As part of the Longwood Fellows Program, Fellows spend two months with partner organizations around the world to immerse themselves in their host’s culture, learn from thought leaders, and share and grow their own expertise. Here, our Fellows reflect on lessons learned and beautiful memories made during their time in New Zealand, Georgia, Ohio, England, and California.

Nathan Anderson

Auckland Botanic Gardens (Auckland, New Zealand)

Before I ever stepped foot in Aotearoa New Zealand (Aotearoa is the Māori word for “land of the long white cloud”) for my field placement, I had been told of the culture of New Zealand’s public gardens and how Kiwis were not inclined to pay for a horticultural experience, particularly when the entire context of living on this island paradise is one of lush greenery and endless majestic vistas. Free and open to the public with 1.2 million visitors a year, Auckland Botanic Gardens (ABG) is visited by many seeking a leisurely park experience. The staff see this as the critical opportunity to highlight the benefits of horticulture and ecological sustainability to a diverse audience already on-site.

Indeed, there are amazing plants and landscapes at every turn in New Zealand: at Auckland Botanic Gardens (the Rock Garden and its aloe collection emerged as one of my favorites—as shown as the first image of this blog post), at countless other Auckland gardens and parks, along roadside vistas, amidst the volcanic terrain and endless beaches, and points beyond. The breadth and depth of the plant variety I experienced was overwhelming. I was the proverbial kid in the candy store, except I knew so few of the sweets by name. I soaked up the eye candy just the same.

Taking ABG’s motto “Where Ideas Grow” to heart, I embarked on immersing myself in how a public garden on the other side of the world operates and engages. As a public institution under the jurisdiction of the Auckland Council, ABG has no gate and is never truly closed. I quickly learned how the reality of porous borders informs and challenges the garden’s people and resources. The staff is responsible for an immense public property and undertakes a vast array of initiatives like thoughtful and compelling programming, public and reserved events, and most importantly, diverse horticultural collections and conservation efforts.

Tororaru (Muehlenbeckia astonii) hedge—an ABG "Star Performer.” Photo by Nathan Anderson.

ABG leadership starts with Manager Jack Hobbs, who has a tenure of more than 40 years with the Gardens. He sets the tone for the organizational culture and can-do spirit evidenced throughout the gardens, programs, and place in the community. For example, when a 1990s-era public survey that found the community thought of the Gardens as a “nice place to feed the ducks,” Hobbs pivoted community engagement to promote ABG as a resource for home gardeners and a universal place to engage people with plants, where visitors also could learn something about horticulture, ecological systems, and the environment—either incidentally or comprehensively through numerous interpretation modes. Programs such as Star Performers and Plants for Auckland highlight species through garden signage and online and printed literature explaining why these highly recommended plants are encouraged for home landscapes.

From left: Wintergarden Site Manager Jonathan Corvisy, Manager Jack Hobbs, and Longwood Fellow Nathan Anderson at Auckland Domain Wintergarden. Photo provided by Nathan Anderson.

From this pivot, ABG’s mission emerged to be “a spectacular South Pacific Botanic Garden that is widely recognised for its outstanding plant collections, Auckland regional identity and the interest inspired in the community.”

I see the last point of the mission statement regarding community inspiration as the common thread for ABG operationally and experientially. Building on a consistent audience with many visitors who are not necessarily “plant people” creates an open pipeline for education and the expansion of thoughts about sustainability, green infrastructure, resource protection, and ecological horticulture. A fully engaged and fiscally-sound Friends of the Auckland Botanic Gardens volunteer group is a critical piece of ABG’s community engagement success story. Their activities have supported both significant capital projects and ongoing staff development by sponsoring employees’ attendance at conferences and educational opportunities domestically and abroad. Community partnerships create events like Eye on Nature, an annual week-long program for 1,200+ schoolkids, where green partner organizations set up educational environmental activities throughout the garden. I chaperoned one of the student rotations and was captivated by the students’ enthusiasm as they bounded between each outdoor classroom, witnessing the seeds of environmental stewardship being sown.

Working alongside Visitor Services Manager Micheline Newton and Curator and Longwood Fellow alumna Barbara Wheeler, I was fortunate to contribute to various projects, including the latest market research efforts for the next five years of programming and events; planning for the next Sculpture in the Gardens, a bi-annual competitive public art exhibition with major works sited throughout ABG; and the formalization of presentation guidelines for the horticultural team.

