Someone told me something when I first started growing flowers: “the plants tell on you.” Years later and today as one of Longwood’s floriculture managers, that saying has always stuck with me. It means that failing to provide water, nourishment, and a suitable climate for your plants will be reflected in the crop. It may not happen immediately, but the plant will eventually tell on you with evidence becoming apparent over time. This is even more true with a delicate crop like poinsettias, an iconic holiday plant with an interesting history that, despite being notoriously difficult to grow, we’ve woven into many facets of this year’s A Longwood Christmas display, grown in shapes and sizes found nowhere else on Earth.

To greenhouse growers like me, poinsettias, or Euphorbia pulcherrima as they are known scientifically, are much more challenging than most greenhouse crops. They have a particularly high permanent wilting point, or PWP, meaning that they do not bounce back from severe drought. Just one bad day in a grower’s life can mean the end of the crop. Personally, I see this particularity as a challenge, rather than a deterrent, and I’ve never been one to walk away from a challenge.

In its native Mexico, the poinsettia’s prehispanic Nahuatl name, cuetlaxochitl, literally translates to “flower that wilts”. Cultivated in special nurseries in the Aztec highlands, the plants graced Montezuma’s capital city in the 16th century. Although a few 20th century magazine articles mistakenly designated poinsettias as highly poisonous, the white milky fluid exuded after plant tissue injury, known as latex, was used medicinally by the Aztecs. This substance, iconic of the genus, can cause mild skin irritation and is a natural defense against herbivores, so don’t expect your pets or children to try more than a taste. The colored parts of the plant that form at the end of each branch are not actually flowers, but modified leaves called bracts. The poinsettia’s flowers are actually the tiny yellow structures at the center of the colored bracts, called cyathia.

When fully ripe, there is a sweet, sticky substance that oozes from the cyathia that tastes vaguely of honey. When the United States Secretary of War Joel Poinsett went to Mexico as an ambassador in the 1820s, he saw market potential for the plant and had samples sent back to American horticultural institutions, including to Bartram’s Garden in Philadelphia.

Over the ensuing century, the plants became more readily available. They grew particularly well in the hot, dry climate of southern California. This is where, in the early 20th century, the Ecke family established their poinsettia nursery. What made the Ecke poinsettia different from all others was an industry secret for many years. They developed a grafting technique that caused a phytoplasmic infection, the introduction of a bacteria which in some cases could cause plant death or deformation. The result of this particular infection, though, resulted in transforming the leggy, weedy, natural poinsettia of the Mexican forests into a bushier, free-branching plant suitable for American living rooms. This new form was not only significantly more attractive but was also much more durable in a nursery setting, and the Ecke family had a monopoly on the market.

Paul Ecke, Jr. showcased the plant on The Tonight Show and Bob Hope’s Christmas Special in the 1960s and poinsettia sales exploded. The monopoly fell apart in the late 1980s, however, when the secret of the grafting technique was revealed to the rest of the industry. Suddenly, poinsettia breeders all over the world were competing with the Ecke family, creating novel cultivars with a dizzying array of colors and shapes.

Longwood Gardens has benefitted from the work of the Ecke family as well as the proliferation of this knowledge. Each year, we scour the catalogs of the best poinsettia breeders to select around 20 new cultivars to trial, a process we started in 2003. During our poinsettia trials, our production and research teams combine forces in evaluating the new cultivars, deciding which we want to grow in the future.

We are always excited to trial plants with unusual colors or a differently shaped bract. From there, our display designer takes inspiration to create fresh color palettes and plant combinations for our guests to enjoy in our Christmas display. A few plants on display now that were chosen from recent trials include Candy Wintergreen on the southwest walk and Golden Glo on the northeast walk of the Main Conservatory, both examples of some of the new colors coming out in the market.

An interesting color is not enough to make a poinsettia worthy of display at Longwood Gardens, however. While most poinsettias that can be purchased at a garden center are pinched once to promote lateral branching, Longwood’s poinsettias are meticulously trained into a variety of shapes and sizes to fulfill their role in the display. The most common shape for a poinsettia in a bedding crop at Longwood is what we call the “three branch”. To achieve this shape we pinch the apical node, the central top growing tip, after the plant is well established. Once the lateral branches start to grow, we select the three strongest branches and remove the rest. As these three branches grow, we remove side growth and tie the three branches together to form a sort of upside-down pyramidal shape. The resulting triangles are the perfect shape for our display team to fit together to fill a space, create a shape, or build a dramatic sweep of blooms.

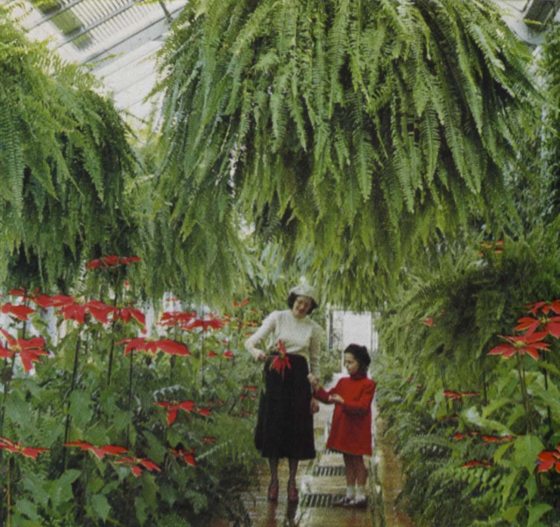

Over the lawn in the Orangery, we have displayed 18 poinsettia baskets with dichondra trailing from the base. Although our display always includes poinsettia baskets, this combination is a Longwood first. We started the plant components in late spring with at least 50 individual plants for each basket, finally bringing the elements together in the middle of July. Each basket takes half a day to build and is then grown hanging in our greenhouses for the following four months. This combination is echoed throughout the Conservatory with dichondra trailing from our window boxes and urns.

Another unique form is the stately and elegant poinsettia standard. Requiring two years of growth and training, these tree-like poinsettias are the result of grafting and very specialized cultivar selection. For the trunk of the standard, we use a very old poinsettia cultivar, one that was bred long before the introduction of the phytoplasmic infection discussed above, that does not branch without intervention. We start these plants in January from cuttings of our own stock plants for display 24 months later. The scion, or top part of the graft, is inserted via T-bud grafting in June, 18 months before display. Common in fruit tree production, T-bud grafts are performed by inserting a small scion bud into a T-shaped slit cut into the outer surface of the stem of the base plant, or rootstock. Successful grafts are carefully pruned and tied to provide proper branching and support. Nutrient needs are monitored closely to achieve optimal growth. Finally, we provide short days with just 10 hours of light by way of blackout curtains beginning in mid-September to make sure the poinsettias are in full-bloom by the time our display opens in mid-November. White forms of these spectacular horticultural feats can be viewed at the central walkway in our Main Conservatory, pink forms flank the doors of our historic Potting Shed, and a few red forms are scattered through other parts of our indoor display.

After years of painstaking care, creative combinations, and meticulous primping, we’re proudly showcasing a wide variety of poinsettia cultivars and more than 4,480 poinsettias in our display, in addition to the 20 new cultivars in our trial. From the huge-bracted Longwood classics Santa Claus Red and Pink to novelty favorites like Winter Rose Early Red, my favorite crop can be found in nearly every space of our Conservatory. Come see these ever-evolving beauties for yourself during A Longwood Christmas, on view now through January 10.