This week brings with it our next Luminaria Nights—special evenings in which guests can see our Gardens in a new light, thanks to thousands of luminaria that not only evoke beauty, but tell a beautiful story. On October 5, 6, and 7, we are thrilled to share a Luminaria Nights display inspired by the artform of sashiko—a traditional hand-stitching practice developed in Japan that has evolved over centuries into a cherished craft. During these special evenings, about 2,000 luminaria will glow in our Main Fountain Garden, placed in a Kasumi Tsunagi pattern of wavy lines from which cloud-like shapes emerge. Not only are these Luminaria Nights a way for guests to experience our Gardens in a new light … they’re also a way in which to showcase the beauty, the story, and the meaning of this expressive, creative artform that we are honored to share.

Longwood’s Associate Director of Landscape Architecture and Programs Erin Feeney—who designs and brings to life our Luminaria Nights displays—has long admired the geometric aesthetic and story of sashiko. This week’s Luminaria Nights serves as the second time in which Feeney has worked closely with sashiko artisan and curator Atsushi Futatsuya on artfully and accurately representing this Japanese craft in luminaria form—the first of which was our October 2021 Luminaria Nights in a Seigaiha geometric wave pattern.

The October 20212 Luminaria Nights geometric wave pattern was inspired by the sashiko pattern of Seigaiha, witih layered concentric circles representing a calm ocean and the hope for life to be of good fortune. Photo by Eileen Tercha.

Born into a surviving sashiko family in Gifu Prefecture, Japan, Futatsuya is dedicated to sharing sashiko with the world. Through his organization UpCycle Stitches, Futatsuya shares the techniques and mindset of the artform by leading workshops, providing supplies and materials, and educating others about sahiko’s layered history. Dating back to the Edo period (1615–1868), a form of sashiko began when working-class farming and fishing families developed the practice to preserve their textiles and clothing by making the fabric thicker, warmer, and stronger—all as a means of survival. Using a running stitch employed by repeating or interlocking traditional Japanese geometric patterns, these families would stitch a worn-out piece with layers of old cloth to produce a sturdy garment to then be passed down through generations.

By the Meiji Era (1868–1912), even personal protective garments such as firefighting coats were created using sashiko, thanks to its strength and durability. In the 1960s, it experienced a revival in some communities. Throughout the centuries, sashiko has evolved from a frugal, functional, and utilitarian necessity for survival into a highly regarded artform focused on expression and creativity.

Sashiko’s patterns and stories hold beauty all their own. Dating back to sashiko’s origin, the patterns that sewists developed and used were meant to protect the wearer or tell stories of family, self, or culture. Many of these patterns are hand-drawn, utilize sashiko’s distinctive element of using blank space as an integral part of the overall pattern, and often represent things found in nature—and this week’s luminaria display, inspired by the sashiko pattern of Kasumi Tsunagi, is no exception.

With Kasumi meaning haze, mist, or fog and Tsunagi meaning to connect, the pattern is inspired by water’s transitioning states and the many ways water contributes to and is celebrated in the Main Fountain Garden. To Feeney, the concept reminded her of the states of transition for gardens, as gardens themselves constantly evolve—as we all do as living beings. The concept also serves as a companion to our October 2021 luminaria sashiko pattern of Seigaiha (Blue Sea Waves), in which both focus on water. Kasumi patterns are often used in Japanese design and can be even seen on ancient picture scrolls, used to express the passage of time. As the Kasumi pattern repeats, its form vanishes and then appears again, translating into the meaning of eternity. With Tsunagi meaning to connect, the pattern becomes continuous and speaks to changing seasons, as Futatsuya explains.

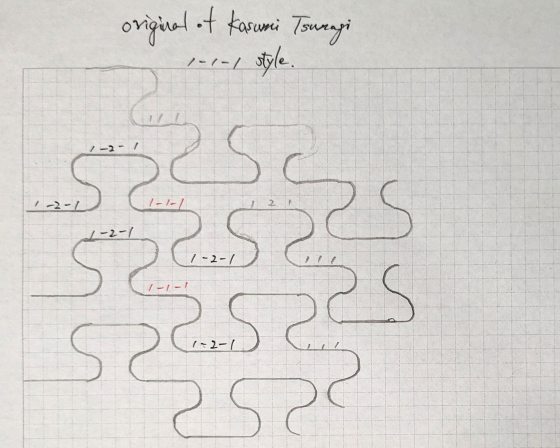

Futatsuya’s hand-drawn Kasumi Tsunagi pattern, as shown on grid paper. Each grid measures 5 millimeters, and Futatsuya often calls this approach “1-1-1 style”. Drawing provided by Atsushi Futatsuya.