From left: Longwood Fellow Nathan Anderson, ABG Curator and Longwood Fellow alumna Barbara Wheeler, and ABG Visitor Services Manager Micheline Newton in the Potter Children’s Garden. Photo by Nathan Anderson.

I also met with Auckland Council’s master planning department to discuss the development of the last remaining four acres of land adjacent to the Gardens. This recent acquisition by ABG is eyed for a traditional Māori garden, with hopes of engaging local Iwi (tribes) to collaborate on the design, implementation, and ongoing maintenance of this initiative.

This project will be a highly visible example of how ABG integrates Auckland Council’s Māori Outcomes framework, adopted in 2021, which addresses well-being by focusing on the Council initiatives that matter most to indigenous populations. The Gardens’ connections with native plants are a direct vehicle for engaging Māori on the land, and this initiative will provide opportunities for both engagement and workforce development. Observing these dynamics led me to draw parallels to the work we have begun at my home institution and across the United States to acknowledge the impact of colonialism on indigenous communities and the steps that can be taken to mediate that history into positive change today.

Beyond ABG, I was able to traverse both the North and South Islands, visiting a wide range of botanic gardens and public estates. This included members of Botanic Gardens of Australia and New Zealand (BGANZ) such as Christchurch Botanic Gardens, Dunedin Botanic Garden, and Hamilton Gardens.

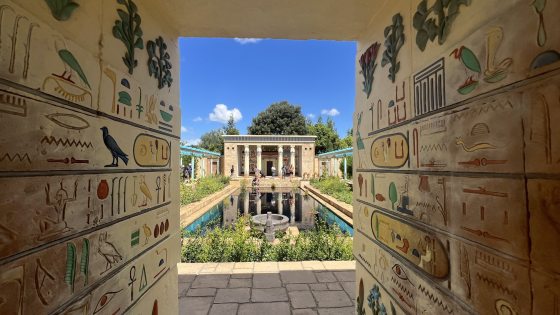

Ancient Egyptian Garden at Hamilton Gardens. Photo by Nathan Anderson.

The New Zealand Gardens Trust (NZGT), a community of garden enthusiasts, is a clearinghouse for finding landscape gems. An NZGT garden is assessed to a standard identified for the public through a star rating system. The Trust offers a curated selection of 109 gardens, each showcasing a unique blend of subtropical plants, native flora, and traditional settings. Highlights of my many visits included Ayrlies Gardens & Wetlands, Ohinetahi, Larnach Castle, and The Giant’s House (I encourage you to look up more about each of these landscape jewels). Another highlight was a visit with Dr. Keith Hammett, an internationally renowned Dahlia breeder. I had the opportunity to tour his Auckland gardens and hear of his life’s work bringing the now-ubiquitous species from Mexico to the world in its myriad beloved varieties.

Aotearoa New Zealand is highly concerned with ecological sustainability. They have implemented significant biosecurity efforts, particularly at the border, to protect their island nation from invasive non-native species. One limitation of this approach is that any non-native plant species in current collections would be nearly impossible to procure again, so the ongoing viability of existing specimens is highly important. Thus, in-house propagation and in-country partnerships are key to maintaining diverse plant collections in botanic gardens. ABG is highly involved in this work.

I was invited to participate in a seed-collecting expedition to Harekare Beach with Auckland Council’s Senior Regional Advisor on threatened species Emma Simpkins; ABG Botanical Records and Conservation Specialist Ella Rawcliffe; and ABG Propagator Owen Nelson. We went on the hunt for spike sedge (Eleocharis neozelandica), a regionally critical plant that Simpkins had observed in this particular area previously. While I was of minimal help in locating this tiny species, the team successfully harvested seeds that Nelson will in turn propagate. This Council-ABG partnership leverages ABG’s expertise and facilities to sustain threatened species populations by adding them to ABG’s collections and by reintroducing them to suitable native habitats outside the Garden.

The rich and diverse ecological experiences, learning opportunities with so many garden leaders, and cultural traditions of New Zealand combined to provide a truly memorable field placement journey. The people, plants, and places are imprinted in my heart. I am so grateful for everyone who contributed to this adventure, and I look forward to one day again visiting the horticultural wonders of the “land of the long white cloud.

