The newly renovated and reopened Orchid House, with its hundreds of carefully curated orchids, is an undeniable place of beauty. It’s also the physical representation of Longwood’s dedication to the role that orchids play not only at the Gardens as a unique source of beauty and diversity, but around the world as a symbol of conservation. In support of these ideas, Longwood developed its Orchid Conservation Program in 2015 to ensure that a variety of orchid species are saved for generations to come. Our research and conservation efforts exist not only to build upon our world-class collection of Conservatory orchids, but to advance orchid conservation on a global scale. Our dedication to orchid conservation is expansive and unwavering—but why do we go to such lengths to conserve them?

Orchids occur on every continent (except Antarctica) and make up a staggering 8 to 10 percent of the total diversity of all plants. Despite their global prevalence, all orchids are considered endangered, as their populations are generally rare and declining in the wild. This is alarming because they are also critically important in determining the overall health of ecosystems worldwide. Public gardens, universities, and institutions around the world work in orchid conservation, yet few public gardens are directing their research holistically, from the field work and seed collection that begins the process, to original research to conservation initiatives, to the restoration of native orchid populations using seedlings raised in the laboratory. Here at Longwood, our long-term conservation efforts started with native orchids in Pennsylvania and serve a vital role. Although they are valuable contributions to science, many academic research projects studying orchids can be limited in time and scope, necessitating a holistic approach to orchid conservation, such as ours, that involves aspects of horticulture, ecology, and other fields of plant science with the potential to span decades, or even centuries.

Our work to conserve orchids takes place not only in the laboratory, but also in locations around the globe. Since 1956, we have partnered with public gardens, botanical institutions, and universities from around the world to find, collect, and trial new plants through plant exploration. Over the years, this program has evolved from traditional plant-finding expeditions, to homing in on specific plant targets, to advocating for conservation of plant resources in the countries explored. Using knowledge we developed researching native orchids, we have started to apply our scientific expertise to orchid conservation on a global scale, working with partners around the world to assess rare orchid populations and to help develop conservation plans for them.

As a corollary to our plant exploration program, our Orchid Conservation Program was formalized in 2015 (but really dates back to when our founders Pierre and Alice du Pont purchased their first native orchid in 1923). We have used original research to develop innovative and sustainable techniques to grow large seedling populations of native orchids for the purpose of restoring orchid populations native to Pennsylvania, the mid-Atlantic region, and across the country, while building beautiful, hardy, and genetically diverse orchid collections in the gardens. To date, we have made approximately 360 seed collections of 110 of the approximately 220 orchid species native to North America, including 41 of the 60 species native to Pennsylvania, and in turn have restored native orchid populations using seedlings raised in our laboratory.

A group of orchids we are particularly interested in are the fringed or bog orchids of the genus Platanthera. They are among the most beautiful orchids native to Pennsylvania and while some, such as the state-endangered Platanthera blephariglottis, are relatively easy to propagate in our laboratory, others, such as the threatened Platanthera peramoena, are among the most difficult native orchids to propagate.

Working with partners in Pennsylvania, we were able to develop a study in which we systematically tested the germination potential of seeds collected from the plants at different times. To our surprise, we found that this made a huge difference in our ability to propagate this species. We went from not being able to germinate the seeds at all, to germination rates of more than 90 percent when we collected the seeds at 25 days after pollination instead of 50. Many are surprised to hear that native orchids cannot only withstand cold temperatures, but actually need them in order to survive.

Therefore, native orchids are not normally displayed in our Orchid House, but can be seen in our outdoor gardens here at Longwood, specifically in Peirce’s Woods, the Hillside Garden, and Forest Walk, where they bloom in late spring and summer. A total of at least seven native orchid species, both natural and cultivated, can be found here in our outdoor gardens—these terrestrial orchids survive outdoors year-round and more will be added in the coming years. One of the most dramatic native orchids to be found in the gardens is the globally rare Kentucky lady’s slipper (Cypripedium kentuckiense). This species can be found growing in Peirce’s Woods and the Forest Walk, where they flower in late May. It takes three to five years to grow lady’s slippers orchids from seed to flower, and while this may seem slow, it is interesting to note that if everything goes to plan, they can live for hundreds of years! A 1963 planting of the large yellow lady’s slipper in the Hillside Garden serves as a testament to their longevity.

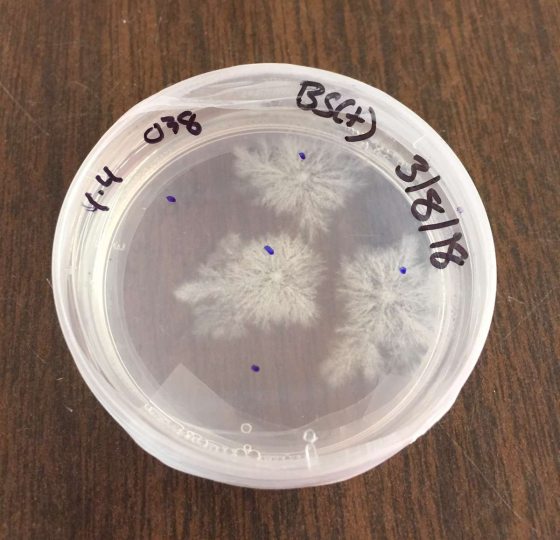

In the wild, mycorrhizae are critical to the survival of orchids. Mycorrhiza, which means “fungus roots,” is an association between a fungus and a plant’s roots. In some cases, the relationship is mutualistic, in that both the plant and the fungus obtain something from each other. In the case of orchids, however, the plants actually parasitize the fungi and use them as a food source both while the seedlings are developing and as adult plants. We are trying to better understand these relationships and apply them to the cultivation and conservation of native orchids. To support this line of research, we have established an orchid mycorrhizal fungus bank.

Orchid mycorrhizal fungi can be extracted from the roots of wild adult orchid plants (without harming them!), grown in the laboratory, and maintained in vitro for later use. To date, we have worked with 20 taxa of orchids under this effort, and there are fungi from 10 taxa of orchids in our fungus bank. Initial experiments with inoculating orchid seedlings with fungi show promising results for growing the more challenging orchid species. Currently, we are focused on obtaining the orchid mycorrhizal fungus associated with Galearis spectabilis, a native orchid that was one of Pierre S. du Pont’s first recorded purchases. We have yet to successfully grow this species in the laboratory, but the fungus could hold the key to a breakthrough.

These efforts are just the tip of the iceberg regarding our orchid research and conservation efforts. We will continue to evolve and expand upon conservation initiatives through plant exploration; seed propagation and banking; original research projects; ex situ and display collections development; and development of conservation partnerships. These initiatives have allowed us to develop expertise with native orchids in our own backyard that can impact regional, national, and global orchid conservation for many generations to come.