Many horticultural and aesthetic decisions go into achieving the true goal of bonsai: nurturing and training a tree in a container to appear as it would in nature. One such decision—and one that encompasses both horticultural and aesthetic considerations—is determining which style a bonsai should follow. In nature, trees grow in a variety of styles—consider the upright style of a redwood tree versus the cascading foliage of a willow tree, for example. The way in which a tree grows is often determined by their environment, and as a bonsai artist, I look to honor that environment, and the way in which that tree would grow in nature, when determining how to shape and style a bonsai. Those decisions and determinations can be seen firsthand when viewing the variety of bonsai we have in our new bonsai display near the Green Wall in our Conservatory.

The centuries-old Japanese art of bonsai originated in China as the practice known as penjing, or the art form of creating landscape scenes on a miniature scale. Throughout the years, many styles to classify bonsai trees have been developed to closely resemble circumstances in nature. These styles, however, are not hard and fast rules, but open to personal interpretation and creativity, meaning that bonsai trees do not need to conform to any particular style. The styles exist, however, to help serve as guidelines when shaping a tree and honoring its natural environment.

It's possible that bonsai can be trained into different shapes throughout their lifetime. Sometimes artists restyle a bonsai simply because of a changing of hands between the previous and current artist; sometimes a style needs to change because, for example, a branch dies and the tree’s composition needs to be rebalanced.

Just as styles themselves are open to personal interpretation, so are the groupings and definitions of bonsai styles—in fact, there’s much variation among bonsai artists in just how many bonsai styles really exist. Many subscribe to the belief that there are five basic bonsai styles, each derived from the tree’s angle of growth from a container.

The first of these five basic styles is known as formal upright or Chokan. The formal upright style is considered the most common of bonsai styles and follows the tree’s natural design in an upright growing manner. Many formal upright trees in nature grow in an open location without much competition for light. The trunk line is perfectly straight and vertical, with the apex (or top of the tree) located over the center of the trunk base; the trunk must also taper from base to apex, meaning its thicker at the bottom, then thinner as it goes up. To achieve a tapered trunk, the bonsai artist must make a series of cuts to the apex. The apex is cut off and an adjacent thinner lateral branch is oriented or wired upwards as the new top. This process is continued multiple times over many years. Each branch is shorter than those below it.

This pomegranate (Punica granatum) is also of the formal upright style. Pomegranates naturally have a twist to their trunks. The interaction between the twisting live wood and deadwood offers a dynamic feature within the upright style, as upright is the most stable and balanced of the styles. Photo by Carol Gross.

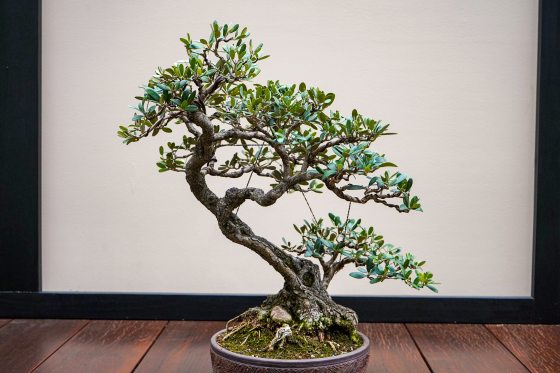

The second of the five basic bonsai styles is known as informal upright or Moyogi. This style depicts a tree in nature that has been affected by the elements, such as wind—with those effects shown in its a non-linear trunk line in contrapposto, meaning the main trunk goes one way and the apex returns back to the center over the top of the base of the tree; it’s an asymmetrical balance like what you would see in a contrapposto pose of the human figure. This style is very common in both nature and in bonsai. The tree must also have a central location in the pot. To achieve informal upright style in bonsai, one can create movement through the use of wire, or can start with a tree that already shows such effects of nature.

The informal upright style can be seen in this olive (Olea europea ‘Manzanillo’). Originally designed as a semi-cascade tree, this tree is currently in development. The tree was repotted and the main trunk line now orients more vertically. The apex is currently being trained with wire to move back towards the base. Photo by Carol Gross.