Edem Kojo Doe

Atlanta Botanical Garden (Atlanta, Georgia)

In early February I arrived at the renowned Atlanta Botanical Garden (ABG), a 30-acre urban oasis in Midtown Atlanta, with a lot of enthusiasm and hope of delving deeper into the day-to-day operations of this beautiful garden.

While at Atlanta Botanical Garden, I expected to shadow the staff in each of the Garden sections, giving me the opportunity to see and learn how all the different departments approach their work. My experience surpassed my expectations as I made lifelong friends and colleagues, shared ideas, and saw how collaborative leadership both internally and externally can align stakeholders across an organization to achieve set goals and targets.

I divided my time at ABG between their locations in Midtown Atlanta and Gainesville. I was impressed by how both campuses function and how different they are in their size and living collections. The Midtown Fuqua Conservatory and Orchid Center, for one, houses rare tropical and desert plants from around the world, and it is the largest orchid center in the United States. The Gainesville location extends ABG’s operations into the North Georgia landscape and boasts the largest conservation nursery in the Southeastern United States.

ABG’s work and impact travel beyond its garden walls and the city of Atlanta. One of my key takeaways from ABG was the pivotal leadership role played by the Conservation and Research Department, as well as the International Plant Exploration Program, in promoting ex-situ and in-situ conservation efforts on a global scale through effective collaboration. The significance of collaborative leadership cannot be overstated when it comes to ensuring successful plant conservation and stewardship worldwide.

From left: Manager of the International Plant Exploration Program Scott McMahan and Longwood Fellow Edem Doe at the Plant Evaluation Nursery, Atlanta Botanical Garden, Gainesville location, where plants are evaluated for their suitability for the region. Photo by Tim Marchlik.

ABG’s Vice President for Conservation and Research Emily Coffey, Ph.D., embodies exemplary leadership. By expanding her team from four to 30, she has curated an impressive collective of scientists and researchers to spearhead the fight against extinction for key rare plant species. Through ABG’s Southeastern Center for Conservation, their endeavors are safeguarding critical endangered flora with a particular emphasis on Sarracenia, or Pitcher Bog Plant, an imperiled southeastern plant species.

Dr. Coffey’s style of leadership fosters collaboration and innovation among her team members. She equips them with essential resources and tools to conduct their research effectively while empowering them to take ownership of their projects. This approach not only resulted in augmented personnel but also culminated in significant breakthroughs for plant conservation. Under her guidance, ABG’s Southeastern Center for Conservation has established itself as a prominent institution dedicated to preserving rare plant species, attracting researchers and scientists worldwide to collaborate on groundbreaking initiatives.

I had the opportunity to witness firsthand how a garden can be activated through educational programming, incentivizing people to interact with nature. I collaborated with ABG Senior Manager of Youth Programs Kathryn Masuda to lead a workshop on plant anatomy for students and teachers from Atlanta’s Title I schools. I also participated in the “Sprouting Scientists and Garden Playtime” event hosted by ABG in partnership with the Atlanta Science Festival, in which the Education Department used seeds of major food staples and flower dissection exercises to identify different pollinators found within the Garden’s ecosystem. For my part, I taught visitors about creating habitats for local wildlife within their own gardens, while emphasizing the importance of providing adequate food sources, shelter, and water for animals such as birds and butterflies. This experience was highly rewarding; it inspired participants’ newfound appreciation for nature and a desire to make positive contributions toward their communities.

My experience at ABG showed me how educational programs about gardening can profoundly impact both individuals and entire communities. It has further motivated me to explore ways of utilizing gardening techniques to promote environmental awareness alongside sustainability initiatives.

From left: ABG Family Programs Coordinator Allison Pratt and Longwood Fellow Edem Doe at the Children's Garden. Photo provided by Edem Doe.

Perhaps the most important lesson I learned was how critical adaptability is within a constantly changing environment like a botanical garden. Extreme weather conditions or staffing issues can pose significant challenges and require quick adjustments without compromising the quality of the guest experience.

Longwood Fellow Edem Doe at the Gainesville campus of ABG. Photo provided by Edem Doe.

While in Atlanta, I also had the chance to engage with other leaders through local horticultural and cultural networks. Longwood Fellow alumna Abra Lee (’20) connected me with leaders in the arts and garden world. This included an invitation to dinner at the French Consulate in Atlanta, where I met artists, government officials, nonprofit leaders, and influencers from Georgia. I was introduced to prominent figures within the gardening world, who generously shared their expertise on managing both people and plants. I concluded my time in Atlanta with an invitation to attend an MLS soccer game between Atlanta United and Chicago Fire. The ambiance and anticipation at the Mercedes-Benz Stadium were electrifying and the energy was infectious.

