Plant conservation has become one of the core responsibilities of public gardens worldwide. This common focus requires gardens to curate, collect, and conserve both globally and locally rare species as an ex situ, or off-site, measure to protect them from exploitation and extinction. At Longwood, we have developed an orchid conservation program that addresses the science, research, and curation of locally, nationally, and globally rare species. Along with local partners, one of our latest efforts under that conservation program is the restoration of the pink lady’s slipper orchid found in the Wissahickon Valley. Representative of the genus Cypripedium, the lady’s slipper is among the most charismatic, well-known, and beloved of all native orchids in Pennsylvania … and among the most threatened.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, populations of all 50 to 60 Cypripedium species worldwide are in decline, with some nearly extinct. Five different Cypripedium species were found in Pennsylvania in early colonial times. At least one of these, C. candidum, or the small white lady’s slipper, was known only from a single, now destroyed site. C. candidum is now considered extirpated, or extinct, in Pennsylvania, but still survives in other states. Happily, some Cypripedium species can still be found in our state. Favoring habitats where the soil is strongly acidic (pH<4.5) and are free of competition from neighboring plants, the pink lady’s slipper, Cypripedium acaule, is the most widespread and commonly encountered lady’s slipper in the Eastern US and Pennsylvania.

The pink lady’s slipper has become rare in the greater Philadelphia area, but was once more common, as herbarium specimens at the Morris Arboretum and Drexel Academy of Sciences indicate. A story titled A Natural Time Machine published in Grid Magazine in January 2019 highlighted the importance of digitizing herbarium specimens to give better access to plant diversity information, including those which have become rare or extirpated in given regions. To highlight this example, authors from the Morris Arboretum and Drexel Academy of Sciences used an herbarium specimen of pink lady’s slipper collected in the Wissahickon Valley Park by famous Philadelphia botanist Dr. E.T. Wherry as an attractive example of a plant that was once known in a heavily populated area that had become extirpated.

After publishing the article, a handful of citizen scientists that frequent the Wissahickon reported an extant, or still surviving, population of the remaining three pink lady’s slipper plants. This report resulted in a rapid exchange of communications and excitement, which led to the creation of a project to hand-pollinate the remaining pink lady’s slipper plants, collect some of the seeds, and propagate them in the tissue culture lab at Longwood Gardens … all with the hope of augmenting the existing population and restoring this species in a wider area of the Wissahickon Valley.

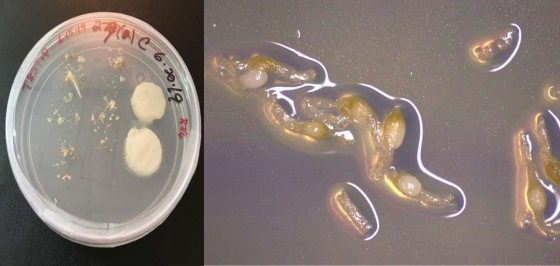

In April 2019 we hand-pollinated the flowers and three resulting seed capsules formed. We collected the seed capsules in June 2019 and entered propagation in the tissue culture lab at the Gardens. We now have 78 seedlings growing in test tubes that await acclimatization to the nursery and ultimately planting back in the wild. This is a long-term project, as seed germination and seedling development takes 18 months in the lab, followed by at least one year in the nursery. Our goal is to plant the first seedlings in fall 2021.

But there’s more to this story. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, pink lady’s slipper is a species of “least concern” and doesn’t fit into their prioritization scheme for protecting plants. Given this categorization, if pink lady’s slipper is listed as a species of least concern in PA and there are so many rare species to work on, the question is why are we making the effort to help conserve and restore this species?

The answer lies in many reasons. Despite its abundance in nature, pink lady’s slipper is a rare species in public and private gardens due to its obligate requirement for strongly acidic, “sterile” soils that can support the growth of only a few associated species. Anecdotal reports from associated literature mentions growers cultivating the pink lady’s slipper in containers and watering with a weak solution of vinegar to keep the pH down. While there may be some truth to these anecdotal reports, that approach to keeping the pH down is an avenue rife with opportunities for experimentation. We are therefore designing an experiment to test the best methods for maintaining low pH while the seedlings are growing under nursery conditions.

Making the effort to help conserve and restore the pink lady’s slipper also allows us to test a previously developed, highly successful in-house propagation protocol used for other native, but rarer, Cypripedium species. Our efforts will allow us to widen the range of species we are working with and collect data, so that we can create a generalized propagation protocol for the genus that others interested in propagating rare Cypripedium species, both in the US and worldwide, can use and adapt.

Perhaps the most important aspect of its project, and the one that has amazed me the most, is that it has brought people together from various groups under a common goal. Several partners, including The Morris Arboretum, Garden Clubs of America, and the Springside Chestnut Hill Academy, are all involved and are playing different, essential roles in the project.

One of the most exciting components of this project is the opportunity to, in the future, work with the Garden Clubs of America and Springside Chestnut Hill Academy to set up experimental restoration plots on their property bordering the Wissahickon Valley. These restoration plots can be used to teach students of all ages the fundamentals of applied plant conservation and restoration. Even though a well-known native species serves as the model for the work, the tools they can learn could be applied to some of the rarest known plant species in the world and will hopefully inspire urgent conservation action in future generations. Until then, we’ll be sure to share updates on the project in future blog posts.