Humanity has spent millennia perfecting the art of shaping natural systems to our needs. Reassembling the complex webs of interconnection that make up ecosystems, however, is a much newer practice—and for the curious mind, a frontier for discovery. The practice of land stewardship constantly raises new questions—how best to approach a new problem; what methods work best—that can be answered using the tools of ecological science. The answers we get from research feed right back into our management … which always leads to new questions. Our new, experimental forest restoration study, for one, uses a surplus material we have in our Gardens to test methods for building forest soils, suppressing invasive plants, and achieving rapid canopy closure—all while rigorously testing these stewardship techniques and evaluating their long-term effectiveness for conserving and restoring biodiversity.

The Land Stewardship and Ecology team, part of Longwood’s Science Division, is a team of land stewards and researchers who work to cultivate inspiring natural beauty and manage our natural areas using the best and most current ecological science. We integrate research in ecology—the branch of biological science that studies interactions between organisms and the environment—and adaptive land management for beauty and biodiversity. We have an excellent laboratory for this work: nearly 750 acres of forests, fields, wetlands, streams, and meadows surrounding our formal gardens. A portion of one such forested area north of our Meadow Garden is the site for our new experimental forest restoration study.

Everywhere that forest is the dominant regional vegetation, reforestation is a powerful tool for restoring health to streams and landscapes. In the Mid-Atlantic states, remaining and regenerating forests are often small and isolated. These forest patches can be connected and expanded to increase habitat for native forest biodiversity. In many cases, the land between forest patches has been mowed, hayed, plowed, or otherwise used for many decades, resulting in soils very different from the organically carbon-rich ones that forests build over time as wood decays. We are using both advanced technologies like geospatial analysis and shovels-full of dirt to improve the health of our forests.

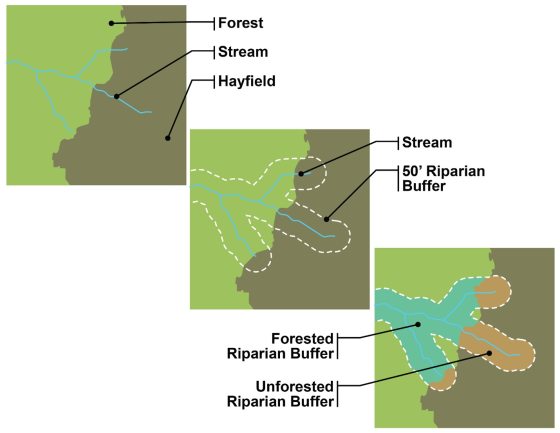

An example of how we use Geographic Information Systems for land stewardship planning. By analyzing spatial ecological data, we can make decisions about future management of the landscape. Because we have mapped our streams and forested plant communities, we can easily identify areas within riparian zones to prioritize for reforestation to improve stream health.

In a forested area north of the Meadow Garden, we have taken a surplus material—woodchips, from Longwood’s arborists—and spread it in a thick layer over the ground to test whether we can accelerate formation of forest soils in reforestation areas. Over time, the woodchips will decompose and be colonized by mycelium—underground fungal networks that are important to forest health. The woodchips are also doing double duty by smothering invasive plants, hopefully reducing the work required to ensure the young trees aren’t engulfed by weeds. In the fall of 2022, we planted fast-growing and clonal trees among the woodchips—adding value with a test of methods to quickly close the forest canopy and shade out competition—again with the aim of reducing maintenance effort. Over the coming years, we will be studying the growth of these trees and the effort spent on maintenance as compared to trees planted in untreated areas.

A future forest waiting to be planted. These young trees belong to species that grow into different shapes and at different speeds. Together they will help to test ways to speed up establishment of newly planted forests. Photo by Lea Johnson.

Land Stewardship and Ecology Research Specialists Kristie Lane Anderson and Tabitha Petri go over the planting plan for the Soils and Succession Forest Restoration Study, which tests techniques for rapid reforestation. Photo by Lea Johnson.

Trees waiting for planting to begin. These trees are being planted into soils that have been treated with woodchips to manage invasive plants and to help speed the formation of forest soil conditions. Photo by Lea Johnson.

One of the great benefits of conducting research at a long-lived, forward-looking institution is the opportunity to study processes that take time to unfold. Many ecological processes develop over the course of years, decades, or even centuries—quite a long time for human observers. Long-term ecological research is key to getting a deeper understanding of how ecosystems respond to change, from global climate and regional urbanization to site-scale streambank reforestation.

Caption: Land Stewardship and Ecology Intern Ellen Oordt uses a laser hypsometer to measure the outer boundaries of a plot for the Baseline Vegetation Study. As our 2022-2023 year-long intern, Oordt has contributed to multiple scientific studies. Photo by Lea Johnson.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution to today’s environmental challenges. With that in mind, we test innovative practices that are relevant to land-managing organizations of different sizes and resource bases—evaluating costs, benefits, and effectiveness of different techniques for conserving and restoring biodiversity, while focusing on habitats and species of concern at local to global scales. Those tests range from our Ecological Baseline Study—which began in 2021 as a way to document the condition of Longwood’s natural areas as a benchmark from which we can measure change—to the 10-year Microstegium Control Study we initiated in 2021 to compare techniques for managing Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), a common invasive species in forest systems.

Land Stewardship and Ecology volunteers hand-pull stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) in one of the treatment plots as part of the Microstegium Management Study. This research will reveal the relative costs and benefits of multiple approaches for managing an introduced grass that smothers the forest floor. Longwood volunteers multiply what our research team can do, contributing hundreds of hours of biodiversity observations each year. Photo by Joe Thomas.

Associate Director, Land Stewardship and Ecology Lea Johnson, Ph.D., is shown kicking off the Ecological Baseline Study on its first day in 2021. Photo by Becca Mathias.

As time goes on, the data we collect will give us a picture of how the landscape is changing over time in response to both our efforts and broader-scale forces of change. Across all of our studies and efforts, we engage in long-term ecological research to understand ecosystem responses to our work and to broader environmental changes that affect our local systems—and other ecosystems like them. All of this fuels our planning, decision-making, and hands-on management, and taking a scientific approach ensures that the work we do contributes to knowledge that others can use to conserve and restore biodiversity near and far.