Among the many treasures that shine during A Longwood Christmas, few are as captivating—or as challenging—as blue coleus (Coleus thyrsoideus), an African member of the mint family known for its striking sapphire-blue flowers. This rare horticultural gem first came to Longwood nearly 70 years ago, and we use that original plant to propagate a crop each year for A Longwood Christmas. With its lovely blue flowers, it serves as one of the most beloved facets of our seasonal display, yet its journey from cutting to conservatory is anything but simple. What makes this plant so unique, and why do we devote such care to ensuring its presence year after year? The answer lies in its rarity, its beauty, and the intricacies required to coax it into bloom, just in time for A Longwood Christmas.

Native to southern tropical Africa, Coleus thyrsoideus first arrived at Longwood in 1957 from New York Botanical Garden. From the start, this plant stood out for its vivid blue spikes, a color so rare in the plant world that an estimated 10% of flowering species exhibit it. Blue pigments in plants do not actually exist. Instead, the coloration may be due to one or a combination of several factors: varying concentrations of different color pigments, molecules and ions, modifications to pigment-regulating genes, pH shifts, and the complex alterations of cell structures that affect the reflection of light and human perception of color.

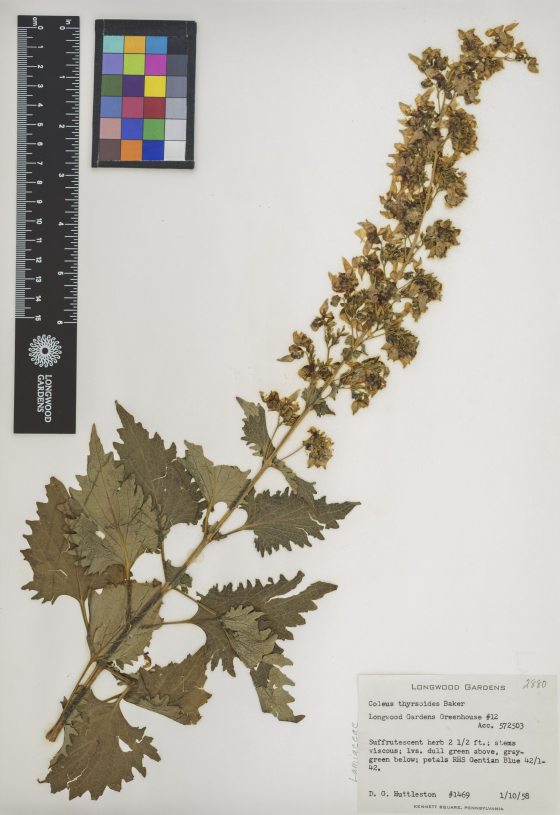

This scan from our database shows the original Coleus thyrsoideus herbarium specimen from 1957.

Coleus thyrsoideus, on display in our Main Conservatory in January 1960. Photo by Gottlieb Hampfler.

This rarity is part of what makes Coleus thyrsoideus so exceptional, its luminous blooms that shine during the shortest days of the year bring a sense of wonder and vibrancy to our holiday display. During this year’s A Longwood Christmas, you can find it in our Main Conservatory, including a front-and-center placement along our Center Walk tree. This sapphire-inspired tree bursts from a blue jewelry box, enveloped by Coleus thyrsoideus and prismatic “crystals” made of Echeveria.

Coleus thyrsoideus, on display in the Main Conservatory in December 2025. Photo by Laurie Carrozzino.

Despite its beauty, Coleus thyrsoideus can be challenging—and takes time. We start working on our holiday crop in mid-June and the process begins with difficult, high-risk propagation. In mid-June we take cuttings from the original plant and place them under humidity domes to encourage rooting, as their cuttings are slow to root, leaving them vulnerable to drying out or disease. Because of this vulnerability, we keep the cutting trays at a constant humidity and soil moisture, and temperatures below 85 degrees Fahrenheit for best success. Over the last several decades, we’ve worked to refine our technique, including making changes to cutting and humidity control. Through those efforts, we’ve improved our propagation success, yet Coleus thyrsoideus remains one of the most difficult crops to start.

Coleus thyrsoideus just beginning its short-day treatment in the greenhouse. Photo by Carol Gross.