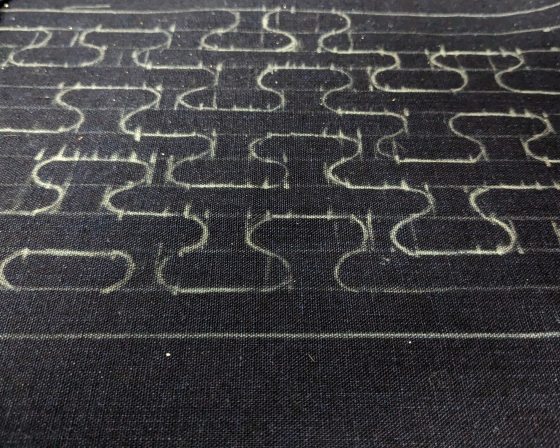

Using the hand-drawn pattern, Futatsuya then drew the Kasumi Tsunagi pattern on fabric before hand-stitching it. The pattern is viewed here from an oblique angle. Drawing provided by Atsushi Futatsuya.

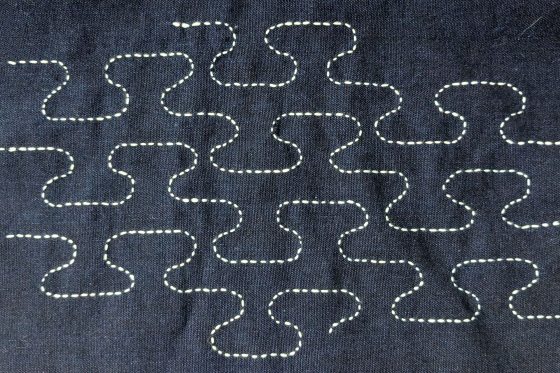

Futatsuya hand-stitched this sample of the Kasumi Tsunagi pattern on fabric using the small grid approach, noting its difficulty to make even stitches as the pattern’s curves are quite tight. Photo by Atsushi Futatsuya.

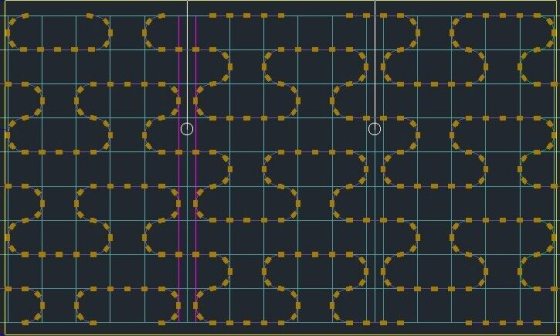

Feeney uses computer-aided design (CAD) when planning each luminaria display. This CAD snapshot shows the rhythm of the Kasumi Tsunagi pattern, imagined for the Main Fountain Garden. Photo provided by Erin Feeney.

Working together, Feeney and Futatsuya used the Kasumi Tsunagi pattern as the main focus of the luminaria design, playing with linework and spacing to create a pattern that would not only fit within the spacing of the Main Fountain Gardens’ trees and allées, but also complement the entire garden’s architectural features. This work to adapt the pattern to the space reflects the variations seen in the artform of sashiko itself—sashiko artisans start with and respect established sashiko patterns, but then work to make something that is their own, reflective of who they are and the story they’d like to tell.

You’ll also find luminaria along walkways in the Conservatory amid our Chrysanthemum Festival display this weekend. Photo by Becca Mathias.

As in sashiko, Feeney designed the display to be viewed from a primary view—the elevated perspective of the Fountain Terrace near the Rectangular Basin, on the south side of the Main Fountain Garden. From there, guests can see intricacy of the Kasumi Tsunagi pattern. While the Luminaria Nights display itself will be stunning, it’s the process in which it was conceptualized, designed, and realized—thanks to Futatsuya’s expert collaboration, and our team of staff and volunteers who carefully place and light each and every luminary—is what makes it truly beautiful.

Join us for our October 5, 6, and 7 Luminaria Nights to see the Kasumi Tsunagi pattern and experience the beauty of sashiko in person. While you’re here, stroll along the additional 1,000 luminaria illuminating the walkways of our Conservatory. There, you’ll experience amid Chrysanthemum Festival, where the complexity and exquisite forms of the chrysanthemum meet the horticultural artistry of our specialty forms in the soaring spaces of our Conservatory.