From left: Longwood Fellow alumna Abra Lee, Consul General Ann-Laurie Desjonqueres (representing France in the states of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee), and Longwood Fellow Edem Doe Longwood Fellow at the invitation of the French Consulate for dinner. Photo provided by Edem Doe.

Overall my field placement in Atlanta proved invaluable, offering insights into effective organizational management under expert guidance amidst breathtaking surroundings. It was a truly unforgettable adventure!

Muluken Nega Kebede

Holden Forests and Gardens (Kirtland/Cleveland, Ohio)

When I chose Holden Forests and Gardens (HF&G) for my field placement, my objectives were to actively contribute to the organization’s strategic planning process, advance revenue-generating efforts, and utilize plants and horticultural assets for long-term philanthropic revenue campaigns. I was especially interested in working with a unique public garden that formed from the merger of two separate organizations—Holden Arboretum and Cleveland Botanical Garden—and that also recently welcomed a new CEO, and I anticipated a comprehensive learning experience aligned with my professional goals.

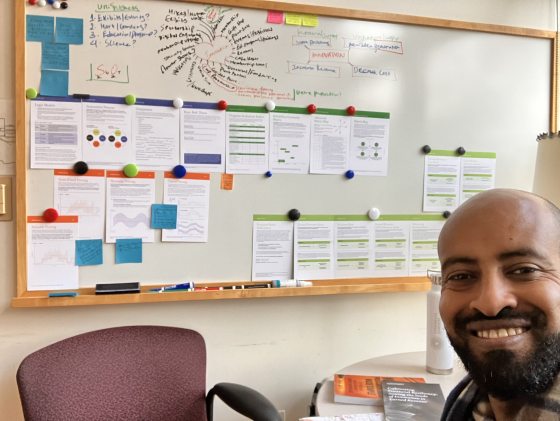

Thanks to the support of HF&G’s leadership team, I was able to jump in fully and quickly. I participated in stakeholder discussions, documented collective insights, contributed ideas reflective of my own professional experience, collaborated with staff and other stakeholders to identify innovative revenue generation ideas, researched potential revenue streams, and assisted in the development of strategic plans. Throughout all of these activities, I worked closely with the leadership team to define the unique value proposition of both campuses.

My time at HF&G was a transformative experience, with rich learning opportunities and interactions characterizing every week. By engaging in various leadership and management meetings, discussions, and activities, I gained invaluable insights into leadership, organizational dynamics, and the importance of consistent communication and organizational collaboration.

Throughout my placement, I had the privilege of witnessing leadership in action, both in formal meetings and informal interactions. I observed leadership styles characterized by humility, simplicity, and inclusivity, and I saw firsthand the value of a humble approach in fostering collaboration and engagement. Additionally, I learned that effective leadership goes above mere task delegation; it entails constant communication, inspiration, and the empowerment of staff to recognize the significance of their contributions to the organization's objectives.

Garden arches at Cleveland Botanical Garden. Photo by Muluken Nega Kebede.

Participating in various meetings, I gleaned insights into the nuances of effective communication and collaboration. Open and focused meetings catalyzed productive outcomes and enhanced team cohesion. I observed how simple activities like icebreakers can foster a sense of unity and enjoyment within the workplace, contributing to a positive organizational culture.

While at HF&G, I also had the unique learning opportunity of witnessing a unionization effort by some staff members. Although challenging for the organization, I learned a profound lesson from the leadership in navigating organizational dynamics related to potentially sensitive subjects. The leadership team’s response exemplified strategic thinking, inclusion, and the ability to articulate the potential impact of various decisions on organizational culture and work environments. Moreover, I learned the importance of addressing overlooked issues from the past, as unresolved tensions can undermine organizational trust and success over the long term. The employees ultimately voted not to unionize, and the issues identified by staff during the process are now being addressed.