Slanting style or Shakan refers to trees that have tilted to one side, often as a result of wind or water in one dominant direction or by the tree reaching for sunlight. As the tree slants, it develops a well-developed roots system on one side so the tree can remain standing. While the trunk can be slightly bent or very straight, it still must be thicker at the bottom than at the top. When it comes to the branches, the first branch must grow in the opposite direction of the tree, so the overall tree achieves visual balance.

This Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii ‘Kotobuki’) is of slant style—the apex is over the edge of the container and is pointed the same direction as the main trunk line. Photo by Carol Gross.

Cascade style or Kengai is true to a tree on steep cliff that bends downward, resulting from such factors as falling rock or snow in nature. In bonsai, cascade style trees can be planted in tall pots, or more often in a shallow container with a stand, to maintain their direction of growth—which is opposite to a tree’s natural growth toward sunlight. Cascade-style bonsai grow upright for a small bit, but then cascade downward—but must never touch the surface on which it is displayed.

True to cascade style, this Juniperus procumbens ‘Nana’ as shown our nursery, grows beyond the bottom of its container. This juniper has been trained in the cascade style since 1966 and came to Longwood in 1968. Photo by Carol Gross.

Semi-cascade style or Han-Kengai is also representative of trees found in nature on cliffs or banks. Just like cascade style, these trees feature a trunk that grows upright for a bit and then bends downward beyond the rim of the container or perhaps sideways. Differing from the cascade style, however, is that a semi-cascade trunk never grows below the base of its container.

This Silverberry (Elaeagnus pungens) serves as an example of the semi-cascade style. I have since repotted this tree at the angle in which I’m holding it. Photo by Carol Gross.

A number of additional bonsai styles are considered modifications of the five basic styles. For one, broom style pertains to a straight, upright trunk, along with branches and leaves that form a radial crown at the top. This is a common style seen in many deciduous trees in our region.

The broom style is suited for deciduous trees with fine branching, such as this Japanese zelkova (Zelkova serrata). This style is achieved by growing a trunk upright and then trunk chopping it. At the cut site, new growth emerges from the same location and the tree is wired into a broom form. Photo by Carol Gross.

The broom style is also known as a flame style, particularly for ginkgo—such as this Ginkgo biloba—in which the branch formation is less lateral than a traditional broom style. Trees in the flame style often don’t have defined pads, as do trees in the broom style. Photo by Carol Gross.

The literati style or Bunjingi reflects trees found in densely populated areas in which a tree tries to grow taller than all of its counterparts in order to thrive. The trunk grows crooked as it grows upward, and does not feature branches as the sun can only hit the top of the tree. In many cases, trees in the literati style feature very delicate trunks with a lot of movement. Many types, the apex is off-centered.

This hinoki false cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa) is of the literati style. The more dynamic the interaction between the live and dead wood the more valued the tree. Notice the movement of the trunk, not only from left to right but from front to back. A sinuous trunk movement that has visual interest from multiple angles is desired. Photo by Carol Gross.

The forest style or Yose-ue is made up of three or more trees planted in a natural, staggered pattern resembling a forest. Trees of different heights are arranged at different distances from one another. The overall effect resembles a forest canopy. Traditionally taller trees have been placed in the front and center with smaller on the sides and back. This aesthetic has shifted with contemporary bonsai. Asymmetrical forest design with tall trees at multiple points is now being explored, with the smaller trees in the back or on the sides giving the illusion of depth.

This loose-flower hornbeam (Carpinus laxiflora) forest serves as an example of the forest style. Photo by Carol Gross.

The raft style or Ikadabuki emulates a tree that has been blown over in a storm. The tree’s roots then develop from the resting trunk and the remaining branches grow to resemble new trees still connected to the old trunk and all from the same root system. To achieve this style in bonsai, a tree is potted horizontally and the side branches become the new vertical leaders of the tree. Then the branches are styled like a forest design with dominant and subdominant apexes. With both raft and forest design, multiple tree heights, trunk thicknesses, and a three-dimensional approach (non-linear) planting is desired for a natural look.

This raft style bonsai was originally an upright tree. It had multiple flaws in its design and the tree would have to be started over completely by removing all the branches to improve the design. It was naturally fit for a raft style and its inherent features were utilized. Photo by Carol Gross.

Come see these bonsai styles for yourself in our new bonsai display near the Green Wall in our Conservatory. We regularly update the bonsai on display, so you’ll be treated to a variety of styles—but constant bonsai beauty.