Our planet thrives on variety at every level, from species and biomes and from genes to habitats. Every living thing on earth exists within an ecosystem, and all play a role in the complex web of life that maintains and enhances the health of our planet, our fellow organisms, and our local environments. For people, biodiversity is intrinsic to the necessities of everyday life—food, shelter, fuel, and medicine—and to our appreciation of the beauty of the natural world. At Longwood Gardens, we manage our natural areas to both promote native species diversity across the landscape and to help our guests create memorable and inspiring experiences discovering the dynamic beauty of our native habitats.

Because humanity is changing the planet at vast scales with great speed, conserving and restoring our wild places is more important than ever. Although rapid ecosystem change has brought a loss of biodiversity, with this impact comes the opportunity to research, understand, and reverse habitat loss. Longwood’s Land Stewardship and Ecology program adaptively manages the diverse natural lands that surround our formal gardens. We work to conserve and restore biodiversity, including safeguarding rare Pennsylvania native species and preserving and restoring a wide array of different kinds of habitats.

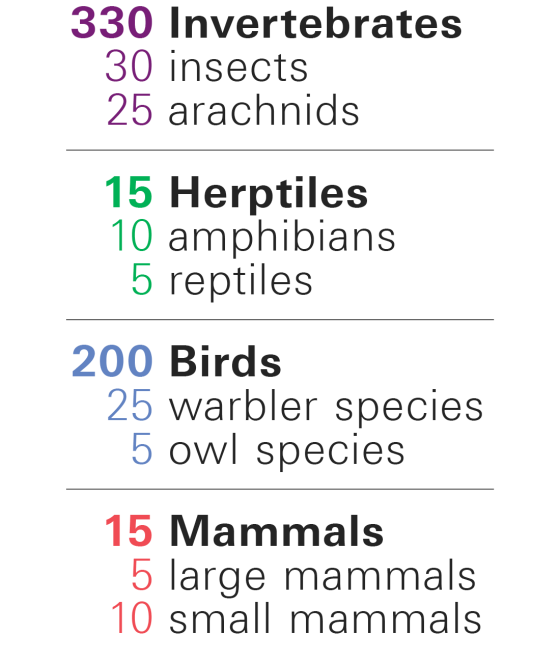

Our guests help us to study how the diversity of Longwood’s wildlife reflects the diversity of our habitats—forests, meadows, streams, and wetlands. Guests at Longwood help us to observe the wild variety of creatures in our formal gardens and natural areas by contributing observations using the iNaturalist and eBird apps, bringing together a global community of scientists and community observers. The species counted above were observed by guests and staff using iNaturalist and eBird. These numbers reflect recent observations, rather than a complete census. We have embarked on an Ecological Baseline Study that will give a more complete picture of our animal life in years to come.

At Longwood, our meadows, streams, wetlands, and forests are home to innumerable invertebrates, birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. We can see red foxes in the meadow, benthic macroinvertebrates like dragonflies in the streams, great blue herons in the wetlands, pileated woodpeckers in the forests, and so much more.

Longwood’s formal gardens also support wildlife—especially pollinators. Our lush displays of flowering plants across the entire growing season offer nectar and pollen resources to an array of butterflies, moths, bees, and hummingbirds. Below, take a look at some of the wildlife we’ve spotted throughout our formal Gardens and our natural lands.

The mice and voles in our meadows provide food for red foxes—small, agile carnivores that belong to the same family as the dog, coyote, and wolf. They are adaptable to many different habitats, including cities and towns. Red foxes are uniquely comfortable around people, though they are rarely seen due to their nocturnal nature. Photo by Hank Davis.

Large wading birds, great blue herons can be seen in our wetlands, as they are commonly spotted near shores of open water and in similar wetlands to ours over most of North and Central America. Photo by Candie Ward.

Native to North America, the insectivore pileated woodpecker inhabits deciduous forests, making our forests at Longwood a perfect place for them to live and breed. Pileated woodpeckers are the third largest species of woodpecker in the world. “Pileated” refers to the bird’s prominent red crest. Photo by Hank Davis.

Long-eared owls can be spotted in our forests, as they are predators for many small mammals such as voles. They may perch on the edge of woodlands and venture out to open ground to hunt for prey. Interestingly, owls do not build their own nests but rather utilize nests built by other animals such as crows. Photo by Hank Davis.

Like other members of the finch family, the American goldfinch has a strong, stout beak for cracking seeds. During the breeding season when males are vibrant yellow, it can be found ranging from mid-Alberta, Canada to North Carolina. American goldfinches then migrate as far south as Mexico in the winter. Males change their bright plumes for an olive color during the winter, while females are generally a yellow-brown shade that brightens in the summer. Social birds, they gather in large flocks while feeding and migrating and prefer open meadows. Goldfinches can often be found in residential areas as they are attracted to bird feeders. Photo by Hank Davis.

Small mammals in the family Leporidae, rabbits can be found throughout our natural areas, and they feed on grass and leafy plants. Photo by Duane Erdmann.

The spicebush swallowtail (Papilio troilus) derives its name from its most common host plant, the spicebush—a native forest shrub with leaves that smell deliciously spicy when rubbed. The species is unique in many ways; it belongs to the family Papilionidae, swallowtails, which include some of the largest butterflies in the world, and unlike other swallowtails, spicebush swallowtails fly low to the ground. Most insects are specialists—they rely on a single species, family, or small group of plants for their survival. Spicebush swallowtails are a great example of an organism that depends on a certain species to live, and that rely on biodiversity of the land. Photo by Hank Davis.

Next time you’re here in our Gardens and see wildlife, know that you can be a part of our observation efforts. You can contribute observations to iNaturalist and eBird—applications linking observers all over the world to the scientific community. About 700 people have collectively contributed nearly 1,600 observations to our research using these community science platforms, helping us to gain a deeper understanding of the lands we steward and the creatures that inhabit them.

Editor’s note: This fall, our Meadow Garden may look a little different than it typically does this time of year. As part of the extraordinary effort to ensure the safety of our community, we mowed part of our Meadow Garden to aid in the search for an escaped prisoner in September. The western and central sections of the Meadow Garden were mowed. Although mowing in this season is a dramatic ecological disturbance, species that live in meadows are resilient. Many of our native meadow plants are perennials that will sprout again from the roots, and the soil has a rich seedbank waiting to germinate when the moment is right.

Our wildlife is also resilient, and we are grateful the eastern portion of the Meadow remains untouched to help serve habitat needs. Happily, we can expect to see the entire Meadow lush with life again in spring.