As part of my objective to contribute to HF&G’s strategic planning processes and revenue generation efforts, I successfully organized and led four focus group discussions on both campuses (with the help of amazing staff members). The purpose of the focus groups was to gather insights and perspectives from employees in key departments involved in generating revenue and to ensure that ideas for revenue generation align with HF&G’s goals, mission, values, philosophy, and long-term objectives. I facilitated discussions with groups of six to eight participants from specific departments to gather a diverse range of perspectives and ideas. Fortunately, this work built on the previous Fellows’ Cohort Project, which helped me combine focus group findings with valuable insights and tools to identify innovative revenue generation ideas, evaluation tools, and even business opportunities that enhance the guest experience.

Longwood Fellow Muluken Nega Kebede. Photo by Muluken Nega Kebede.

Throughout my field placement, I had the pleasure of exploring the beautiful gardens and plants at both Cleveland Botanical Garden and Holden Arboretum daily. During my free time, I enjoyed walking around the University Circle in Cleveland, an area known for its cultural, educational, religious, and social service institutions. Highlights included learning the history of the city and visiting gardens, the zoo, and museums. I also met anthropologists on a private tour of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, which houses the original cast of Lucy’s skeleton, “the oldest human ancestor,” discovered at the Hadar site in Ethiopia.

One of the special benefits of my field placement was the presence of other Longwood alumni: both CEO Ed Moydell and Vice President of Horticulture Caroline Tait are former Fellows. Their guidance was instrumental in helping me craft my learning objectives and navigate the organization. It was truly inspiring to see successful alumni leaders make a meaningful impact in public horticulture.

From left: Longwood Fellow Muluken Nega Kebede, HF&G CEO Ed Moydell, and HF&G Vice President of Horticulture Caroline Tait. Photo provided by Muluken Nega Kebede.

I had the privilege of being at HF&G just a few months after Moydell was appointed CEO, and I witnessed firsthand how his arrival brought a renewed sense of hope and direction to the organization. His ability to inspire and mobilize the leadership team showcased the transformative power of visionary leadership.

Indeed, my time at HF&G was a journey of profound learning and self-discovery. Through immersive experiences, interactions with diverse teams and stakeholders, and reflective observations, I gained insights that transcend a more traditional educational experience. I left with a deep appreciation for the complexities of organizational dynamics, the importance of effective leadership, and the transformative potential of collaboration and communication. Moving forward, I am inspired to apply these learnings in my future leadership roles, striving to embody the principles of humility, empathy, collaboration, and visionary leadership.

Abby Lorenz

The Alnwick Garden (Alnwick, England)

For field placement, I traveled to a land of ancient castles, rolling hills dotted with sheep, a Poison Garden, a magical village with the world's largest play structure, and plenty of rain. What drew me to The Alnwick Garden, nestled in the heart of Northumberland in the northeast corner of England, was not only the captivating landscape but an organization that defines two of its core values as quirky and caring.

In 1996, the Duchess of Northumberland envisioned The Alnwick Garden as both a beautiful space and a community project. Their focus on social impact dates back to the organization’s inception and was a key priority for me to explore during my two-month placement. I also wanted to understand the key motivations for visitors. My interests aligned with the senior leadership’s goals to increase visitor numbers year-round and evaluate whether their communications about community programs and social impact resonate with their audience.

Families enjoy a day out at The Alnwick Garden on a February morning. Photo by Abby Lorenz.

During my first month at Alnwick, I embedded myself in the Operations team, focusing on assessing programs designed to increase admissions during the week-long school holiday known as “February Half Term.” I explored marketing, ticket pricing, historical admissions data, trends, and past programming to establish a baseline understanding of the factors affecting annual visitor numbers. I collaborated with the Marketing team to modify their existing customer feedback survey, adding questions to gauge which aspects of the value-added programming left a lasting impression. During the event, I collected visitor feedback, observed the level of interaction at each themed activity, and developed an Activity Evaluation Rubric to analyze successes and identify areas for improvement. This analysis, along with a review of customer and employee feedback survey data, was compiled into a comprehensive report on the event.

In early March, I shifted my focus to the Community and Education team. I met with program managers to review their program structures and understand how they had evolved over the years. Some of my most memorable moments at The Alnwick Garden came from participating in and observing these programs. I weeded garden plots with families, handed out pencils to schoolchildren to label their vegetables, and helped an elderly couple living with dementia choose titles for their recorded oral histories. These moments and so many more allowed me to define, for myself, how and why I am a leader in public gardens. As much as I love plants, my drive to continue developing my leadership in this field is fueled by the potential to create spaces where people thrive as well as the landscape around them.

