Since the days of the Peirce family, a pair of wrought-iron snakes have occupied various locations on the grounds, alternately delighting and startling unsuspecting visitors. As a result, for the last century, young guests at Longwood have been hunting through lawns and planting beds to find those resident snakes. Last spring, it was determined that the original pair of snakes was deteriorating—and it was decided that a new pair would be forged, using time-honored techniques and materials, and then placed in a new location in our Gardens. Now, new generations can enjoy their whimsy, their character, and their story … which we share with you here.

Elegantly posed as though mid-slither, the original snakes reach about six feet in length and more than an inch in diameter. Each made of a little more than 10 pounds of iron, they were shaped at a blacksmith's forge from a piece of iron bar. Their heads are simple and endearing: raised to peek out of the grass, their open mouths are toothless, and their simple eyes are placed in such a way as to seem quite friendly.

Though we don't know why the Peirce family had them made, we can speculate that they might have been used as a sort of scarecrow or perhaps just for a touch of whimsy. When Pierre S. du Pont purchased the land to become Longwood in 1906, he kept the snakes on and took to hiding them in the lawn. A loving—and occasionally mischievous—uncle to many nieces and nephews, he took delight in tucking amusements and surprises all around the house and grounds for them to find. In adulthood, several of his young relatives wrote a memoir about "Uncle Pierre" (Uncle Pierre and the Kids, written by W.W. Laird with contributed memories from several cousins, printed in 1981) and they recalled the snakes and the playful use he found for them: "When the young were too non-compliant on the porch, Uncle Pierre would say, ‘Why don’t you go play with the snakes? Try to bite one. It is safe. I know the snake won’t bite you back.’”

In the years since Pierre du Pont's death, Longwood has worked to preserve his legacy of beauty and conservation throughout our Gardens, and--with these snakes, as one example—a touch of whimsy. Throughout the years, our horticulturists have carefully arranged them within planting beds in the Conservatory or in the Peirce-du Pont House, and the delight of finding them has continued.

This 1975 photo shows the length and curvature of the original iron snakes. Photo by Gottlieb Hampfler.

Much like many of the garden ornaments at Longwood, such as the foo dog sculptures that stand outside of our Topiary Garden, objects at Longwood Gardens are understandably beloved—but can wear over time, as the environmental conditions that make plants grow and thrive can cause erosion, tarnish, and decay for the objects among them. As Longwood’s Object Collections Coordinator on the Archives team, my job is to monitor the condition of our garden ornaments and ensure that they remain in excellent shape. Occasionally, that means that I have to pull things off display for short-term care to ensure that they can return for long-term guest enjoyment.

In the spring of 2023, as part of a collections condition review, our Archives staff worked with the Horticulture team to pull the snakes out of their Peirce-du Pont House Conservatory planting bed for evaluation. To make a more thorough condition assessment, they were removed to archival collections storage.

When we took a careful look at our long, iron friends, we realized that their tails had begun to flake and fray, a condition that allows water to infiltrate and cause further damage to their bodies. Rather than try to fix the snakes and return them to the same risky situation, our team decided to commission a new pair and treat them to withstand moisture before bringing them back to the Gardens.

After inspecting the snakes with our own expert metalsmith Dave Beck, we determined that the originals would have been forged by a blacksmith. In early Chester County, a blacksmith would have been an essential member of the local farming economy, producing iron goods ranging from horseshoes to hinges. For other fine examples of early forge work, try walking around the outside of the Peirce-du Pont House and hunting for the practical and elegant boot scrapers that were installed in the mortar near doors and porches!

We knew we wanted to find a blacksmith who could reproduce the originals faithfully, and we are so glad to have worked with Chester County blacksmith Luke DiBerardinis, who has been creating reproduction ironwork since he was in middle school, in creating a new pair of snakes. To get started, DiBerardinis first came to our storage facility to trace the particular curvature of the original snakes to make a template. Beck then weighed each snake to determine the amount of iron needed for each reproduction, and DiBerardinis got to work—working from a traditional blacksmith’s forge within the shell of an 1850 barn that he restored.

Longwood Senior Fabricator and Mechanic Dave Beck (left) and local blacksmith Luke DiBerardinis work with one of the original iron snakes to make a template for reproduction. Photo by Kelli Stewart.

