The return of our Chrysanthemum Festival puts our most horticulturally rigorous display on center stage—it’s a celebration of rare varieties, artfully trained forms, and the extraordinary care behind each bloom. It’s also a tribute to an ancient Asian artform rooted in China and Japan, honoring a rich tradition of plant science and cultural tradition that spans continents and centuries. Our world-class chrysanthemum collection features primarily cultivars and hybrids developed in Japan and China … and a rare Japanese book recently acquired by the Longwood Library reflects the beauty and the long-standing importance of the chrysanthemum to Japanese culture. This newly acquired work is also astounding in its level of intricate detail, perfectly capturing the complexity of cultivars on display in our Main and East Conservatories right now.

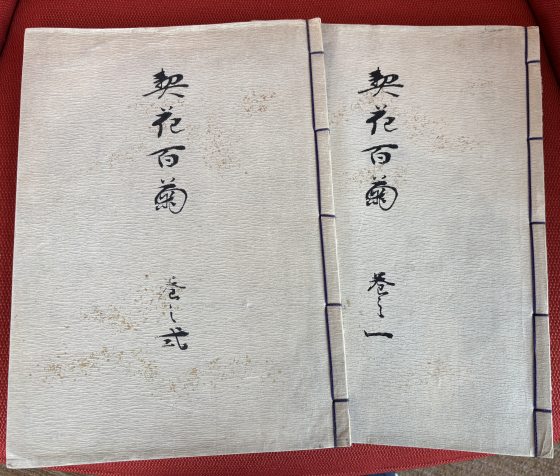

Published in 1893, the three-volume One Hundred Chrysanthemums by artist Keika Hasegawa—of which the Longwood Library now owns the first two volumes—contains stunningly beautiful color woodblock illustrations of single-stem chrysanthemums. These first two volumes contain 50 illustrations that showcase the wide variety of forms, colors, and characteristics of this beautiful autumnal flower.

A rich, velvety bloom with deep crimson petals that gently curve inward, Chrysanthemum × morifolium ‘Crimson Tide’ features beautiful bronze undertones—beautifully depicted in one of the woodcutting prints from One Hundred Chrysanthemums. You can see this beauty on display in the East Conservatory in our chrysanthemum class display. Photo on left by Cathy Matos; image on right from One Hundred Chrysanthemums by Keika Hasegawa (1893). From Longwood Gardens Library rare book collection.

Chrysanthemums likely originated in China; references to mums are found in Chinese records as early as 500 BC. It is thought that Chinese monks likely carried chrysanthemums to Japan around the 8th century AD. The monks also brought to Japan the traditions of the Chinese festival of the chrysanthemum known there as the Double Ninth Festival, occurring on the ninth day of the ninth month. The publication of One Hundred Chrysanthemums occurred in the middle of Japan’s Meiji period (Emperor Meiji reigned from 1868-1912). A 16-petal chrysanthemum was adopted as his Japanese imperial crest in 1868, and in 1910 it became the national flower of Japan. The emperor hosted an exclusive garden party in 1878 to view mums grown in one of his gardens.

Botanical illustrations can sometimes capture what words cannot. Historically, illustrations were the most effective way to document plant diversity and to capture details of structure, form, or color with precision. They also created countless opportunities to share the wonders of the natural world. Even today, botanical illustrations can feature diagnostic features that a camera might miss. As a botanical and horticultural library, it is important that the Longwood Library continues to collect and preserve such literature.