Longwood Fellow Abby Lorenz (left) and The Alnwick Garden Programme Manager Craig Ellis (right), ready to check on the bee colony at the garden. Photo provided by Abby Lorenz.

Throughout my engagements with various teams, I provided feedback and suggestions, seeing the immediate impact of my contributions. The Longwood Fellows Program has equipped me with a deep reservoir of connections, ideas, and resources. I know that opportunities for contribution don’t always come through formal meetings; sometimes, they emerge through informal conversations and asking questions. For instance, I was able to share the Climate Action Toolkit, a resource I found during a visit to Phipps Conservatory, which helped Alnwick’s Climate Action Team streamline their goal-setting process. This toolkit allowed them to benchmark their current efforts and decide where to focus, rather than starting from scratch.

My experience as a Longwood Fellow revealed my strength in building connections. Field placement highlighted this strength in action, and I witnessed its immediate impact on the organization. I also reflected on what this strength means for me and my personal growth and motivation. The way that I work is rooted in listening and understanding the people, systems, and structures in my ecosystem. Moving across an ocean into a different culture challenged me to relearn all that is intuitively known and understood by everyone around me. While this took time and energy, it was incredibly rewarding to build deep connections with people and a place different from where I have previously lived. By the end of my placement, the organization felt like home, and I had developed strong bonds with my colleagues. I returned with newfound confidence in my leadership, as well as a plethora of ideas and inspiration to carry into the next chapter of my career.

Colin Skelly

The Huntington, San Marino, California

It has always been a professional ambition of mine to visit the Desert Garden at The Huntington Botanical Garden. The size and range of the collection and the immersive quality of the planting looked breathtaking—at least in photographs. The opportunity of a field placement at the Huntington, with ample time to see this garden in person, was therefore a hugely exciting prospect.

The Huntington consists of far more than just the Desert Garden, however. Their spaces include the Palm, Camellia, Japanese, Chinese, Herb, Rose, Shakespeare, and Australian Gardens, as well as the remarkable 17th-century Japanese Shoya House that was recently installed. The latter draws on themes of sustainable relationships of humans with the land, as does the Ranch Garden, which applies the same themes to 21st-century California. Altogether it is a remarkable series of collections that make up one of the great gardens of the world.

The Chinese Garden, a relatively recent addition to The Huntington. Photo by Colin Skelly.

My field placement concentrated on the strategic development of the Ranch Garden, a relatively new addition that was first created as an experimental urban agriculture project but now includes a kitchen garden and orchard. As a historian turned horticulturist with a professional focus on ecology and sustainability, I found this area of the garden to be hugely exciting. When Henry Huntington first acquired the site in the early 20th century, it had been a working ranch. Commercial crops like citrus and experimental crops like the potentially commercial avocado were planted along with horticultural introductions like palms (which later became a feature of the LA urban streetscape. The Ranch Garden connects the Huntington’s agricultural past with today’s challenges, carrying on the tradition of experimenting with new crops and developing new ways of growing suitable for Southern California.

The immersive Desert Garden, a remarkable collection and visitor experience. Photo by Colin Skelly.

The Ranch Garden presents stories of soil health, biodiversity, the use of native species, and waterwise practices, with interpretation relevant to a range of audiences. Conservation is a key feature of the Ranch Garden, with an orchard of heritage avocado cultivars preserving genetic diversity when the modern avocado industry relies on a narrow range of cultivars. Toward the end of my field placement, I researched early experiments in avocado cultivation and was struck by the foresight of the early commercial avocado growers. Looking for a source of vegetable fat that could be an alternative to animal meat for a growing population, these early 20th-century horticulturists were anticipating today’s challenges. Wilson Poponoe, a Southern California botanist, searched Guatemala and Mexico on behalf of the US Department of Agriculture to find marketable cultivars of avocado. Of all the possibilities identified, the market is now served largely by the “Haas” variety, so the Huntington’s heritage orchard is an important living collection of older cultivars.

Growing avocados is a challenge that I will take back to the UK! I will also continue to support the sensitive evolution of gardens, especially in adapting historic landscapes to meet contemporary and future climate and ecological challenges. As well as being a source of inspiration and joy for humans, gardens play a vital role in landscape adaptation, whether conserving plants, experimenting with new plant selections in a changing climate, or supporting community urban agricultural programming. Whether old or new, large or small, these themes are relevant to any garden, anywhere in the world.