Our 2024 Community Read book, The Last Garden in England by Julia Kelly, isn’t just a remarkable selection that exemplifies the meaning we can all find in gardens—it also has a fascinating historic agricultural connection to Longwood Gardens. This historical fiction piece takes place at Highbury House—whose lovely gardens are at the center of the novel—in 1907, 1944, and present day, connecting five women—from the gardens’ original designer to the modern-day designer charged with restoring their beauty—all of whom find true meaning and solace in the gardens. One of those women is the character of Beth Pedley, a “land girl” (a nickname for workers in the Women’s Land Army, or WLA) assigned to be an agricultural laborer at one of Highbury’s neighboring farms to help keep food on British tables during World War II. Women organizing to support wartime agriculture is part of the real-life history of Longwood Gardens—a story (and connection to our Community Read selection) we’re delighted to share here.

During America’s involvement in World War I, the Women’s Land Army of America (WLAA), which was inspired by the British WLA, saw women joining forces to take the place of male agricultural workers who had been sent off to war. At least six “farmerettes”—the American equivalent of land girls—lived and worked on Longwood property.

Women's Land Army of America recruitment poster, 1918. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [LC-DIG-ppmsca-13492]

The British WLA was first started in 1917 during World War I to provide workers to continue food production and was restarted in 1939 during World War II. According to the Imperial War Museums (UK) more than 80,000 land girls were working in the WLA at its peak in 1944, when The Last Garden in England’s Beth arrived at the farm as a land girl: “Her life was about to become all soil and crops and weather and harvest. She’d heard during her training that the isolation of rural life could be difficult for city girls like her, but she’d spent her childhood on a farm. She was sure it would be like returning home” (p. 27).

In the United States during World War I, the WLAA initially organized through regional women’s groups and schools, including in the Philadelphia area. The Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women in Ambler, PA (now Temple University Ambler) joined other women’s agricultural groups to provide coursework and training to farmerettes who would be disbursed to regional farms to help with the war effort.

Women’s Land Army, Pennsylvania School of Horticulture. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries. Philadelphia, PA.

Training centers also popped up on the estates of wealthy women, like Mary K. “May” Gibson of Wynnewood. Her garden-filled estate, “Maybrook,” had been built for the family by her father, distillery heir and arts patron Henry Clay Gibson, along the Main Line outside Philadelphia. Chairman of the board of directors of the Land Army of Pennsylvania, Gibson employed her family’s home in a lifelong habit of hospitality and service. After establishing one of the first WLAA units, she quickly expanded her efforts into a six-week training course, where Cornell College graduates taught about 60 girls at a time to care for livestock and fields.

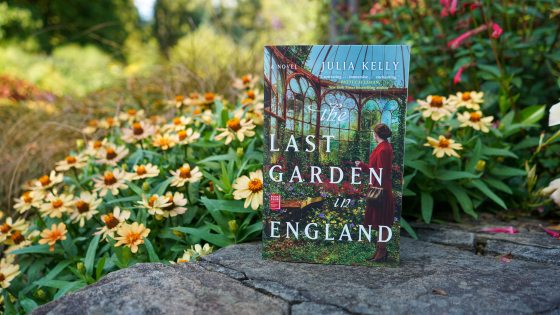

The Last Garden in England by Julia Kelly. Photo by Carol Gross.

These Maybrook trainees included a group of six girls that ended up at Longwood Farms, where they lived in one of the estate’s houses near the corner of present-day Longwood and Conservatory Roads. Known as the Workmen’s House, the building was constructed in 1917 to house laborers on the estate before hosting the farmerettes. The 8-bedroom house is pictured at the top of this post (image courtesy Hagley Museum and Library).

Longwood farmerette Mary Geiger Peirce of Philadelphia. From Philadelphia Inquirer, July 24, 1921.

One of this group was Mary Geiger Peirce of Philadelphia. She would later describe her time to a Philadelphia Inquirer reporter: “…six girl farmerettes, including myself, lived in an old farmhouse – roughing it and having the time of our lives. The work was terribly hard, and sometimes when I went to bed I was so stiff I could scarcely move.” According to the WLAA structure, the group of women would have lived together in a unit, taking care of their own housekeeping apart from farm families. Designed to provide safety and comfort for the farmerettes, it also helped avoid adding the burden of boarders to already-busy farmers’ wives.

The farmerettes stationed at Longwood may have worked in the new milk-producing creamery on the former Merrick Farm, as shown in this 1920s photo.

There would certainly have been plenty to do on Longwood Farms, as many male employees had left for service with the armed forces. During the war years, Longwood Farms had a thriving vegetable garden, which would have supplied not only the “mansion house” but also the many employees’ families who lived on the property. There were also fields of alfalfa, potatoes, wheat, and corn, as well as livestock operations that featured Guernsey cows, Hereford steers, and registered Berkshire hogs, along with chickens and turkeys. The Guernsey herd was growing and producing rich, high-fat milk to be processed in a new creamery on the former Merrick farm, a parcel of land along Street Road that Longwood founder Pierre du Pont purchased in 1915. The training the farmerettes received at Maybrook would have been very useful indeed!

Editor’s note: We invite you to join author Julia Kelly for our Looking Back to Create Something New Community Read Conversation on March 26 as she discusses the inspirations behind The Last Garden in England. Explore the real-life people and gardens that inspired her to write this historical fiction novel; attendees will have an opportunity to ask questions. Also, check out our Community Read Calendar for more on regional partner programs related to The Last Garden in England, or our children’s Community Read book The Secret Garden.