To make the snakes, DiBerardinis used reclaimed iron bars, repeatedly heating them and using a variety of tools to hold, hit, and thin the metal. Having traced the curvature of the originals onto his forge floor, he used tongs and an anvil to shape the orange-hot iron—heated to around 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit— into replicas of Mr. du Pont’s originals. Each snake’s engaging and simple face emerged as DiBerardinis flattened and tapered the end of the rod with a 1915 mechanical hammer that he had restored. A small punch and hammer created the iron creatures’ endearing eyes and cemented the connection between the original and the new. Though they are babies compared to their predecessors, these new snakes were made with tools and methods as old as iron itself. We are grateful that a blacksmith who has worked so hard to preserve his craft’s traditions could help us preserve a tradition of our own.

Blacksmith Luke DiBerardinis works in his forge, using a mechanical hammer from the early 20th century to shape the head of an iron snake. Photo by Kelli Stewart.

For finer shaping, DiBerardinis uses a hammer and anvil on the heated iron. Photo by Kelli Stewart.

DiBerardinis’ shop is filled with tongs and hammers of varying shapes and sizes, each serving a particular function in a blacksmith’s work. Photo by Kelli Stewart.

With the head shaped, DiBerardinis used a punch to add the eyes, just like those on the original iron snakes. Photo by Kelli Stewart.

After the head is shaped, DiBerardinis bent the body according to the silhouette sketched out on his forge floor, taken from a tracing of our original generation of iron snakes. Here sits the final version, after the neck and head had been heated to achieve the finished posture. Photo by Kelli Stewart.

Once the snakes had been forged, Beck took them to a local powder coater to receive a finish that would protect the new pair of snakes from moisture and other environmental threats. Visually unobtrusive, the matte black finish will ensure that these snakes will be able to live for a very long time in the Gardens without worry. Meanwhile, the original generation were gently cleaned and prepared for display in the library of the Peirce-du Pont House, where they can be appreciated outside of the soil and moisture that was causing their slow decay.

This 1922 photo shows the original iron snakes on the lawn outside of the Peirce-du Pont House, near their new location outside of the Peirce-du Pont House.

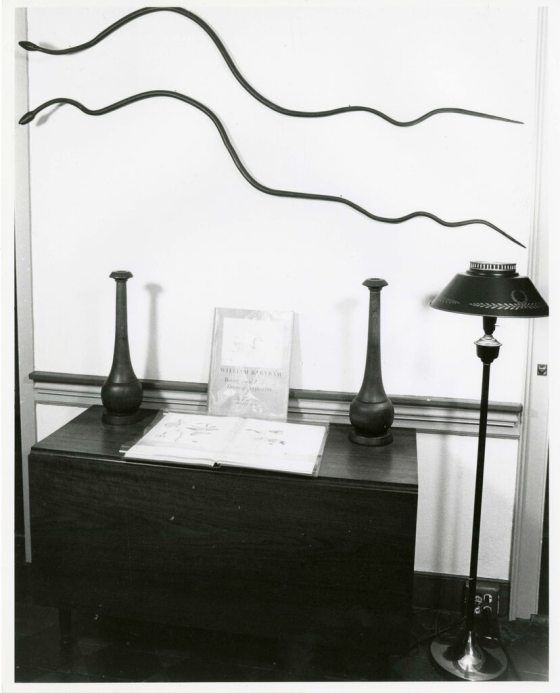

As Mr. du Pont clearly delighted in the snakes’ whimsical presence in the garden, we were excited to place them once more where guests can see their gentle faces and sinuous curves. The original generation have been hung on the wall in the library, safely away from moisture.

This 1979 photo shows how the snakes were previously displayed in an earlier version of the Heritage Exhibit, where guests could view them as part of the Peirce family’s story of life in this place. Photo by Richard Keen.

The original iron snakes, on display now in the Peirce-du Pont House library. Photo by Carol Gross.

The new snakes are on display now outside of the Peirce-du Pont House. Photo by Carol Gross.

For years to come, these garden creatures will delight guests and nod to Mr. du Pont’s much-beloved sense of fun.