Coleus thyrsoideus just beginning its short-day treatment in the greenhouse. Photo by Carol Gross.

After propagation comes growth. This crop requires daily hands-on care. Once rooted, it’s pretty hearty. We shape the plants through pinching to promote branching, potting up during growth, and providing constant structural support; otherwise, its brittle stems would collapse under their own weight. Throughout the summer and fall, the plants receive constant attention—pinching, staking, cleaning yellowing leaves, and monitoring.

This plant naturally wants to grow big and fast, but for display we must control and slow that growth so we can achieve the desired display height. For this year’s A Longwood Christmas, that height was 36 inches. We can tailor the crop’s height by the timing of when we start cuttings or by engaging in different frequencies of pinching. When we are growing it to be smaller than it wants to be, we have to pinch it frequently. Overall, it’s a process that challenges the genetics of the plant, and it’s one that takes a lot of attention.

Floriculture Manager John Leader inspects the A Longwood Christmas crop in the greenhouse. Photo by Carol Gross.

Perhaps the greatest challenge of readying Coleus thyrsoideus for display lies in timing the bloom. Coleus thyrsoideus is a short-day flowering plant, meaning it flowers only when nights are long and days are brief. Light is the key driver of flowering, with 9 to 10 weeks of short days and long nights required to trigger bloom. To achieve bloom, we impose a blackout period of 9 to 10 weeks, with14 hours of darkness daily. Interestingly, this blackout schedule aligns with poinsettias, another holiday favorite. By late November, they are ready for display, where they will remain for about two months, offering guests a rare glimpse of true blue in nature.

Coleus thyrsoideus flanks our Main Conservatory tree during A Longwood Christmas. Photo by Hank Davis.

This process is labor-intensive, but the reward is undeniable. When guests encounter those striking blue spikes amid a sea of holiday color, they experience a living link to Longwood’s horticultural heritage and a testament to the skill and dedication of our horticulturists. Its rarity, its color, and its seasonal timing make it a cornerstone of our holiday tradition, as well as a plant that challenges us, rewards us, and delights all who see it.

A peek of Coleus thyrsoideus between two of our Echeveria crystals. Photo by Laurie Carrozzino.

Throughout the years, researchers at Longwood have experimented with altering its flowering time through day-length adjustments and cultural treatments, but the plant has refused to bloom outside its natural rhythm. This trait, combined with its inability to set seed and its fragile stems, explains why it is rarely grown commercially and why Longwood is one of the few institutions to maintain it.

To ensure the future of this beloved plant, Longwood is planning a plant exploration trip to Malawi in 2026 to collect seeds of Coleus thyrsoideus. By bringing back seeds, we hope to improve the resilience of this iconic display plant. By collecting more seeds, we can grow a genetically diverse population of plants here at Longwood that will allow us to select individuals that might be easier to grow, hybridized with our current plant to improve its health, as well as safeguard it for generations to come. Seeds will also be banked for long-term conservation.

Understanding of plant genetics and evolutionary relationships are always changing as the technology to assess these questions improves and becomes more accessible. Longwood originally obtained this plant under the name Coleus thrysoideus, but this species was subsequently transferred to the closely related genus Plectranthus, and that name was used at the Gardens for a long time. More recent classifications have included it within the genus Coleus, so the decision was recently made to align our nomenclature with this modern concept of the species. Although the change may seem slight (and plant names do change), this helps ensure that our collections data is in alignment with other public garden collection databases and other scientific information related to this species, which all works toward a clearer understanding of this little-known species.

As you enjoy A Longwood Christmas this season, take a moment to appreciate those sapphire blooms; a crop will return for Winter Wonder as well! Behind their serene beauty lies a story of persistence and innovation, and one that continues to unfold.

Editor’s note: At Longwood, art and science meet to create beauty that inspires. On January 24, join us for Science in Action Day as we celebrate our passionate community of experts committed to deepening the world’s understanding of plants. Through engaging presentations, interactions with our scientists, and hands-on activities, gain insight into how Longwood’s applied science is advancing beauty, biodiversity, and sustainability. Learn more about the day’s panel discussion and action stations.