“There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot.” —Aldo Leopold

Aldo Leopold—conservationist, naturalist, philosopher—was one who could not. His career in forestry and wildlife management and his keen observations of the natural world inspired him to write A Sand County Almanac, so he could share his thoughts about nature, humanity, and the connections between them.

From now through mid-April, Longwood Gardens invites you to take part in our first annual Community Read, which features Leopold's conservation classic. Read the book, think about the issues of land, legacy, and community that it raises, and engage in activities and discussions at Longwood, at one of our partnering institutions, or join in our discussion on social media.

In A Sand County Almanac, Leopold bids us to come and listen to stories of the land—stories we once knew, but may have recently forgotten. In "Good Oak," each ring is a record of the old tree’s growth, each cut of the saw a slice through time—a reminder of the slow processes involved in the creation of our natural resources. Leopold’s voice is poetic yet precise, conveying the wonders of both beauty and science. It is a voice that slows our hectic pace so we can begin to know the wisdom of nature itself.

In "Thinking Like A Mountain," Leopold describes how his own relationship with nature changed over time. At first he was the youthful conqueror who believed that eliminating predators would leave behind larger deer herds for hunters. But it was the memory of “a fierce green fire dying” in the eyes of a wolf he had slain that later awakened Leopold's voice as citizen of the land—a voice that called for balancing the privilege of partaking of the land's bounty with a responsibility for its stewardship.

The Longwood Connection

The story of Longwood Gardens also speaks of land, legacy, and community, in a voice that balances privilege with responsibility, beauty with knowledge. Pierre S. du Pont and Aldo Leopold shared an era that witnessed the rise of national forests and public parks, and each man played his part. In 1906, du Pont purchased Peirce's Park, the land destined to become Longwood, to save its trees from destruction. Leopold began forestry studies at Yale in that same year, joined the newly formed U.S. Forest Service in 1909, then embarked on a career in wildlife management.

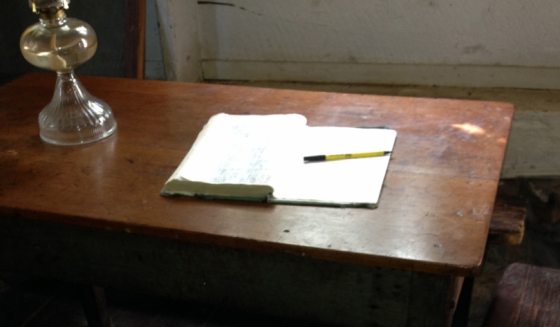

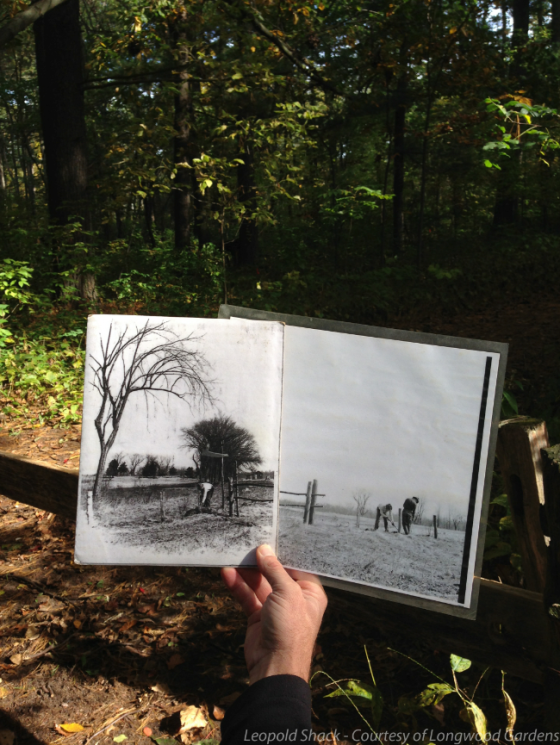

In 1917, du Pont purchased adjoining farms that would later become Longwood's Meadow Garden, while in 1935 Leopold acquired "the shack" and the worn-out, abandoned sand farm along the Wisconsin River that would become his family's "week-end refuge” and experiment in ecological restoration. It would also become a source of inspiration for A Sand County Almanac.

Today the legacy of Aldo Leopold lives on in his essays and in the work of The Aldo Leopold Foundation, while the legacy of Pierre S. du Pont lives on in Longwood Gardens. Each is committed to natural beauty, education, and stewardship.

Going Forward

After reading A Sand County Almanac, one might argue that none of us can live without wild things, that we are wholly linked through the community of the land. To live without wild things is to put at risk the air we breathe, the food we eat, the beauty that nourishes us, and the communities that sustain us.

Leopold put forth these ideas in his closing essay, "The Land Ethic," in which he writes, "Nothing so important as an ethic is ever 'written' . . . it evolve[s] in the minds of a thinking community." Leopold's biographer, Curt Meine, who will be featured in a future blog post and who will visit Longwood on April 12, reminds us that Leopold "did not, and could not, 'write' the land ethic. No one person could. And everyone could."

These words go to the heart of what Longwood's Community Read is all about. They echo from the rings of a good oak, from the green fire fading in a dying wolf's eyes, from the wisdom of a mountain. And yet these voices from the past can lead us forward. Today they resonate in the vibrant stillness of a meadow and in the minds of a thinking community who come together to read, think about, and engage in A Sand County Almanac. These are the voices that will discover new and better ways to carry our community of the land into a sustainable future.