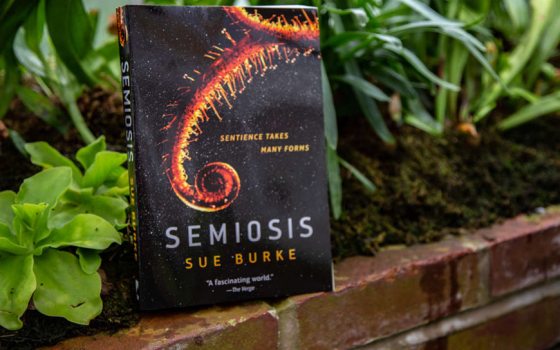

Now in its seventh year, a rousing conversation has always been a defining feature of our Community Read. But this year marks a few firsts, including our first science fiction selection—Semiosis, by debut novelist Sue Burke, whose tale of first contact between human colonists and intelligent plant life on the planet Pax invites plants (for the first time!) to join the conversation. The title, Semiosis, suggests a means of communication that transcends human language, and thus expresses the quest of all good science fiction—to discover realms of imagination and possibility yet unknown.

In our 2020 Community Read and beyond, Longwood’s Library and Information Services Director David Sleasman hopes to explore plant life from different perspectives (and voices). “Sue’s novel gives narrative life to emerging ideas about the essence of plants,” he says, “even as scientific research is advancing the way we understand species so different from our own.” Here Burke shares her authorly insights into science fiction, plant sentience, and the writing process …

You’ve said that the idea for this book started with the houseplants on your dining room table. Can you tell us a little about that, and your research for Semiosis?

My mother loved gardening and houseplants, and she instilled that love in me. In the 1990s, one of my houseplants, a pothos, wrapped around another plant, starved it for light, and killed it. At first I blamed that on my own neglect, but a month later another plant went on the attack. I got suspicious. I began to do research into plants and discovered they can be murderously aggressive as well as generously cooperative.

That idea stuck with me, and eventually I wrote a short story about murderous plants. Later, when I decided to use that short story as Chapter One of a novel, I realized I needed to do a lot more research to create the novel’s world: how planets form, how life developed on Earth, and how plants function. At the time, I was living in Spain, so my daily life was one continuous research project into culture and language.

Why did you tell the story over the course of seven generations? How did you decide who would tell each generation’s story?

We are high-speed, high-energy beings. Plants create their own energy, but less of it, so they do things more slowly. Stevland [a bamboo] would need time to find out that humans had arrived on his planet and then figure out what to do about them. One way to give him time would be to write one chapter per generation until he caught up. Whose story should I tell? For each chapter, I used a simple rule often taught in writing classes: Who has the most to lose?

Science fiction not only shows us what is possible, it critiques the world as it is. Which of the book’s themes are most meaningful to you?

I wrote the book with one question that I tried to test on every page: Will the colony survive? To do that, I considered all the ways the colony could fail—and the ways it could succeed. The question also led to a cascade of other questions. What is worth sacrificing for survival? Can ethics and cooperation be a source of survival? What different kinds of dangers come from outside and inside of a community?

To tell a story, questions have to be dramatized. A person (or a plant with a personality) has to face those dilemmas in their lives. Tatiana hated her role [as commissioner of public peace], but she knew how valuable it was; secrets separated her from others, but she had to keep the secrets and sacrifice her happiness for the good of the community. Stevland, who desperately needed community, found it with beings who were very different from himself, and he could not survive without them; both he and they shared aspirations, and that led him to make ethical choices and strive for cooperation.

Although these questions take place in a novel set on another planet far in the future, we face the same questions ourselves, and fiction lets us focus our thoughts and explore different answers.

Do you view Semiosis as a hopeful, optimistic work?

The colonists arrived with high ideals. They hoped for “joy, love, beauty, community, and life.” It took several generations; they had to face hardship and danger; and they came close to failure. Still, in the end, they achieved their goal.

I believe that people can achieve grand goals. Longwood Gardens is guided by a few key principles that have turned it into an outstanding institution. In Chicago, where I live, from the moment of the city’s founding, the lakefront has been considered a public treasure to remain open and accessible, and the result has been beautiful parkland that stretches for miles.

Ambitious plans can act as magic to stir our blood and lead to amazing achievements. The book, despite its conflicts and violence, is hopeful and optimistic, and so am I.

A compelling part of Semiosis is hearing the “voices” and thoughts of plants. What would plants on Earth say to us?

Survive. That’s what I think the majority of plants would say not just to us but to the animal kingdom in general. Many plants depend on us to care for them, pollinate their flowers, spread their seeds, and create environments that let plants thrive. We humans have sometimes done too much to change the environment, and I think that plants would point this out forcefully if they could, but overall they want us and other species to be there for them now and in the future. A healthy ecology needs all of us.

What is an amazing fact you discovered about plants? Do plants have personality? Do you have a special relationship with a plant at home?

I’ve learned that plants experiment a lot to adjust to their environment. Trees can alter their leaves to adapt to changing weather. Plants often produce seeds with tiny genetic differences to see which tweaks will be more successful. As a result, each plant is an individual. We can never be 100% sure of what they will do. I don’t know if that reaches the level of personality, but it makes each plant a new discovery.

I have a favorite plant. My mother died 26 years ago, but I have one of her plants, a Rhipsalis cereuscula or coral cactus, grown from cuttings that my brother sent me last spring.

When my book launched, I got some gifts of “lucky bamboo” because Stevland is called a bamboo in the book. Usually, lucky bamboo is grown in water, but when mine outgrew their containers, I transferred them to soil. … One plant, named “Steve II” by my sister-in-law, came to me as a lovely spiral-bound column of multiple stems. Apparently this plant hated being confined, and once it was in soil, it had the chance to break out of jail. … The result isn’t quite as lovely, so instead I try to appreciate its new look as a wild exploration of freedom.

What does it mean to you that Semiosis was chosen for Longwood Gardens’ Community Read?

It's simply an honor. It’s also a relief. I tried hard to get the science right, and if Longwood Gardens’ staff likes the book, maybe I succeeded. Science fiction gives us the chance to play “what if” games. What if plants could think? With my book, I explored one answer to that question, but many other answers are possible.

For those readers who have explored the world of Pax in Semiosis, what can we expect from your sequel, Interference?

Interference takes a harder look at culture clash within and among species. An anthropological mission from Earth arrives to study the colony, and the mission and its technology upset what had been a stable equilibrium. We also see more of the world of Pax, and Stevland makes a discovery that overturns his deepest beliefs about himself. Readers seem especially fond of Stevland (so am I), and he gets to do things no plant has done before.