The latest installment of the Nightscape Artist & Friends Speaker Series on September 9 provided a continuation of 2015’s July topic: the importance of music to the Nightscape experience. Justin Geller from Pink Skull rejoined Ricardo Rivera, director of Nightscape and founding member of Klip Collective, and fellow Pink Skull composer Julian Grefe joined the conversation via Skype from Germany. Last year’s panel described the role of Pink Skull in the development of Nightscape, especially their contribution to the Silver Garden and Palm House. Two major changes to this year’s installations extended the collaboration between Pink Skull and Klip Collective and focused on Peirce’s Woods and the Waterlily Display.

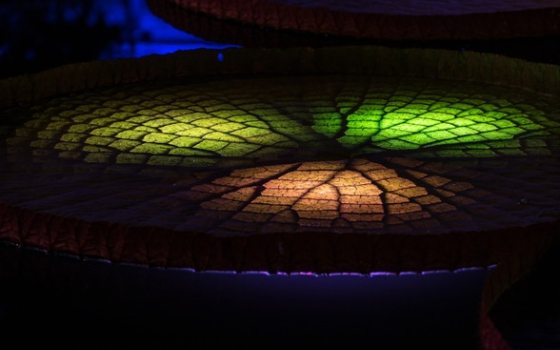

Light, music, and poetry accentuate the natural beauty of this water-platter. Photo by Hank Davis.

Rivera reminded the audience about the integral role the soundtrack plays in the Nightscape experience. More than just a background detail, the music gives both emotional form and substance to the viewer’s experience. One of Rivera’s favorite pieces of guest feedback (and one of the most consistent) is the overwhelmingly positive response to the Large Lake. In fact, several marriage proposals have occurred at this location, and Rivera credits the Large Lake’s music for its emotional pull. When Longwood asked Klip Collective to revive Nightscape for the 2016 season, Rivera knew right away that he would be contacting the soundtrack’s creators for additional music.

While most of Klip Collective’s work involves both light and sound, the installations at Longwood have required their own unique form of collaboration. “Unlike a lot of my other work where I create visuals and someone composes something for it, this is much more of a collaborative process,” said Rivera. “A lot of the composers came here and we spoke about what we wanted to do. We worked hand in hand, back and forth.” Grefe provided an example of this side by side process: this year’s display includes a new experience in the Waterlily Display and required a totally fresh soundtrack. Rivera installed lights in the actual pools rather than rely on projectors and projection mapping, and Grefe took inspiration from Claude Debussey’s well-known classical piece Clair de Lune for the music. Grefe’s composition is a 25-minute loop that builds on cello, harp, and spoken word vocals. Local research provided Grefe with the spoken word component—the words come from Bryn Mawr College poet Marianne Moore. Grefe felt that Moore’s geographic roots “tap into the psyche of the [Philadelphia] area” and that this would only enhance the overall experience of the sound.

The “light of the moon” inspires the Waterlily Display this year at Nightscape. Photo by Hank Davis.

Rivera expressed how moving the Waterlily Display feels at night. “It’s an installation—we make art that is something you can walk through, not something you can share on Instagram,” described Rivera. “You have to be here and feel it, and I think the music really does that. This installation is a multi-tiered experience, meaning there’s a lot of different things working together. In the Waterlily Display we have the music, architecture, the lights lighting up the architecture, and then we have the beautiful plants within it that are also being illuminated. I think this area is a very visceral experience—you feel it. And it’s a special, magical place.”

2016 provided the team with the chance to place this magic in another new spot in the Gardens: Peirce’s Woods, which most guests walk through after pausing at the Large Lake. This location allowed Rivera to work on a project that he had thought about for years. “One of the original visions [for Nightscape] was to do several installations in the woods along a hiking trail,” describes Rivera. “This vision was always walking in dark woods and having the trees illuminated around you … Peirce’s Woods is dark, it’s mysterious, and it’s like the opposite of the Topiary Garden, which has beautiful form and so much purpose.”

The music soars along with the trees in Peirce’s Woods during Nightscape. Photo by Hank Davis.

Rivera described wanting a song of epic magnitude for the woods, and Pink Skull came through with a soundtrack inspired by Bach’s Cello Suite #1 in D Major, another very recognizable classical piece. “I went through and made a recreation of it, taking iterations and expanding on them,” said Grefe. He added additional layers of piano, and a close listener can hear the echo of the “arpeggio taken out of the original cello line as well as the down strokes of the cello.” An additional layer of violin “made it a little more summery and less somber” as well. “When I heard this I thought ‘This doesn’t belong just anywhere—it belongs in Peirce’s Woods,’” said Rivera. “It’s just such a nice, big song.” While one wouldn’t confuse the final soundtrack with Bach, Grefe and Rivera agree that the new music offers the same general feeling to the listener while providing the guest with a transition away from the Large Lake into the rest of the Gardens.

At the event’s conclusion, Rivera tried to summarize why figuring out Nightscape’s layers of sound and visuals has been uniquely satisfying. “Nightscape has been so great because of its breadth,” he described. The entire installation has so many pieces that make up a whole experience, and some spaces are very emotionally accessible, he reasoned. But other spaces are “really weird” and challenging to grasp. This latter component hasn’t bothered Rivera during Nightscape’s two summer seasons, and he actually sent back early versions of music that weren’t “weird enough” for some parts of the installment. Grefe and Geller agreed that creating something that pushed beyond “weird” had its own set of challenges, but the ultimate journey provided by the installment matches the collaborative vision of the team. “I got a lot of comments last year about how dark and moody it was,” recalled Rivera. “But it’s at night and it has that vibe—I didn’t come here to make that ‘Disney World’ experience. It had to be something true to what we wanted to do.” For guests who have the opportunity to view both seasons of Nightscape, they can compare how these updates and expanded Garden features transition from one year to the next.

The soundtrack of Nightscape is available via digital download at Amazon and Bandcamp.