The plant records system has been the backbone of plant documentation at Longwood Gardens for decades. Since 1955 all orchids in our collection have been accessioned and their life status tracked in a system whose “record will be of information and great value for our program of public education,” as was reported to our Board of Trustees in October 1955. Throughout the years, the system has allowed us to know the make-up of our renowned orchid collection, but given real-time changes in our collection, has proven challenging and shown us the need to update our approach.

At the center of our plant records system is the accession number, an eight-digit code that indicates the year of that plant’s acquisition and a four-digit sequential number. When our plant records system first began in 1955, assigning the accession number was done in paper log books and paper accession cards. More recently, beginning in the 1990s, these assignments are made via a computer database. The assigned accession number ties the plant with information such as the scientific name, when it was received, from where it was received, and how many plants were received. The location of the plants is also noted. Today, more than 65,000 accessions have been recorded in the plant records database, with thousands more recorded in our archival log books.

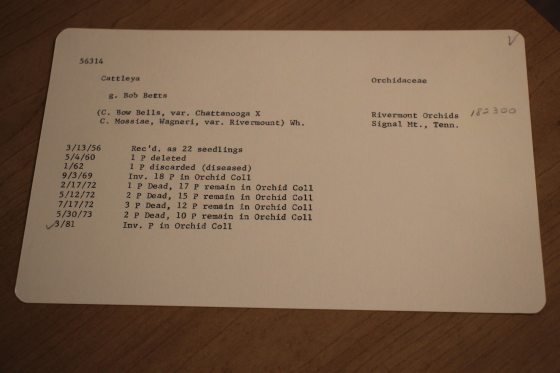

Historic plant records accession card for Cattleya Bob Betts, 1956-0314, last annotated March 1981. Currently there are six plants of this accession living in the collection. Photo by Kristina Aguilar.

After the accession number was assigned, each pot would then receive a brass accession tag, indicating its accession number. Through the years, plants have been divided—which in turn makes more pots of an accession—and some have died, making less of an accession. Given these changes and the fact that we are keeping track of living things, the accounting—a real-time number of plants within an accession and therefore the entire collection—was hard to determine.

Cattleya orchids growing in one of the former orchid growing houses, 2020. Photo by Yovenn Peignet.

Fast forward to March 2021, when the western Conservatory greenhouses, including the orchid growing houses, needed to be emptied of plant material and the plants relocated for the start of Longwood Reimagined. The orchid collection, some 5,000 plants, needed to move to their new home in the lower production greenhouses.

When preparing to move the collection, we realized that all the orchid accession records’ current locations would need to be changed in the database to reflect the plants’ new physical location. We also knew that we didn’t have a current number of plants recorded within each accession, given those challenges previously outlined. Therefore, moving this large collection became the perfect opportunity to inventory and add a secondary identifier to each orchid—a barcode—so the specific location of each pot could be tracked. Each barcode would give each plant a unique identity.

Having a unique identity is very helpful when keeping track of an inventory and knowing the make-up of a collection, but in terms of the overall health of the collection, tracking individuals is an important element of correctly identifying and eliminating any plant disease.

Cart of virus-negative plants ready for display in the Orchid House. Photo by Kristina Aguilar.

In 2016, Longwood started to test each individual orchid plant for virus. When we examine orchids for viruses, there are two viruses with which we are primarily concerned: Cymbidium Mosaic Virus (CymMV) and Odontoglossum Ringspot Virus (ORSV). The viruses typically present in orchids will not kill the orchids outright, but will weaken the plants and potentially impact the flower display. The virus also makes the orchid more susceptible to other pests, diseases, and abiotic stressors.

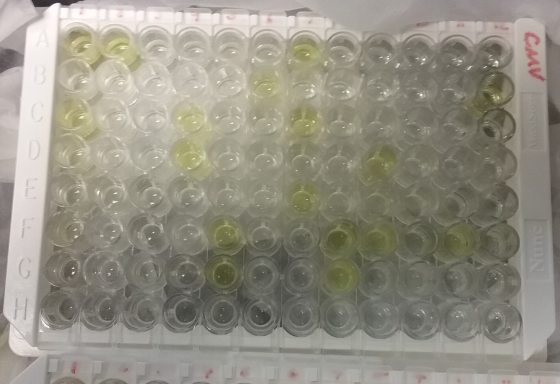

For our virus testing, we use enzyme linked immunosorbent assay tests, or ELISA, conducted in our Integrated Pest Management lab. This two-day-long testing process works by detecting the antigen produced by the virus within the plant tissue. A sample of the plant is taken following appropriate sanitation protocols to ensure we aren’t cross contaminating our samples. That sample is then cut down to size, ground up, and placed in the ELISA plate, where it goes through a series of incubations and additions of different buffers.

If the virus is present at the end of the process, the sample and the components of the different buffers will have bound together, resulting in a color change in the well. We can test 94 samples per test plate, plus a positive and negative control to ensure the efficacy of our test. If the positive control is positive and the negative control is negative, you can trust the results of your test.

Completed ELISA test for Cymbidium Mosaic Virus. In this test, the first two cells in row one (A and B) show the positive and negative control. As long as A1 is yellow and B1 is clear, we can trust the results. In the rest of the wells, the yellow indicates the presence of virus. Photo by Beth Pantuliano.

When each plant is tested for virus, a four-digit virus number is recorded. Upon completion of the testing, the results (either positive or negative for virus) is recorded with the virus number. To date, we have tested 5,240 orchids for virus. So how do we manage a collection with both virus-negative and virus-positive plants?

Designated wagons designed to carry virus-negative and virus-positive plants separately are used to transport orchids between the growing houses and Conservatory display. Photo by Kristina Aguilar.

The plant records system is the perfect place to store all of the plant’s information, including the original accession information and the virus test number and its results. In December 2020, barcoding the individual orchid pots began. Barcoding began after virus testing started; because the orchids had an accession number and a virus number, the thought to add a barcode to easily scan and get both numbers and therefore both groups of information (accession and virus info) was the solution. It was decided that since we knew from the virus test number whether a plant was virus- positive or -negative, this would determine the color of barcode label the plant would receive. Silver tags would go on the virus-negative plants and red tags would go on the virus-positive plants. The color of the tag gives a fast, readily identifiable diagnosis to the plant, and helps staff and volunteers maintain the system of separation that has been implemented in the greenhouse. Virus- positive plants have dedicated locations (benches) in the growing greenhouses to keep them separated from the virus-negative plants. Both virus-positive and -negative plants are safely displayed together but transferred to the Conservatory in separate wagons.

A silver barcode tag indicates that this Cattleya milleri, 2015-0848, is virus-negative. Photo by Kristina Aguilar.

To date, 4,369 orchids have received barcodes, and we continue to work on barcoding the remainder. Scanning the barcode brings up the plant’s record in the database. From there, staff can change the plant’s location (from growing house to Orchid House display for example), can note whether the plant is flowering, or can deaccession the plant if necessary. By combining the efforts of three divisions at Longwood— Floriculture, Integrated Pest Management, and Plant Information and Mapping—the historic orchid collection, started and beloved by our founders Pierre and Alice du Pont, will flourish and will be well-documented and cared for far into the future.