Editor's Note: Join us at the Mütter Museum on April 4, 2019, for The Strange World of Seeds: Book Talk and Signing to hear more about how these tiny marvels have shaped human history.

This year at Longwood Gardens, it’s all about seeds. Few people have explored these marvels of form and function as closely—and as broadly—as Thor Hanson, award-winning author of our 2019 Community Read selection, The Triumph of Seeds: How Grains, Nuts, Kernels, Pulses, & Pips Conquered the Plant Kingdom and Shaped Human History.

Hanson tells the tale of how seeds have shaped finch beaks, rodent jaws, and human skulls, not to mention human cultures and economies. He helps us imagine the myriad ways in which seeds travel, endure, defend themselves, and nourish the life within, in what he calls “an elegant and endless articulation of the possible.” We even learn that our fondness for caffeine, a weakness we share with honeybees, may be due to the evolutionary cunning of seeds.

As skillful a storyteller as he is a scientist, Hanson weaves each chapter into the next, inviting us to read on—mirroring the process of science, in which one question leads to another. Recently we had a few questions of our own for the author about his research, his writing … and what comes next.

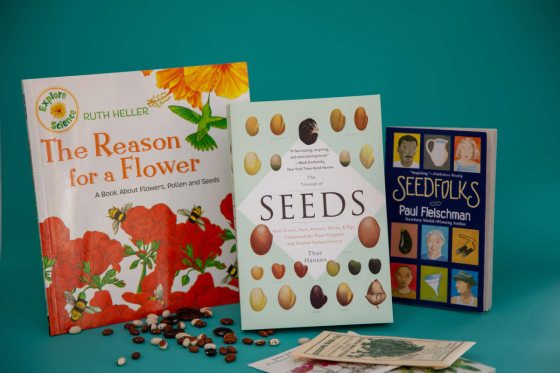

Our 2019 Community Read selections for young readers, adults, and middle grade readers. Photo by Carol DeGuiseppi.

Here’s what Thor had to say:

The Triumph of Seeds was a wonderful journey of discovery for me. After years of sampling and mapping almendro* seeds and trees in Central America, I realized I hardly knew anything about how seeds worked. Writing this book became a chance to dive deeper—an excursion into all things seeds.

Why is the book called The Triumph of Seeds?

I knew this was a story of triumph. If you consider how seeds evolved from spores to become dominant and diverse throughout the ecosystems of earth, you have to ask what were the key traits of seeds that allowed that transition in nature? But it also became an exploration of the human relationship with seeds, and how they triumphed over us, since we’re so dependent on them for food and medicine and all sorts of products.

What about seeds most astonishes you? What question, for you, is left unanswered?

What I find astonishing is the diversity of traits that allows seeds to be so successful. If I were at the beginning of my career, I would study dormancy—the ability of seeds to pause in their development and yet still be alive, while evolving strategies for coming out of dormancy at just the right moment—that process remains so mysterious. The research into dormancy—where a seed undergoes something like 90% desiccation for months or years, but retains a memory of both its structure and function—has applications far outside botany. The world’s first dry vaccines were recently developed using a sugary “bio-glass” extracted from legume seeds and rice grains.

Much of the pleasure of reading The Triumph of Seeds comes from meandering across space and time and topic—from the Central American rainforest to a Seattle coffee shop, from the American Civil War to the Arab Spring, from the spicy heat of chilies to the design of the Stealth bomber. How did you go about researching this book?

The process for me has the sense of a journey, learning as I go, from the science to its deep cultural connections. It’s usually a two- to three-year process. But looking back, I can see at what point the narrative starts to flow and the book takes on a life of its own. There becomes a logic to what comes next. For The Triumph of Seeds, the key sections like dormancy, dispersal, and defense created the flow.

What about the future of seeds and hope for the future?

Seeds are inherently a metaphor for survival, longevity, and rebirth. There are seeds lurking in the soil under parking lots in developed areas, waiting and willing to sprout when the asphalt starts to crumble. They’re about adaptability and toughness and taking advantage of opportunities in the rapidly evolving landscape all around us. There’s great resiliency in nature. Knowing their story helps us refocus our energy on what’s at risk in our modern world, which is basically our way of life.

“Seeds embody the biology of passing things down. In a sense, that is also the root of their deep cultural significance. Seeds give us a tangible connection from past to future, a reminder of human relationships as well as the natural rhythms of season and soil.” From The Triumph of Seeds. Photo by Carol DeGuiseppi.

And then there are orchids …

Orchids are at the cusp of seed evolution. One of every 10 species of plants in the world today is an orchid, so it makes you think they’re on to something. Their seeds are like dust, with no sophisticated strategies for dispersal, defense, or food storage. What orchids do have is a mutualism with fungi in the soil. It’s an intriguing evolutionary pathway, like the spores that seeds evolved from.

After reading The Triumph of Seeds, readers will want to come back for more, like honeybees to coffee flowers. Tell us about your newest book, Buzz … and what comes next?

Above all other insects, bees are the closest to us. And because of their key role as pollinators, it wasn’t a big step from seeds to bees. I can trace my interest in bees back to my study of seed dispersal in the almendro of Central America. That tree is in the pea family, so I knew that way up in its branches, its pollinators had to be bees. Next I’m writing a book about the natural history of climate change: how plants and animals respond to rapid changes in their environment in real-time evolution.

You’ve grown Mendel’s peas in your garden in the past. What are you growing now?

We have a wonderful, big garden with berries and a fruit orchard, where I consider myself mostly a “garden enabler” for my wife. But there’s a little bed in front of my office where I’m planting native plants for the bees: red-flowering currant, gooseberry, and a fabulous little Douglas aster, which attracts bees, butterflies, and hoverflies.

What is in store for guests who come to hear you speak?

Well, there will be lots of seed stories, some from the book and some from more recent projects. And lots of pictures, which are hard to squeeze into a book. I particularly love the Q&A period, which gives me a chance to interact with people who are interested in the topic, and can lead to spontaneous and fun stories.

Why tell science as a story?

The bulk of my training has been in conservation biology, where I’ve often seen fascinating projects that never make it beyond the relatively limited audience of peer review. That process is an important part of science, but it’s also important to take those stories further, and translate them to a broader audience. Some people might think they don’t like science, but what they don’t like is the jargon. What people love is the excitement of discovery. My favorite comment, from someone who has read the book because their book club picked it, goes something like this: “Hey, I read your book—and I can’t believe I liked it!”

Thor Hanson “bee-tubing” among the flowers, collecting bees to marvel at and identify, before releasing them back to the garden. Photo by the author’s son, Noah Hanson.

Whether or not you like science—or history, or gardening, or coffee—maybe the best reason to pick up The Triumph of Seeds is for the wonder it inspires. In one passage, Hanson describes watching the soaring flight of a large, hard-to-come-by, winged Javan cucumber seed with his young son, Noah. “We watched that seed fly for the simple joy of seeing something beautiful doing what it is meant to do,” he writes. On the phone, however, his sense of wonder takes a more head-scratching tone: “We still wonder where that seed went,” he says with a laugh.

To hear more seed stories from author Thor Hanson, please join us at the Mütter Museum on April 4, 2019, for The Strange World of Seeds: Book Talk and Signing; and at Longwood Gardens on April 5, 2019, for A Community Conversation with Thor Hanson.

*Dipteryx oleifera, known commonly in its native range as almendro, is a large tree in the bean family and is an important source of food in tropical Central American forests.