements, to induce slow, careful passage. If the viewing garden is a timeless musing into the beyond, the tea garden is very much a setting of the now, for the now.”

One of the most poignant stories from our trip to Shofuso is that of the doorframe of the tea house. Sandi told us the low doorframe was designed to ensure that all who entered had to bow, from the most powerful shogun to the humblest servant. The tea house is the great equalizer. We learned this firsthand as we each stepped through the doorway, bowing our heads as we passed over the threshold. (Okay, I won’t lie to you, a couple of our interns made it through without bowing. I guess if you’re short enough, you catch a break from the metaphor.)

Would we have caught on to the story if Sandi hadn’t told us? Who knows. I kind of like to think our bodies would have picked up on it, our bent necks would have spoken to that instinct within us that searches for story, shaped by the countless stories we’ve been told throughout our lives, and the stories that shaped us before we were born.

Who tells the story of the garden? Is it the landscape architect, in writing or in conversation with others, or is it the gardener with their tools, pruning a tree to create a view that they hope will tell the story they want to tell? Is it the docent, leading a tour, or the interpretive signage on stanchions sticking up from the ground? Is it the viewer in conversation with a friend, or is it the garden itself? Who’s to say? Maybe it’s a little bit of everything.

Now, back in my house on The Row at Longwood, a teacup decorated with cats and Japanese characters sits on my counter and tells part of the story of my trip to Shofuso. I go into our Gardens and think about the stories told by the designs and plantings here, the feelings evoked by the strong, bright color blocking along Flower Garden Walk, the story told by the bluebirds as they flit through the Meadow. Gardens are rich with stories, and they whisper to us whether we listen for them or not. Next time you’re in the Gardens, take a moment. What do you hear?