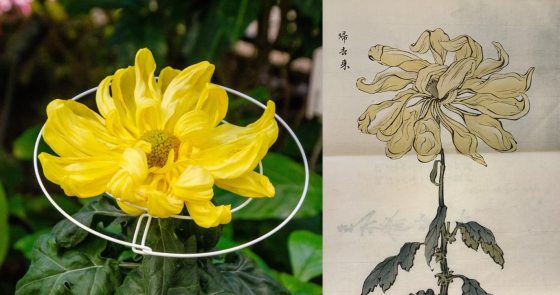

A refined chrysanthemum with delicately curling petals that unfurl like silken ribbons, Chrysanthemum × morifolium ‘Kishi-no-tenshukaku’ is elegant and subtly dramatic. You can see these flowers in the East Conservatory throughout Chrysanthemum Festival. The woodblock print looks very similar, especially the gossamer nature of the petals. Photo on left by Amy Simon Berg; image on right from One Hundred Chrysanthemums by Keika Hasegawa (1893). From Longwood Gardens Library rare book collection.

Woodblock printing has been around for centuries in Japan, and involves not just the artist, but the engraver, printer, and publisher. The design was first done on paper, which was pasted to a block of wood, then chiseled and cut to create a negative of the original. Colored ink was applied to the block, paper was laid over it, and rubbing a pad over it made a print. A separate block was used for each color in the print. This technique is evident in One Hundred Chrysanthemums, with some illustrations even featuring additional hand-coloring.

With petals like brushed silk, ‘Kishi-no-Paris’ carries a quiet elegance. Soft shades of ivory catch the light, surrounding a bright center, giving each bloom a luminous quality. This flower can be found in the East Conservatory, not far from the ‘Kishi-no-tenshukaku.’ The woodblock print captures the delicate nature of the petals.

The cover of One Hundred Chrysanthemums by artist Keika Hasegawa, of which two volumes are now part of the Longwood Library’s rare book collection. The Smithsonian Library and Archives also owns two volumes, which have been scanned and are viewable through the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Photo by Gillian Hayward.

Beyond their artistic value, these woodprints bridge the observational world between art and technical study. Longwood Grower and Propagator Patti Stefanick, who curates our chrysanthemum collection, recognized how similar individual cultivars in our living collection appear to those in the woodblock prints. These exceptional similarities illustrate how our chrysanthemum collection captures genetics that match the look of plants from long ago—and our dedication to preserving germplasm for the future. With the recent acquisition of One Hundred Chrysanthemums, we are preserving this important piece of art.

Today, Longwood’s chrysanthemum collection encompasses 197 cultivars, anchored by a core collection of 47 Japanese-origin and Japanese-style varieties. This core collection is nationally accredited through the American Public Gardens Association, recognizing it as one of the most carefully curated and significant assemblages of chrysanthemums in the country. Outside of Japan, some of our cultivars only exist here. Each plant is meticulously tended by our team, who carry forward centuries of horticultural artistry and tradition.

Bold and sculptural, Chrysanthemum × morifolium ‘Lili Gallon’ turns heads with its striking contrast of deep magenta and pale pink petals. Each curl and twist is intricately woven, with vibrant inner petals spill outward in a lively rhythm, creating a sense of movement and depth. You can find this bloom in the East Conservatory. Photo on left by Jessica Turner-Skoff; image on right from One Hundred Chrysanthemums by Keika Hasegawa (1893). From Longwood Gardens Library rare book collection.

Just as the woodblock printing used in One Hundred Chrysanthemums requires the hands of many, so does the artistry and science required for our Chrysanthemum Festival. As our most horticulturally intense display, this complex endeavor is supported by many at Longwood—the end result one in which many have worked together to create a living masterpiece. Here at Longwood, where living and nonliving collections meet—where plants coexist with art, books, and objects—we share a deeper, timeless story about cultural heritage and how humans think about, relate to, shape, and celebrate nature.

On view now through November 16, Chrysanthemum Festival serves as our love letter to this charismatic flower that has been celebrated, cultivated, and cherished for thousands of years. New this year, we give a behind-the-scenes look at the art and science behind Chrysanthemum Festival with an exhibit about the display. While you’re here, be sure to visit the exhibit and learn more about chrysanthemum cultivation, to stewarding our collection, to the many hands who bring the display to life.