When you look out into Longwood’s natural lands, you may see beautiful, expansive landscapes. Spend a few more minutes looking, and you may observe the layers of a forest or the swales of color and texture of a meadow. Take a couple more moments to look even closer, and you may become aware of the different species that are present, from Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) with their golden plumes of flowers to Mountain mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum) covered with pollinating insects. Natural lands are, by nature, layered and complex. The fields of stewardship and restoration ecology related to natural lands are equally complex—and vital—because we inhabit a world driven by human impact. Where do we—as people—start to heal places negatively impacted by humans? At Longwood, how do we—Longwood’s Land Stewardship and Ecology team—work to address and advance these complex systems of study here at Longwood and beyond?

Here at Longwood, how do we know how do know what areas need help healing versus what places need protecting? How do we know what areas need new plantings or what places need mowing? That is where our Ecological Baseline Study--established by the Land Stewardship and Ecology team under the direction of Associate Director, Land Stewardship and Ecology Lea Johnson—comes in. Part of Longwood’s very own long-term ecological research program, the Ecological Baseline Study began in 2021 with a vegetation study that allows us to see what plant communities make up Longwood’s landscapes, as well as assess the structure and species composition of those communities. It also sets the baseline for analyzing how our plant communities may change in the future.

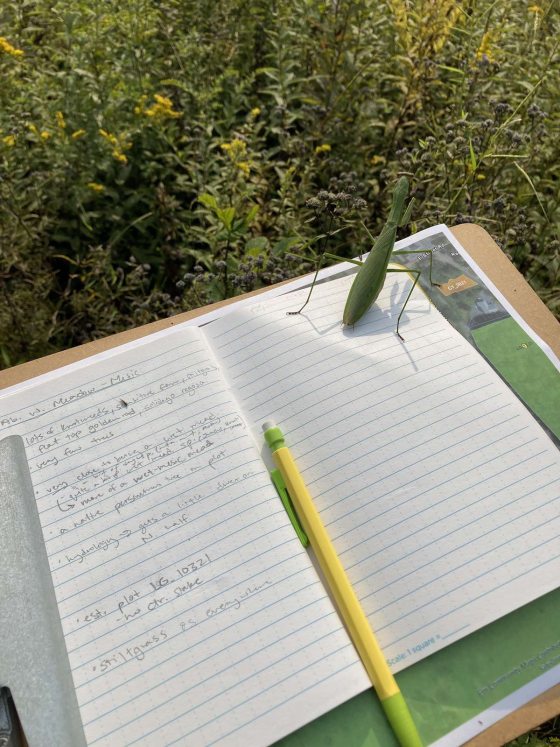

The vegetation baseline study involved many parts, lots of collaboration, and many field days. We mapped all of the plant communities on Longwood’s 750+ acres of natural lands, resulting in the recording of more than 200 plant communities that create a mosaic landscape across Longwood. We sampled the vegetation in more than 50 forests and meadows at Longwood—including measuring the diameter of over 800 trees and identifying hundreds of species—and established these sampling locations as permanent plots that can be monitored for years to come. To accomplish all of this in one year, we partnered with the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program at Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and local botanist Janet Ebert.

Why is all this work for the vegetation baseline study so important? Simply put, we first need to see where we are now to then see, and hopefully direct, where we are going. With the vegetation baseline study and long-term ecological research project, we can track change in our ecosystems to understand how they progress and how stewardship practices help relieve negative impacts on our plant communities. Combined with detailed records of land stewardship practices and tests of different approaches, it will help us answer such questions as: What is the best removal method for Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum)? What is the best mowing regime for our meadows? What planting techniques are best for our forests? The answers to these questions aid our own management and will help us aid the broader community of ecological restoration researchers, stewards, and landowners—as we all shape the land we live on.

As the Land Stewardship and Ecology intern, I was fortunate to be deeply involved with the vegetation baseline study during my internship year here at Longwood. From fieldwork and collaborating with project members, to writing protocols, training team members, managing data, and more, the study has consumed most of my time here … but I am happy to have played a role in laying the foundation of this long-term ecological research project, and helping ensure it continues into the future.

Working in stewardship, it’s hard not to notice environmental stressors, like invasive species, when looking at natural areas—and it’s impossible to ignore their complexities. Each species has its own unique challenges, the research to handle a given situation might not yet exist, and the work itself can be challenging, right down to the strenuous fieldwork that comes with it. So, while I see the beautiful hues of Goldenrod and the plentiful pollinators on mountain mint, I also notice Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) with its choking stems that climb and swarm just about anything and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) with its red stems full of curved thorns that can create ensnaring thickets.

You can see human impacts such as these all over the world. Invasive species such as multiflora rose still invade and dominate areas of natural lands in the Mid-Atlantic. Increasing levels of carbon dioxide and atmospheric temperatures are leading to ocean acidification and coral reef bleaching. Land-use change has made prairies dwindle to exist in less than 1% of their former range in Minnesota (my home state). Most environments can’t escape the impacts of human activity and many of them need human aid to avoid drastic changes like ecosystem regime shifts, desertification, and more. These issues are being caused by human activity and by human action, they can be undone.

While we are excited to see what results and answers may appear through the life of this study, this long-term research program is, as it implies, long and will continue long past my time here at Longwood Gardens. Plant communities and ecosystems develop and change over much longer time scales compared to a human’s life. So, as I wrap up my year here at Longwood and visit the baseline research plots for the last time, I am happy knowing that many will keep returning there for a very long time.